Criccieth Castle

The outer curtain wall, the inner ward buildings, and the castle's other three towers are significantly more ruinous, and in places survive only as foundations.

The castle was captured by Edward I of England in 1283 during his conquest of Wales and afterwards repaired and improved, work which included heightening the towers and inner gatehouse.

The castle was besieged in 1294–1295 during an unsuccessful revolt against English rule by Madog ap Llywelyn, and further repairs took place under Edward II in the early fourteenth century.

The only other castle site near Criccieth is a motte at Dolbenmaen, approximately 4 miles (6.4 km) north of the town, which may have been built by the Normans in the eleventh century but was soon occupied by the Welsh.

If this is the case then the fires took place not long after 1450, as there are no further references to the castle being used as a fortress and no record of constables being appointed after Glyndŵr's sacking.

Some parts of the site may have been covered deliberately, as the north tower contained "modern" bricks and china and there was a local tradition that it was infilled in the nineteenth century to prevent children playing in the remains.

[26]An early attempt to date the castle by observing its fabric was made by the antiquarian Thomas Pennant in his 1784 Tour in Wales.

The above-ground fabric was obscured by ivy, modern restoration, and a cairn, and much of the outer ward and the south-east tower were buried.

This made it difficult to ascertain the date and original plan of the castle, particularly that of the outer ward — for example, Hughes speculates that what is now identified as the south-east tower may have been a gateway.

[28] When Criccieth was placed in state care in 1933 extensive archaeological excavations were begun, under the direction of Bryan O'Neil, and continued until shortly after the outbreak of World War II.

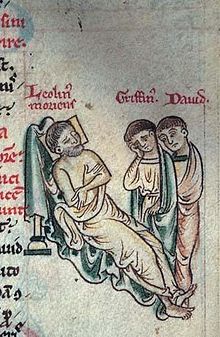

[29] During this time the buried portions of the castle were uncovered and many objects were recovered; a significant find was a crucifix made of gilt bronze and Limoges enamel, found in the western inner gatehouse tower and now in the collection of Amgueddfa Cymru.

[31] O'Neil's identification of three building phases is widely accepted, and together with the excavations forms the basis of the contemporary understanding of the castle.

[33] For his part, in 1983 Avent thought it likely that the north tower was English work, but by 1989 considered Llywelyn ab Iorwerth to be the more probable builder.

There is consensus that Beeston Castle in Cheshire was the primary source, a theory supported by archaeologists including Richard Avent, Laurence Keen, and Rachel Swallow.

Beeston was built in the 1220s by Ranulf de Blondeville, an ally of Llywelyn ap Iorwerth,[c] and is broadly similar to Criccieth.

It was built on a crag and its inner gatehouse consists of two D-shaped towers, each containing a chamber with two arrowloops facing the approach, and a gate passage guarded by a portcullis and a pair of doors.

There are differences: Criccieth has three arrowloops to each guardroom, had a stone–vaulted gate passage rather than a wooden ceiling, and its towers were longer and similar to apsidal keeps.

[37] Whatever the exact inspiration for the gatehouse, the result, according to Avent, is that at Criccieth "the latest advances in military technology" are combined with the "somewhat haphazard Welsh castle building style".

The inner ward forms an irregular six-sided enclosure and contains a twin-towered gatehouse on the north side and a tower on the south-east.

The outer ward is roughly triangular, following the shape of the headland, and contains towers in the north and south-west corners and a modest gatehouse in the south-east.

The third phase is probably part of the repairs undertaken by Edward II; it heightened the gatehouse again, blocking the second-phase battlements and creating new ones above, one of which survives on the eastern tower.

The rear wall may also have contained fireplaces, as fragments of late thirteenth- or early fourteenth-century chimney were also found during excavations.

Four chutes in the adjoining section of curtain wall to the north are part of the original construction, and served latrines at ground and first-floor level.

The wall-walk survives on the southern and western stretches, as well as the parapet and half an embrasure where the wall meets the west gatehouse tower.

Little trace remains of the buildings which stood against the wall, but footings and beam-holes indicate that they existed, as does a 1292 reference to the "king's hall".

In the south-east corner, adjacent to the tower, is the south gate, a simple opening which originally served as a postern and later as a means of communication between the two wards.

A flight of wide, shallow steps was built against the inner wall by Edward I, and running south-west from their base is a cobbled platform.

Shortly afterward a second gate was added at the outer end of the passage and its eastern wall thickened, which necessitated lengthening the embrasure on this side.