Crimean Khanate

The territory controlled by the Crimean Khanate shifted throughout its existence due to the constant incursions by the Cossacks, who had lived along the Don since the disintegration of the Golden Horde in the 15th century.

[17][page needed] In the 11th century, Cumans (Kipchaks) appeared in Crimea; they later became the ruling and state-forming people of the Golden Horde and the Crimean Khanate.

The rulers of the Golden Horde repeatedly organized punitive campaigns in the Crimea when the local population refused to pay tribute.

Grand Duke of Lithuania Algirdas broke the Tatar army in 1363 near the mouth of the Dnieper, and then invaded the Crimea, devastated Chersonesos and seized valuable church objects there.

[29] In the sources of the 16th–18th centuries, the opinion according to which the separation of the Crimean Tatar state was raised to Tokhtamysh, and Canike was the most important figure in this process, completely prevailed.

[30] The Crimean Khanate originated in the early 15th century when certain clans of the Golden Horde Empire ceased their nomadic life in the Desht-i Kipchak (Kypchak Steppes of today's Ukraine and southern Russia) and decided to make Crimea their yurt (homeland).

At that time, the Golden Horde of the Mongol Empire had governed the Crimean peninsula as an ulus since 1239, with its capital at Qirim (Staryi Krym).

But Hacı Giray then had to fight off internal rivals before he could ascend the throne of the khanate in 1449, after which he moved its capital to Qırq Yer (today part of Bahçeseray).

[31] The khanate included the Crimean Peninsula (except the south and southwest coast and ports, controlled by the Republic of Genoa & Trebizond Empire) as well as the adjacent steppe.

"[32] In 1475 the Ottoman forces, under the command of Gedik Ahmet Pasha, conquered the Greek Principality of Theodoro and the Genoese colonies at Cembalo, Soldaia, and Caffa (modern Feodosiya).

[37][38] The Crimeans frequently mounted raids into the Danubian principalities, Poland–Lithuania, and Muscovy to enslave people whom they could capture; for each captive, the khan received a fixed share (savğa) of 10% or 20%.

The assistance of İslâm III Giray during the Khmelnytsky Uprising in 1648 contributed greatly to the initial momentum of military successes for the Cossacks.

[44] The relationship with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was also exclusive, as it was the home dynasty of the Girays, who sought sanctuary in Lithuania in the 15th century before establishing themselves on the Crimean peninsula.

A successful campaign by Devlet I Giray upon the Russian capital in 1571 culminated in the burning of Moscow, and he thereby gained the sobriquet, That Alğan (seizer of the throne).

[49] Several conflicts occurred between Circassians and Crimean Tatars in the 18th century, with the former defeating an army of Khan Kaplan Giray and Ottoman auxiliaries in the battle of Kanzhal.

[50] The Turkish traveler writer Evliya Çelebi mentions the impact of Cossack raids from Azak upon the territories of the Crimean Khanate.

[51] The decline of the Crimean Khanate was a consequence of the weakening of the Ottoman Empire and a change in Eastern Europe's balance of power favouring its neighbours.

Without sufficient guns, the Tatar cavalry suffered a significant loss against European and Russian armies with modern equipment.

The era of great slave raids in Russia and Ukraine was over, although brigands and Nogay raiders continued their attacks, and consequently Russian hatred of the Crimean Khanate did not decrease.

These politico-economic losses led in turn to erosion of the khan's support among noble clans, and internal conflicts for power ensued.

Circassians (Atteghei) and Cossacks also occasionally played roles in Crimean politics, alternating their allegiance between the khan and the beys.

Another Muslim official, appointed not by the clergy but the Ottoman sultan, was the kadıasker, the overseer of the khanate's judicial districts, each under jurisdiction of a kadi.

[53] Mikhail Kizilov writes: "According to Marcin Broniewski (1578), the Tatars seldom cultivated the soil themselves, with most of their land tilled by the Polish, Ruthenian, Russian, and Walachian (Moldavian) slaves.

Crimean law granted them special financial and political rights as a reward, according to local folklore, for historic services rendered to an uluhane (first wife of a Khan).

Crimea had important trading ports where the goods arrived via the Silk Road were exported to the Ottoman Empire and Europe.

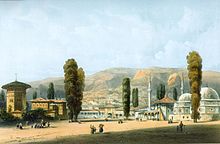

Crimean Khanate had many large cities such as the capital Bahçeseray, Kezlev (Yevpatoria), Qarasu Bazar (Market on black water) and Aqmescit (White-mosque) having numerous hans (caravansarais and merchant quarters), tanners, and mills.

Bahçeseray kilims (oriental rugs) were exported to Poland, and knives made by Crimean Tatar artisans were deemed the best by the Caucasian tribes.

The slave trade (15th–17th century) of captured Ukrainians and Russians was one of the major sources of income for Crimean Tartar and Nogai nobility.

[57] The Selim II Giray fountain, built in 1747, is considered one of the masterpieces of Crimean Khanate's hydraulic engineering designs and is still marveled in modern times.

It consists of small ceramic pipes, boxed in an underground stone tunnel, stretching back to the spring source more than 20 metres (66 feet) away.