Ctenophora

: ctenophore /ˈtɛnəfɔːr, ˈtiːnə-/ TEN-ə-for, TEE-nə-; from Ancient Greek κτείς (kteis) 'comb' and φέρω (pherō) 'to carry')[6] comprise a phylum of marine invertebrates, commonly known as comb jellies, that inhabit sea waters worldwide.

Despite their soft, gelatinous bodies, fossils thought to represent ctenophores appear in Lagerstätten dating as far back as the early Cambrian, about 525 million years ago.

[9][10] Pisani et al. reanalyzed the data and suggested that the computer algorithms used for analysis were misled by the presence of specific ctenophore genes that were markedly different from those of other species.

[11][12][page needed] Follow up analysis by Whelan et al. (2017)[13] yielded further support for the 'Ctenophora sister' hypothesis; the issue remains a matter of taxonomic dispute.

), ctenophores' bodies consist of a relatively thick, jelly-like mesoglea sandwiched between two epithelia, layers of cells bound by inter-cell connections and by a fibrous basement membrane that they secrete.

In specialized parts of the body, the outer layer also contains colloblasts, found along the surface of tentacles and used in capturing prey, or cells bearing multiple large cilia, for locomotion.

The side furthest from the organ is covered with ciliated cells that circulate water through the canals, punctuated by ciliary rosettes, pores that are surrounded by double whorls of cilia and connect to the mesoglea.

If they enter less dense brackish water, the ciliary rosettes in the body cavity may pump this into the mesoglea to increase its bulk and decrease its density, to avoid sinking.

[45] Monofunctional catalase (CAT), one of the three major families of antioxidant enzymes that target hydrogen peroxide, an important signaling molecule for synaptic and neuronal activity, is also absent, most likely due to gene loss.

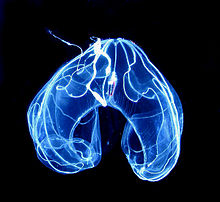

Members of the lobate genera Bathocyroe and Ocyropsis can escape from danger by clapping their lobes, so that the jet of expelled water drives them back very quickly.

[22] The Thalassocalycida, only discovered in 1978 and known from only one species,[59] are medusa-like, with bodies that are shortened in the oral-aboral direction, and short comb-rows on the surface furthest from the mouth, originating from near the aboral pole.

There are two known species, with worldwide distribution in warm, and warm-temperate waters: Cestum veneris ("Venus' girdle") is among the largest ctenophores – up to 1.5 meters (4.9 ft) long, and can undulate slowly or quite rapidly.

[22] Platyctenids are usually cryptically colored, live on rocks, algae, or the body surfaces of other invertebrates, and are often revealed by their long tentacles with many side branches, seen streaming off the back of the ctenophore into the current.

Adults of most species can regenerate tissues that are damaged or removed,[61] although only platyctenids reproduce by cloning, splitting off from the edges of their flat bodies fragments that develop into new individuals.

[66][67] In Mnemiopsis leidyi, nitric oxide (NO) signaling is present both in adult tissues and differentially expressed in later embryonic stages suggesting the involvement of NO in developmental mechanisms.

[72] When some species, including Bathyctena chuni, Euplokamis stationis and Eurhamphaea vexilligera, are disturbed, they produce secretions (ink) that luminesce at much the same wavelengths as their bodies.

Detailed statistical investigation has not suggested the function of ctenophores' bioluminescence nor produced any correlation between its exact color and any aspect of the animals' environments, such as depth or whether they live in coastal or mid-ocean waters.

[73] In ctenophores, bioluminescence is caused by the activation of calcium-activated proteins named photoproteins in cells called photocytes, which are often confined to the meridional canals that underlie the eight comb rows.

In bays where they occur in very high numbers, predation by ctenophores may control the populations of small zooplanktonic organisms such as copepods, which might otherwise wipe out the phytoplankton (planktonic plants), which are a vital part of marine food chains.

[79] Ctenophores used to be regarded as "dead ends" in marine food chains because it was thought their low ratio of organic matter to salt and water made them a poor diet for other animals.

[82] Mnemiopsis is well equipped to invade new territories (although this was not predicted until after it so successfully colonized the Black Sea), as it can breed very rapidly and tolerate a wide range of water temperatures and salinities.

[84] Mnemiopsis populations in those areas were eventually brought under control by the accidental introduction of the Mnemiopsis-eating North American ctenophore Beroe ovata,[86] and by a cooling of the local climate from 1991 to 1993,[85] which significantly slowed the animal's metabolism.

Claudia Mills estimates that there about 100–150 valid species that are not duplicates, and that at least another 25, mostly deep-sea forms, have been recognized as distinct but not yet analyzed in enough detail to support a formal description and naming.

Despite their fragile, gelatinous bodies, fossils thought to represent ctenophores – apparently with no tentacles but many more comb-rows than modern forms – have been found in Lagerstätten as far back as the early Cambrian, about 515 million years ago.

Three additional putative species were then found in the Burgess Shale and other Canadian rocks of similar age, about 505 million years ago in the mid-Cambrian period.

[3] Evidence from China a year later suggests that such ctenophores were widespread in the Cambrian, but perhaps very different from modern species – for example one fossil's comb-rows were mounted on prominent vanes.

[91] The early Cambrian sessile frond-like fossil Stromatoveris, from China's Chengjiang lagerstätte and dated to about 515 million years ago, is very similar to Vendobionta of the preceding Ediacaran period.

Cestida Since all modern ctenophores except the beroids have cydippid-like larvae, it has widely been assumed that their last common ancestor also resembled cydippids, having an egg-shaped body and a pair of retractable tentacles.

[128] A molecular phylogeny analysis in 2001, using 26 species, including four recently discovered ones, confirmed that the cydippids are not monophyletic and concluded that the last common ancestor of modern ctenophores was cydippid-like.

This suggests that the last common ancestor of modern ctenophores was relatively recent, and perhaps survived the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 65.5 million years ago while other lineages perished.

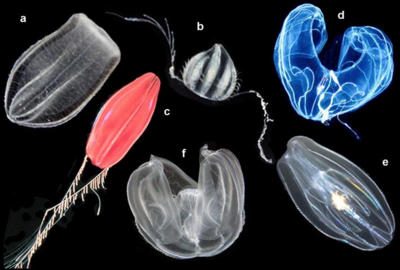

a Beroe ovata , b unidentified cydippid, c "Tortugas red" cydippid,

d Bathocyroe fosteri , e Mnemiopsis leidyi , and f Ocyropsis sp. [ 17 ]