Spinning mule

Modern versions are still in production and are used to spin woollen yarns from noble fibres such as cashmere, ultra-fine merino and alpaca for the knitted textile market.

The invention by John Kay of the flying shuttle made the loom twice as productive, causing the demand for cotton yarn to vastly exceed what traditional spinners could supply.

Businessmen such as Richard Arkwright employed inventors to find solutions that would increase the amount of yarn spun, then took out the relevant patents.

This produced thread suitable for warp, but the multiple rollers required much more energy input and demanded that the device be driven by a water wheel.

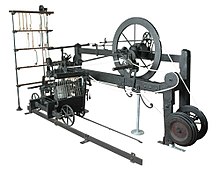

The spinning mule has a fixed frame with a creel of cylindrical bobbins to hold the roving, connected through the headstock to a parallel carriage with the spindles.

Henry Stones, a mechanic from Horwich, constructed a mule using toothed gearing and, importantly, metal rollers.

[7] Baker of Bury worked on drums,[9] and Hargreaves used parallel scrolling to achieve smoother acceleration and deceleration.

McConnell & Kennedy ventured into spinning when they were left with two unpaid-for mules;[12] their firm prospered and eventually merged into the Fine Spinners & Doublers Association.

[13] William Eaton, in 1818, improved the winding of the thread by using two faller wires and performing a backing off at the end of the outward traverse.

[16] Bolton specialised in fine count cotton, and its mules ran more slowly to put in the extra twist.

[17] Spinning wool is a different process as the variable lengths of the individual fibres means that they are unsuitable for attenuation by roller drafting.

[18] Condenser spinning was developed to enable the short fibres produced as waste from the combing of fine cottons, to be spun into a soft, coarse yarns suitable for sheeting, blankets etc.

In Italy for example by Bigagli [2] and Cormatex [3] Mule spindles rest on a carriage that travels on a track a distance of 60 inches (1.5 m), while drawing out and spinning the yarn.

On the return trip, known as putting up,[20] as the carriage moves back to its original position, the newly spun yarn is wound onto the spindle in the form of a cone-shaped cop.

As the mule spindle travels on its carriage, the roving which it spins is fed to it through rollers geared to revolve at different speeds to draw out the yarn.

When the latter are bare, as in a new mule, the spindle-driving motion is put into gear, and the attendants wind upon each spindle a short length of yarn from a cop held in the hand.

The back rollers pull the sliver from the bobbins, and passing it to the succeeding pairs, whose differential speeds attenuate it to the required degree of fineness.

As it is delivered in front, the spindles, revolving at a rate of 6,000–9,000 rpm twist the hitherto loose fibres together, thus forming a thread.

Whilst this is going on, the spindle carriage is being drawn away from the rollers, at a pace very slightly exceeding the rate at which the roving is coming forth.

Should a thick place in the roving come through the rollers, it would resist the efforts of the spindle to twist it; and, if passed in this condition, it would seriously deteriorate the quality of the yarn, and impede subsequent operations.

The carriage, which is borne upon wheels, continues its outward progress, until it reaches the extremity of its traverse, which is 63 inches (160 cm) from the roller beam.

The speed of revolution of the spindle must vary, as the faller is guiding the thread upon the larger or smaller diameter of the cone of the cop.

After the first few draws the minder would stop the mule at the start of an inward run and take it in slowly depressing and releasing the faller wire several times.

Alternatively, a starch paste could be skilfully applied to the first few layers of yarn by the piecers – and later a small paper tube was dropped over spindle – this slowed down the doffing operation and extra payment was negotiated by the minders.

They were specialists in spinning, and were answerable only to the gaffer and under-gaffer who were in charge of the floor and with it the quantity and quality of the yarn that was produced.

Delineation of jobs was rigid and communication would be through the means of coloured slips of paper written on in indelible pencil.

As the bobbin ran empty he would pick it off its skewer in the creel unreeling 30 cm or so of roving, and drop it into a skip.

Home spinning was the occupation of women and girls, but the strength needed to operate a mule caused it to be the activity of men.

[27] It replaced decentralised cottage industries with centralised factory jobs, driving economic upheaval and urbanisation.

The spindles, when running, threw out a mist of oil at crotch height, that was captured by the clothing of anyone piecing an end.