Cramer's paradox

In mathematics, Cramer's paradox or the Cramer–Euler paradox[1] is the statement that the number of points of intersection of two higher-order curves in the plane can be greater than the number of arbitrary points that are usually needed to define one such curve.

It is named after the Genevan mathematician Gabriel Cramer.

This phenomenon appears paradoxical because the points of intersection fail to uniquely define any curve (they belong to at least two different curves) despite their large number.

It is the result of a naive understanding or a misapplication of two theorems: For all

[4] It has become known as Cramer's paradox after featuring in his 1750 book Introduction à l'analyse des lignes courbes algébriques, although Cramer quoted Maclaurin as the source of the statement.

[5] At about the same time, Euler published examples showing a cubic curve which was not uniquely defined by 9 points[4][6] and discussed the problem in his book Introductio in analysin infinitorum.

The result was publicized by James Stirling and explained by Julius Plücker.

[1] For first-order curves (that is, lines) the paradox does not occur, because

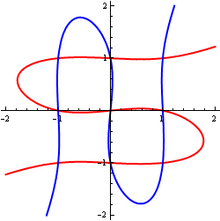

Two nondegenerate conics intersect in at most at four finite points in the real plane, which is precisely the number given as a maximum by Bézout's theorem.

However, five points are needed to define a nondegenerate conic, so again in this case there is no paradox.

In a letter to Euler, Cramer pointed out that the cubic curves

[citation needed] The first equation defines three vertical lines

Hence nine points are not sufficient to uniquely determine a cubic curve in degenerate cases such as these.

But if this determinant is zero, the system is degenerate and the points can be on more than one curve of degree n.