Cryptanalysis of the Enigma

In December 1932 it was broken by mathematician Marian Rejewski at the Polish General Staff's Cipher Bureau,[5] using mathematical permutation group theory combined with French-supplied intelligence material obtained from a German spy.

Five weeks before the outbreak of World War II, in late July 1939 at a conference just south of Warsaw, the Polish Cipher Bureau shared its Enigma-breaking techniques and technology with the French and British.

During the German invasion of Poland, core Polish Cipher Bureau personnel were evacuated via Romania to France, where they established the PC Bruno signals intelligence station with French facilities support.

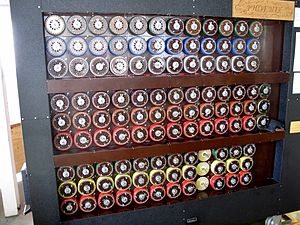

Alan Turing, a Cambridge University mathematician and logician, provided much of the original thinking that led to upgrading of the Polish cryptologic bomb used in decrypting German Enigma ciphers.

During World War I, inventors in several countries realised that a purely random key sequence, containing no repetitive pattern, would, in principle, make a polyalphabetic substitution cipher unbreakable.

Comparing the possible plaintext Keine besonderen Ereignisse (literally, "no special occurrences"—perhaps better translated as "nothing to report"; a phrase regularly used by one German outpost in North Africa), with a section of ciphertext, might produce the following: The red cells represent these clashes.

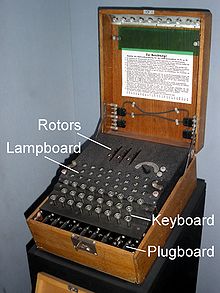

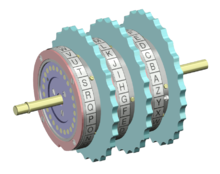

The mechanism of the Enigma consisted of a keyboard connected to a battery and a current entry plate or wheel (German: Eintrittswalze), at the right hand end of the scrambler (usually via a plugboard in the military versions).

Although a leading British cryptographer, Dilly Knox (a veteran of World War I and the cryptanalytical activities of the Royal Navy's Room 40), worked on decipherment he had only the messages he generated himself to practice with.

The material enabled Rejewski to achieve "one of the most important breakthroughs in cryptologic history"[46] by using the theory of permutations and groups to work out the Enigma scrambler wiring.

[57] However, on 1 November 1937, the Germans changed the Enigma reflector, necessitating the production of a new catalogue—"a task which [says Rejewski] consumed, on account of our greater experience, probably somewhat less than a year's time".

[76] In August, two Polish Enigma doubles were sent to Paris, whence Gustave Bertrand took one to London, handing it to Stewart Menzies of Britain's Secret Intelligence Service at Victoria Station.

By the time the Cipher Bureau was ordered to cross the border into allied Romania on 17 September, they had destroyed all sensitive documents and equipment and were down to a single very crowded truck.

Britain's Government Code and Cipher School (GC&CS), before its move to Bletchley Park, had realised the value of recruiting mathematicians and logicians to work in codebreaking teams.

Alan Turing, a Cambridge University mathematician with an interest in cryptology and in machines for implementing logical operations—and who was regarded by many as a genius—had started work for GC&CS on a part-time basis from about the time of the Munich Crisis in 1938.

Bletchley Park maintained detailed indexes[110] of message preambles, of every person, of every ship, of every unit, of every weapon, of every technical term, and of repeated phrases such as forms of address and other German military jargon.

One German agent in Britain, Nathalie Sergueiew, code-named Treasure, who had been 'turned' to work for the Allies, was very verbose in her messages back to Germany, which were then re-transmitted on the Abwehr Enigma network.

Harold "Doc" Keen of the British Tabulating Machine Company (BTM) in Letchworth (35 kilometres (22 mi) from Bletchley) was the engineer who turned Turing's ideas into a working machine—under the codename CANTAB.

The other plugboard connections and the settings of the alphabet rings would then be worked out before the scrambler positions at the possible true stops were tried out on Typex machines that had been adapted to mimic Enigmas.

[136] Although the German army, SS, police, and railway all used Enigma with similar procedures, it was the Luftwaffe (Air Force) that was the first and most fruitful source of Ultra intelligence during the war.

[138] Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring was known to use it for trivial communications, including informing squadron commanders to make sure the pilots he was going to decorate had been properly deloused.

Collecting a set of enciphered message keys for a particular day allowed cycles (or boxes as Knox called them) to be assembled in a similar way to the method used by the Poles in the 1930s.

When this was cancelled, Birch told Fleming that "Turing and Twinn came to me like undertakers cheated of a nice corpse..."[152] A major advance came through Operation Claymore, a commando raid on the Lofoten Islands on 4 March 1941.

This was the Kurzsignale (short signals), a code which the German navy used to minimise the duration of transmissions, thereby reducing the risk of being located by high-frequency direction finding techniques.

The Royal Navy's victory at the Battle of Cape Matapan in March 1941 was considerably helped by Ultra intelligence obtained from Italian naval Enigma signals.

Colonel John Tiltman, who later became Deputy Director at Bletchley Park, visited the US Navy cryptanalysis office (OP-20-G) in April 1942 and recognised America's vital interest in deciphering U-boat traffic.

Commander Edward Travis, Deputy Director and Frank Birch, Head of the German Naval Section travelled from Bletchley Park to Washington in September 1942.

[168] It established a relationship of "full collaboration" between Bletchley Park and OP-20-G.[169] An all electronic solution to the problem of a fast bombe was considered,[170] but rejected for pragmatic reasons, and a contract was let with the National Cash Register Corporation (NCR) in Dayton, Ohio.

[171] Alan Turing, who had written a memorandum to OP-20-G (probably in 1941),[172] was seconded to the British Joint Staff Mission in Washington in December 1942, because of his exceptionally wide knowledge about the bombes and the methods of their use.

The Admiralty specifically did not target the tanker Gedania and the scout Gonzenheim, figuring that sinking so many ships within one week would indicate to Germany that Britain was reading Enigma.

[192] When Abwehr personnel who had worked on Fish cryptography and Russian traffic were interned at Rosenheim around May 1945, they were not at all surprised that Enigma had been broken,[citation needed][dubious – discuss] only that someone had mustered all the resources in time to actually do it.