Cross

[1][2][3] Before then, it was used as a religious or cultural symbol throughout Europe, in western and south Asia (the latter, in the form of the original Swastika); and in Egypt, where the Ankh was a hieroglyph that represented "life" and was used in the worship of the god Aten.

The word's history is complicated; it appears to have entered English from Old Irish, possibly via Old Norse, ultimately from the Latin crux (or its accusative crucem and its genitive crucis), "stake, cross".

[7] In the Roman world, furca replaced crux as the name of some cross-like instruments for lethal and temporary punishment,[8][9] ranging from a forked cross to a gibbet or gallows.

Speculation has associated the cross symbol – even in the prehistoric period – with astronomical or cosmological symbology involving "four elements" (Chevalier, 1997) or the cardinal points, or the unity of a vertical axis mundi or celestial pole with the horizontal world (Koch, 1955).

[22] The shape of the cross (crux, stauros "stake, gibbet"), as represented by the Latin letter T, came to be used as a new symbol (seal) or emblem of Christianity since the 2nd century AD to succeeding Ichthys in aftermaths of that new religion's separation from Judaism.

[25] In his book De Corona, written in 204, Tertullian tells how it was already a tradition for Christians to trace repeatedly on their foreheads the sign of the cross.

An early example of the cruciform halo, used to identify Christ in paintings, is found in the Miracles of the Loaves and Fishes mosaic of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna (6th century).

Egyptian hieroglyphs involving cross shapes include ankh "life", ndj "protect" and nfr "good; pleasant, beautiful".

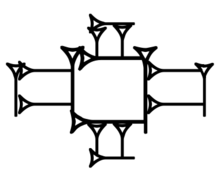

Sumerian cuneiform had a simple cross-shaped character, consisting of a horizontal and a vertical wedge (𒈦), read as maš "tax, yield, interest"; the superposition of two diagonal wedges results in a decussate cross (𒉽), read as pap "first, pre-eminent" (the superposition of these two types of crosses results in the eight-pointed star used as the sign for "sky" or "deity" (𒀭), DINGIR).

The multiplication sign (×), often attributed to William Oughtred (who first used it in an appendix to the 1618 edition of John Napier's Descriptio) apparently had been in occasional use since the mid 16th century.

[29] Other typographical symbols resembling crosses include the dagger or obelus (†), the Chinese (十, Kangxi radical 24) and Roman (X ten).