Cube (algebra)

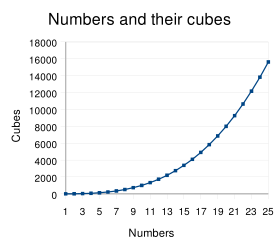

In arithmetic and algebra, the cube of a number n is its third power, that is, the result of multiplying three instances of n together.

The cube of a number n is denoted n3, using a superscript 3,[a] for example 23 = 8.

The cube operation can also be defined for any other mathematical expression, for example (x + 1)3.

The graph of the cube function is known as the cubic parabola.

This happens if and only if the number is a perfect sixth power (in this case 26).

The last digits of each 3rd power are: It is, however, easy to show that most numbers are not perfect cubes because all perfect cubes must have digital root 1, 8 or 9.

Moreover, the digital root of any number's cube can be determined by the remainder the number gives when divided by 3: It is conjectured that every integer (positive or negative) not congruent to ±4 modulo 9 can be written as a sum of three (positive or negative) cubes with infinitely many ways.

Integers congruent to ±4 modulo 9 are excluded because they cannot be written as the sum of three cubes.

In September 2019, the previous smallest such integer with no known 3-cube sum, 42, was found to satisfy this equation:[2] One solution to

The selected solution is the one that is primitive (gcd(x, y, z) = 1), is not of the form

(since they are infinite families of solutions), satisfies 0 ≤ |x| ≤ |y| ≤ |z|, and has minimal values for |z| and |y| (tested in this order).

The equation x3 + y3 = z3 has no non-trivial (i.e. xyz ≠ 0) solutions in integers.

The sum of the first n cubes is the nth triangle number squared: Proofs.

Charles Wheatstone (1854) gives a particularly simple derivation, by expanding each cube in the sum into a set of consecutive odd numbers.

Applying this property, along with another well-known identity: we obtain the following derivation: In the more recent mathematical literature, Stein (1971) uses the rectangle-counting interpretation of these numbers to form a geometric proof of the identity (see also Benjamin, Quinn & Wurtz 2006); he observes that it may also be proved easily (but uninformatively) by induction, and states that Toeplitz (1963) provides "an interesting old Arabic proof".

For example, the sum of the first 5 cubes is the square of the 5th triangular number, A similar result can be given for the sum of the first y odd cubes, but x, y must satisfy the negative Pell equation x2 − 2y2 = −1.

Also, every even perfect number, except the lowest, is the sum of the first 2p−1/2 odd cubes (p = 3, 5, 7, ...): There are examples of cubes of numbers in arithmetic progression whose sum is a cube: with the first one sometimes identified as the mysterious Plato's number.

The formula F for finding the sum of n cubes of numbers in arithmetic progression with common difference d and initial cube a3, is given by A parametric solution to is known for the special case of d = 1, or consecutive cubes, as found by Pagliani in 1829.

[10] In real numbers, the cube function preserves the order: larger numbers have larger cubes.

In other words, cubes (strictly) monotonically increase.

Also, its codomain is the entire real line: the function x ↦ x3 : R → R is a surjection (takes all possible values).

All aforementioned properties pertain also to any higher odd power (x5, x7, ...) of real numbers.

Equalities and inequalities are also true in any ordered ring.

Volumes of similar Euclidean solids are related as cubes of their linear sizes.

Cubes occasionally have the surjective property in other fields, such as in Fp for such prime p that p ≠ 1 (mod 3),[11] but not necessarily: see the counterexample with rationals above.

Determination of the cubes of large numbers was very common in many ancient civilizations.

Mesopotamian mathematicians created cuneiform tablets with tables for calculating cubes and cube roots by the Old Babylonian period (20th to 16th centuries BC).

[12][13] Cubic equations were known to the ancient Greek mathematician Diophantus.

[14] Hero of Alexandria devised a method for calculating cube roots in the 1st century CE.

[15] Methods for solving cubic equations and extracting cube roots appear in The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art, a Chinese mathematical text compiled around the 2nd century BCE and commented on by Liu Hui in the 3rd century CE.