Dynamics (music)

The execution of dynamics also extends beyond loudness to include changes in timbre and sometimes tempo rubato.

Used effectively, dynamics help musicians sustain variety and interest in a musical performance, and communicate a particular emotional state or feeling.

Similarly, in multi-part music, some voices will naturally be played louder than others, for instance, to emphasize the melody and the bass line, even if a whole passage is marked at one dynamic level.

[7] The following notation indicates music starting moderately strong, then becoming gradually stronger and then gradually quieter: Hairpins are typically positioned below the staff (or between the two staves in a grand staff), though they may appear above, especially in vocal music or when a single performer plays multiple melody lines.

("suddenly soft") implies a quick, almost abrupt reduction in volume to around the p range, often employed to subvert listener expectations, signaling a more intimate expression.

[9] Messa di voce is a singing technique and musical ornament on a single pitch while executing a crescendo and diminuendo.

Generally, these markings are supported by the orchestration of the work, with heavy forte passages brought to life by having many loud instruments like brass and percussion playing at once.

However, much of the use of dynamics in early Baroque music remained implicit and was achieved through a practice called raddoppio ("doubling") and later ripieno ("filling"), which consisted of creating a contrast between a small number of elements and then a larger number of elements (usually in a ratio of 2:1 or more) to increase the mass of sound.

In 1752, Johann Joachim Quantz wrote that "Light and shade must be constantly introduced ... by the incessant interchange of loud and soft.

In the Romantic period, composers greatly expanded the vocabulary for describing dynamic changes in their scores.

Where Haydn and Mozart specified six levels (pp to ff), Beethoven used also ppp and fff (the latter less frequently), and Brahms used a range of terms to describe the dynamics he wanted.

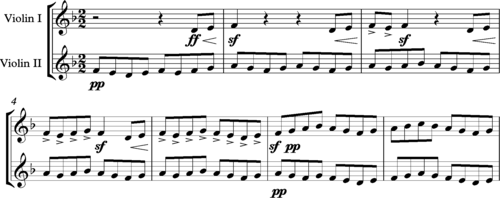

An example of how effective contrasting dynamics can be may be found in the overture to Smetana’s opera The Bartered Bride.

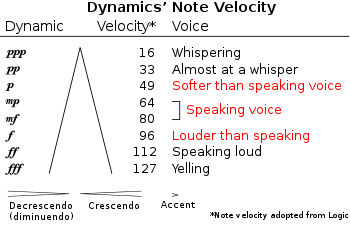

The fast scurrying quavers played pianissimo by the second violins form a sharply differentiated background to the incisive thematic statement played fortissimo by the firsts.In some music notation programs, there are default MIDI key velocity values associated with these indications, but more sophisticated programs allow users to change these as needed.

The introduction of modern recording techniques has provided alternative ways to control the dynamics of music.