The Crystal Palace

It has been suggested that the name of the building resulted from a piece penned by the playwright Douglas Jerrold, who in July 1850 wrote in the satirical magazine Punch about the forthcoming Great Exhibition, referring to a "palace of very crystal".

The huge, modular, iron, wood and glass,[5] structure was originally erected in Hyde Park in London to house the Great Exhibition of 1851, which showcased the products of many countries throughout the world.

[7] Within three weeks, the committee had received some 245 entries, including 38 international submissions from Australia, the Netherlands, Belgium, Hanover, Switzerland, Brunswick, Hamburg and France.

Two designs, both in iron and glass, were singled out for praise—one by Richard Turner, co-designer of the Palm House, Kew Gardens, and the other by French architect Hector Horeau[8] but despite the great number of submissions, the committee rejected them all.

At this point, renowned gardener Joseph Paxton became interested in the project, and with the enthusiastic backing of commission member Henry Cole, he decided to submit his own design.

The "Great Stove" (or conservatory) at Chatsworth (built in 1836) was the first major application of his ridge-and-furrow roof design and was at the time the largest glass building in the world, covering around 28,000 square feet (2,600 m2).

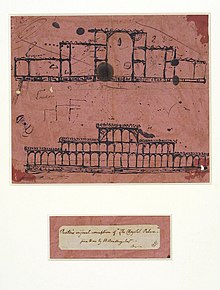

Two days later on 11 June, while attending a board meeting of the Midland Railway, Paxton made his original concept drawing, which he doodled onto a sheet of pink blotting paper.

This rough sketch (now in the Victoria and Albert Museum) incorporated all the basic features of the finished building, and it is a mark of Paxton's ingenuity and industriousness that detailed plans, calculations and costings were ready to submit in less than two weeks.

Impressed by the low bid for the construction contract submitted by the civil engineering contractor Fox, Henderson and Co, the commission accepted the scheme and gave its public endorsement to Paxton's design in July 1850.

It incorporated many breakthroughs, offered practical advantages that no conventional building of that era could match and, above all, it embodied the spirit of British innovation and industrial might that the Great Exhibition was intended to celebrate.

[17] Because the entire building was scaled around those dimensions, it meant that nearly the whole outer surface could be glazed using hundreds of thousands of identical panes, thereby drastically reducing both their production cost and the time needed to install them.

The basic roofing unit, in essence, took the form of a long triangular prism, which made it both extremely light and very strong, and meant it could be built with the minimum amount of materials.

Like the Chatsworth Lily House (but different to its later incarnation at Sydenham Hill), most of the roof of the original Hyde Park structure had a horizontal profile, so heavy rain posed a potentially serious safety hazard.

To maintain a comfortable temperature inside such a large glass building was another major challenge, because the Great Exhibition took place decades before the introduction of electricity and air-conditioning.

These served multiple functions: they reduced heat transmission, moderated and softened the light coming into the building, and acted as a primitive evaporative cooling system when water was sprayed onto them.

Each of the modules that formed the outer walls of the building was fitted with a prefabricated set of louvres that could be opened and closed using a gear mechanism, allowing hot stale air to escape.

[20] The floor too had a dual function: the gaps between the boards acted as a grating that allowed dust and small pieces of refuse to fall or be swept through them onto the ground beneath, where it was collected daily by a team of cleaning boys.

These consisted of two strong poles which were set several meters apart at the base and then lashed together at the top to form a triangle; this was stabilized and kept vertical by guy ropes fixed to the apex, stretched taut and tied to stakes driven into the ground some distance away.

For the glazing, Paxton used larger versions of machines he had originally devised for the Great Stove at Chatsworth, installing on-site production line systems, powered by steam engines, that dressed and finished the building parts.

When completed, the Crystal Palace provided an unrivalled space for exhibits, since it was essentially a self-supporting shell standing on slim iron columns, with no internal structural walls whatsoever.

It is often suggested that the euphemism "spending a penny" originated at the exhibition,[31][32] but the phrase is more likely to date from the 1890s when public lavatories, fitted with penny-coin-operated locks, were first established by British local authorities.

Dozens of experts such as Matthew Digby Wyatt and Owen Jones were hired to create a series of courts that provided a narrative of the history of fine art.

The daily "Programme for Monday October 6th (1873)" included a harvest exhibition of fruit, and the Australasian Collection, formed by H E Pain, of materials from Tasmania, New Caledonia, Solomon Islands, Australia and New Zealand; and a grand military fete was also on offer.

A few years later, the Imperial War Museum moved to South Kensington, and then in the 1930s to its present site Geraldine Mary Harmsworth Park, formerly Bethlem Royal Hospital.

[57] Robert Windsor-Clive, 1st Earl of Plymouth bought it for £230,000 (equivalent to £29,585,782 in 2023) to save it from the developers with the understanding that a fund raised by the Lord Mayor of London would reimburse him.

[61] The fire spread quickly in the high winds that night, in part because of the dry old timber flooring, and the huge quantity of flammable materials in the building.

The south tower to the right of the Crystal Palace entrance was taken down shortly after the fire, as the damage sustained had undermined its integrity and presented a major risk to houses nearby.

[76] The Bowl has been inactive as a music venue for several years, and the stage has fallen into a state of disrepair, but as of March 2020 London Borough of Bromley Council are working with a local action group to find "creative and community-minded business proposals to reactivate the cherished concert platform".

Plans by the London Development Agency to spend £67.5 million to refurbish the site, including new homes and a regional sports centre were approved after Public Inquiry in December 2010.

In 2013, the Chinese company ZhongRong Holdings held early talks with the London Borough of Bromley and Mayor Boris Johnson to rebuild the Crystal Palace on the north side of the park.