Crossing number (graph theory)

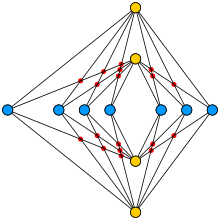

[1] The study of crossing numbers originated in Turán's brick factory problem, in which Pál Turán asked for a factory plan that minimized the number of crossings between tracks connecting brick kilns to storage sites.

Mathematically, this problem can be formalized as asking for the crossing number of a complete bipartite graph.

[2] The same problem arose independently in sociology at approximately the same time, in connection with the construction of sociograms.

Without further qualification, the crossing number allows drawings in which the edges may be represented by arbitrary curves.

No vertex should be mapped onto an edge that it is not an endpoint of, and whenever two edges have curves that intersect (other than at a shared endpoint) their intersections should form a finite set of proper crossings, where the two curves are transverse.

[5] Some authors add more constraints to the definition of a drawing, for instance that each pair of edges have at most one intersection point (a shared endpoint or crossing).

For the crossing number as defined above, these constraints make no difference, because a crossing-minimal drawing cannot have edges with multiple intersection points.

[6] During World War II, Hungarian mathematician Pál Turán was forced to work in a brick factory, pushing wagon loads of bricks from kilns to storage sites.

Mathematically, the kilns and storage sites can be formalized as the vertices of a complete bipartite graph, with the tracks as its edges.

[7] Kazimierz Zarankiewicz attempted to solve Turán's brick factory problem;[8] his proof contained an error, but he established a valid upper bound of for the crossing number of the complete bipartite graph Km,n.

This bound has been conjectured to be the optimal number of crossings for all complete bipartite graphs.

[9] The problem of determining the crossing number of the complete graph was first posed by Anthony Hill, and appeared in print in 1960.

[10] Hill and his collaborator John Ernest were two constructionist artists fascinated by mathematics.

They not only formulated this problem but also originated a conjectural formula for this crossing number, which Richard K. Guy published in 1960.

The conjecture is that there can be no better drawing, so that this formula gives the optimal number of crossings for the complete graphs.

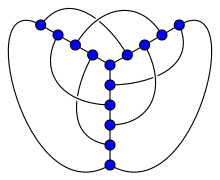

[13] The smallest cubic graphs with crossing numbers 1–11 are known (sequence A110507 in the OEIS).

Specifically, Bhat and Leighton used it (for the first time) for deriving an upper bound on the number of edge crossings in a drawing which is obtained by a divide and conquer approximation algorithm for computing

[19] In general, determining the crossing number of a graph is hard; Garey and Johnson showed in 1983 that it is an NP-hard problem.

[22] A closely related problem, determining the rectilinear crossing number, is complete for the existential theory of the reals.

[23] On the positive side, there are efficient algorithms for determining whether the crossing number is less than a fixed constant k. In other words, the problem is fixed-parameter tractable.

on graphs of bounded degree[26] which use the general and previously developed framework of Bhat and Leighton.

These algorithms are used in the Rectilinear Crossing Number distributed computing project.

[27] For an undirected simple graph G with n vertices and e edges such that e > 7n the crossing number is always at least This relation between edges, vertices, and the crossing number was discovered independently by Ajtai, Chvátal, Newborn, and Szemerédi,[28] and by Leighton .

[28][18] The motivation of Leighton in studying crossing numbers was for applications to VLSI design in theoretical computer science.

[31] If edges are required to be drawn as straight line segments, rather than arbitrary curves, then some graphs need more crossings.