Crystal oscillator

Quartz crystals are also found inside test and measurement equipment, such as counters, signal generators, and oscilloscopes.

The first crystal-controlled oscillator, using a crystal of Rochelle salt, was built in 1917 and patented[6] in 1918 by Alexander M. Nicholson at Bell Telephone Laboratories, although his priority was disputed by Walter Guyton Cady.

Using the early work at Bell Laboratories, American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T) eventually established their Frequency Control Products division, later spun off and known today as Vectron International.

Shortages of crystals during the war caused by the demand for accurate frequency control of military and naval radios and radars spurred postwar research into culturing synthetic quartz, and by 1950 a hydrothermal process for growing quartz crystals on a commercial scale was developed at Bell Laboratories.

In 1968, Juergen Staudte invented a photolithographic process for manufacturing quartz crystal oscillators while working at North American Aviation (now Rockwell) that allowed them to be made small enough for portable products like watches.

A crystal is a solid in which the constituent atoms, molecules, or ions are packed in a regularly ordered, repeating pattern extending in all three spatial dimensions.

The result is that a quartz crystal behaves like an RLC circuit, composed of an inductor, capacitor and resistor, with a precise resonant frequency.

Quartz has the further advantage that its elastic constants and its size change in such a way that the frequency dependence on temperature can be very low.

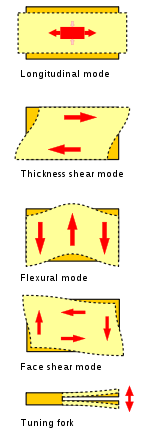

The specific characteristics depend on the mode of vibration and the angle at which the quartz is cut (relative to its crystallographic axes).

A quartz crystal can be modeled as an electrical network with low-impedance (series) and high-impedance (parallel) resonance points spaced closely together.

During startup, the controlling circuit places the crystal into an unstable equilibrium, and due to the positive feedback in the system, any tiny fraction of noise is amplified, ramping up the oscillation.

But, like many other mechanical resonators, crystals exhibit several modes of oscillation, usually at approximately odd integer multiples of the fundamental frequency.

Due to aging and environmental factors (such as temperature and vibration), it is difficult to keep even the best quartz oscillators within one part in 1010 of their nominal frequency without constant adjustment.

Acceleration effects including gravity are also reduced with SC-cut crystals, as is frequency change with time due to long term mounting stress variation.

[24] The SiO4 tetrahedrons form parallel helices; the direction of twist of the helix determines the left- or right-hand orientation.

Crystals for AT-cut are the most common in mass production of oscillator materials; the shape and dimensions are optimized for high yield of the required wafers.

Crystals for SAW devices are grown as flat, with large X-size seed with low etch channel density.

The impurities have a negative impact on radiation hardness, susceptibility to twinning, filter loss, and long and short term stability of the crystals.

The composition of the growth solution, whether it is based on lithium or sodium alkali compounds, determines the charge compensating ions for the aluminium defects.

Germanium impurities tend to trap electrons created during irradiation; the alkali metal cations then migrate towards the negatively charged center and form a stabilizing complex.

The composition of the crystal can be gradually altered by outgassing, diffusion of atoms of impurities or migrating from the electrodes, or the lattice can be damaged by radiation.

Silver and aluminium are often used as electrodes; however both form oxide layers with time that increases the crystal mass and lowers frequency.

A DC voltage bias between the electrodes can accelerate the initial aging, probably by induced diffusion of impurities through the crystal.

Failures may be, however, introduced by faults in bonding, leaky enclosures, corrosion, frequency shift by aging, breaking the crystal by too high mechanical shock, or radiation-induced damage when non-swept quartz is used.

[69] The low frequency cuts are mounted at the nodes where they are virtually motionless; thin wires are attached at such points on each side between the crystal and the leads.

The large mass of the crystal suspended on the thin wires makes the assembly sensitive to mechanical shocks and vibrations.

[52] The crystals are usually mounted in hermetically sealed glass or metal cases, filled with a dry and inert atmosphere, usually vacuum, nitrogen, or helium.

E.g. the BVA resonator (Boîtier à Vieillissement Amélioré, Enclosure with Improved Aging),[70][unreliable source?]

developed in 1976; the parts that influence the vibrations are machined from a single crystal (which reduces the mounting stress), and the electrodes are deposited not on the resonator itself but on the inner sides of two condenser discs made of adjacent slices of the quartz from the same bar, forming a three-layer sandwich with no stress between the electrodes and the vibrating element.

The gap between the electrodes and the resonator act as two small series capacitors, making the crystal less sensitive to circuit influences.