Criticism of the war on terror

The notion of a "war" against "terrorism" has proven highly contentious, with critics charging that participating governments exploited it to pursue long-standing policy/military objectives,[1] reduce civil liberties,[2] and infringe upon human rights.

With a military presence in Iraq and Afghanistan, and its associated collateral damage, Shirley Williams posits that this increases resentment and terrorist threats against the West.

[4] Other criticism include United States hypocrisy,[5] media induced hysteria,[6] and that changes in American foreign and security policy have shifted world opinion against the US.

Others merely rely on the instinct of most people when confronted with an act that involves innocent civilians being killed or maimed by men armed with explosives, firearms or other weapons.

[10]Former U.S. President George W. Bush articulated the goals of the war on terror in a September 20, 2001 speech, in which he said that it "will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated.

Excerpts from an April 2006 report compiled from sixteen U.S. government intelligence agencies, however, has strengthened the claim that engaging in Iraq has increased terrorism in the region.

[citation needed] Richard N. Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, argues that on the eve of U.S. intervention in 2003, Iraq represented, at best, a gathering threat and not an imminent one.

"[14] However, Haass argues that U.S. intervention in Afghanistan in 2001 began as a war of necessity—vital interests were at stake—but morphed "into something else and it crossed a line in March 2009, when President Barack Obama decided to sharply increase American troop levels and declared that it was U.S. policy to 'take the fight to the Taliban in the south and east' of the country."

[21] Richard Jackson notes how countries like Russia, India, Israel and China also adopted the language of the war on terror to describe their own fight against domestic insurgents and dissidents.

He argues that "Linking rebels and dissidents at home to the global 'war on terrorism' gives these governments both the freedom to crack down on them without fear of international condemnation, and in some cases, direct military assistance from America".

University of Chicago professor and political scientist, Robert Pape has written extensive work on suicide terrorism and states that it is triggered by military occupations, not extremist ideologies.

"[34] The United Kingdom ambassador to Italy, Ivor Roberts, echoed this criticism when he stated that President Bush was "the best recruiting sergeant ever for al Qaeda.

[5][39]In the months leading up to the invasion of Iraq, President Bush and members of his administration indicated they possessed information which demonstrated a link between Saddam Hussein and al-Qaeda.The consensus among intelligence experts is that these claims were false and that there was never an operational relationship between the two.

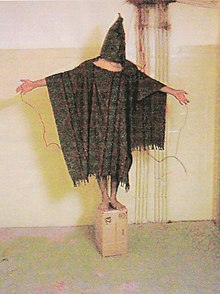

[46] There has also been politically motivated systematic cover-ups of war crimes of American soldiers participating in campaign operations across the world; with the knowledge of their military superiors.

The report's author Stephanie Savell stated that in an ideal scenario, the preferable way of quantifying the total death toll would've been by studying excess mortality, or by using on-the-ground researchers in the affected countries.

Theologian Lawrence Davidson, who studies contemporary Muslims societies in North America, defines this concept as a stereotyping of all followers of Islam as real or potential terrorists due to alleged hateful and violent teaching of their religion.

"[54] This line of argument echoes Edward Said’s famous piece Orientalism in which he argued that the United States sees the Muslims and Arabs in essentialized caricatures – as oil supplies or potential terrorists.

[55] Assistant Professor at Leiden University Tahir Abbas has criticised the war for resulting in the "securitisation of Muslims" and the spread of Islamophobic discourses internationally since 2001.

[56] During decades of post 9/11 hysteria, Muslims have been subject to widespread demonization in the Western mass-media, characterised by racist stereotypes and intense securitization.

Hollywood movies and TV shows have portrayed simplistic depictions of Arab characters and advanced dualistic notions that have been causing the promulgation of Islamophobic stereotypes in the society.

[58][59][60][61] In 2002, strong majorities supported the U.S.-led war on terror in Britain, France, Germany, Japan, India and Russia, according to a sample survey conducted by the Pew Research Center.

[62] Marek Obrtel, a former lieutenant colonel and military doctor in the Army of the Czech Republic, publicly returned his medals earned in NATO operations in 2014.

[66][67][68] American pollster Andrew Kohut, while speaking to the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs, noted that and according to the Pew Research Center polls conducted in 2004, "the ongoing conflict in Iraq continues to fuel anti-American sentiments.

[71][72] Researchers in communication studies and political science found that American understanding of the "war on terror" is directly shaped by how mainstream news media reports events associated with the conflict.

"Framing is a process whereby communicators, consciously or unconsciously, act to construct a point of view that encourages the facts of a given situation to be interpreted by others in a particular manner," wrote Kuypers.

In his book, Trapped in the War on Terror[6] political scientist Ian S. Lustick claimed, "The media have given constant attention to possible terrorist-initiated catastrophes and to the failures and weaknesses of the government's response."

Cooper found that bloggers specializing in criticism of media coverage advanced four key points: David Barstow won the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting for connecting the Department of Defense to over 75 retired generals supporting the Iraq War on television and radio networks.

He added that a "culture of legislative restraint" was needed in passing anti-terrorism laws and that a "primary purpose" of the violent attacks was to tempt countries such as Britain to "abandon our values."

He stated that in the eyes of the UK criminal justice system, the response to terrorism had to be "proportionate and grounded in due process and the rule of law": London is not a battlefield.

[78][79] Nigel Lawson, former Chancellor of the Exchequer, called for Britain to end its involvement in the War in Afghanistan, describing the mission as "wholly unsuccessful and indeed counter-productive.