Criminal-justice financial obligations in the United States

[1] CJFOs consist of fines, property forfeiture, costs, fees, and victim restitution, and may also include payment for child support.

The United States Supreme Court has generally held the measure to be constitutional, ruling that debtors may be imprisoned for willful non-payment.

Failure to repay CJFOs may result in a number of negative consequences, including accruing interest and penalties; imprisonment; extension of court ordered supervision; negative impacts on credit score; diminished access to housing, transportation and employment; ineligibility for public assistance; and ineligibility to vote, possess a firearm, be pardoned, or request deferred prosecution.

This practice may have played a significant role in early emigration to the US, as debtors comprised almost two thirds of Europeans in the Thirteen Colonies.

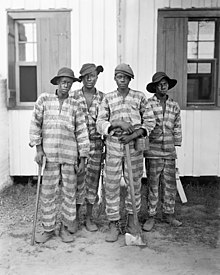

"Charged with fees and fines several times their annual earnings, many southern prisoners were leased by justice officials to corporations who paid their fees in exchange for inmates’ labor in coal and steel mines and on railroads, quarries, and farm plantations," which in turn helped to fund the judiciary and law enforcement.

This was in part due to the exponential increase of people in the criminal justice system's jails, courts, prisons, and probation and parole departments.

To avoid the associated increase in costs to taxpayers, legislators instead shifted part of that burden to those within the system by imposing new fees, fines, and surcharges, as well as enacting proactive strategies to collect those debts.

[2]: 20 Throughout this era, multiple US court cases addressed the issue of CJFOs, and the financial status of the accused or convicted, especially as it related to incarceration: The result of these and other rulings is that courts can sentence individuals to incarceration for nonpayment of CJFOs, so long as they hold a hearing and make a determination that the failure to pay was willful, there was a lack of bona fide effort to do so, and alternative means of punishment are insufficient to meet the state's interest in justice.

[16] According to analysis by Gleicher and Delong with the Center for Justice Research and Evaluation, "[t]his creates a cumulative disadvantage that further entrenches vulnerable people into a cycle of poverty and incarceration.

[1] Despite the ruling in Bearden v. Georgia, courts often interpret "willful" failure to pay in such a way that they require defendants, even those who may be homeless, "to go to great lengths to secure the means for payment, including seeking loans from friends, family members, and employers, or taking day-laborer jobs.

"[7] In many cases, failure to pay CJFOs may disqualify the individual from receiving public assistance, and debts that are incurred through the justice system are not subject to discharge through bankruptcy.

[9] Until payment is complete, legal debtors may be ineligible to vote, possess a firearm, be pardoned, or request deferred prosecution.