Crystal skull

Crystal skulls are human skull hardstone carvings made of clear, milky white or other types of quartz (also called "rock crystal"), claimed to be pre-Columbian Mesoamerican artifacts by their alleged finders; however, these claims have been refuted for all of the specimens made available for scientific studies.

The results of these studies demonstrated that those examined were manufactured in the mid-19th century or later, almost certainly in Europe, during a time when interest in ancient culture abounded.

[2][4] Despite some claims presented in an assortment of popularizing literature, legends of crystal skulls with mystical powers do not figure in genuine Mesoamerican or other Native American mythologies and spiritual accounts.

Crystal skulls have been a popular subject appearing in numerous science fiction television series, novels, films, and video games.

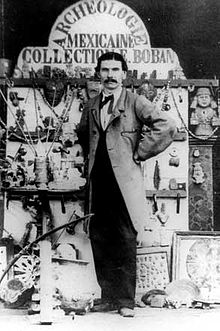

[4] It has been established that the crystal skulls in the British Museum and Paris's Musée de l'Homme[10] were originally sold by the French antiquities dealer Eugène Boban, who was operating in Mexico City between 1860 and 1880.

According to the Smithsonian, Boban acquired his crystal skulls from sources in Germany, aligning with conclusions made by the British Museum.

The Smithsonian specimen had been worked with a different abrasive, namely silicon carbide (carborundum), a silicon-carbon compound which is a synthetic substance manufactured using modern industrial techniques.

[18] The British Museum catalogues the skull's provenance as "probably European, 19th century AD"[17] and describes it as "not an authentic pre-Columbian artefact".

[22] It was examined and described by Smithsonian researchers as "very nearly a replica of the British Museum skull – almost exactly the same shape, but with more detailed modeling of the eyes and the teeth".

[23] Mitchell-Hedges claimed that she found the skull buried under a collapsed altar inside a temple in Lubaantun, in British Honduras, now Belize.

In the early 1970s it came under the temporary care of freelance art restorer Frank Dorland, who claimed upon inspecting it that it had been "carved" with total disregard to the natural crystal axis, and without the use of metal tools.

Garvin made arrangements for the skull to be examined at Hewlett-Packard's crystal laboratories in Santa Clara, California, where it was subjected to several tests.

[31] As well as the traces of mechanical grinding on the teeth noted by Dorland,[32] Mayanist archaeologist Norman Hammond reported that the holes (presumed to be intended for support pegs) showed signs of being made by drilling with metal.

[34] The earliest published reference to the skull is the July 1936 issue of the British anthropological journal Man, where it is described as being in the possession of Sydney Burney, a London art dealer who was said to have owned it since 1933,[35] and from whom evidence suggests F.A.

[40] In November 2007, Homann took the skull to the office of anthropologist Jane MacLaren Walsh, in the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History for examination.

After a series of analyses carried out over three months, C2RMF engineers concluded that it was "certainly not pre-Columbian, it shows traces of polishing and abrasion by modern tools".

Anna Mitchell-Hedges claimed that the skull she allegedly discovered could cause visions and cure cancer, that she once used its magical properties to kill a man, and that in another instance, she saw in it a premonition of the John F. Kennedy assassination.

[48] In the 1931 play The Satin Slipper by Paul Claudel, King Philip II of Spain uses "a death's head made from a single piece of rock crystal", lit by "a ray of the setting sun", to see the defeat of the Spanish Armada in its attack on the Kingdom of England.

Interviewees included Richard Hoagland, who attempted to link the skulls and the Maya to life on Mars, and David Hatcher Childress, proponent of lost Atlantean civilizations and anti-gravity claims.

The alleged associations and origins of crystal skull mythology in Native American spiritual lore, as advanced by neoshamanic writers such as Jamie Sams, are similarly discounted.

[53] Instead, as Philip Jenkins notes, crystal skull mythology may be traced back to the "baroque legends" initially spread by F.A.