Cucuteni–Trypillia culture

[2][3] The majority of Cucuteni–Trypillia settlements were of small size, high density (spaced 3 to 4 kilometres apart), concentrated mainly in the Siret, Prut and Dniester river valleys.

[4] During its middle phase (c. 4100 to 3500 BC), populations belonging to the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture built some of the largest settlements in Eurasia, some of which contained as many as three thousand structures and were possibly inhabited by 20,000 to 46,000 people.

[11][15] The economy was based on an elaborate agricultural system, along with animal husbandry, with the inhabitants knowing how to grow plants that could withstand the ecological constraints of growth.

Burada and other scholars from Iași, including the poet Nicolae Beldiceanu and archeologists Grigore Butureanu, Dimitrie C. Butculescu and George Diamandy, subsequently began the first excavations at Cucuteni in the spring of 1885.

[3] During the Atlantic and Subboreal climatic periods in which the culture flourished, Europe was at its warmest and moistest since the end of the last Ice Age, creating favorable conditions for agriculture in this region.

Over the course of the fifth millennium, the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture expanded from its 'homeland' in the Prut–Siret region along the eastern foothills of the Carpathian Mountains into the basins and plains of the Dnieper and Southern Bug rivers of central Ukraine.

Much less common than other materials, copper axes and other tools have been discovered that were made from ore mined in Volyn, Ukraine, as well as some deposits along the Dnieper river.

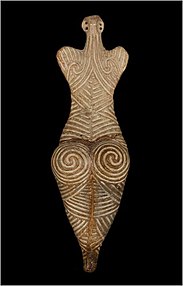

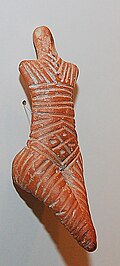

Indeed, it was partially the archaeological evidence from Cucuteni–Trypillia culture that inspired Marija Gimbutas, Joseph Campbell and some latter 20th century feminists to set forth the popular theory of an Old European culture of peaceful, egalitarian (counter to a widespread misconception, "matristic" not matriarchal[38]), goddess-centred neolithic European societies that were wiped out by patriarchal, Sky Father-worshipping, warlike, Bronze-Age Proto-Indo-European tribes that swept out of the steppes north and east of the Black Sea.

[39] In this, "the process of Indo-Europeanization was a cultural, not a physical, transformation and must be understood as a military victory in terms of successfully imposing a new administrative system, language, and religion upon the indigenous groups.

He cites evidence of the refugees having used caves, islands and hilltops (abandoning in the process 600–700 settlements) to argue for the possibility of a gradual transformation rather than an armed onslaught bringing about cultural extinction.

[42] Another potential contradicting indication is that the kurgans that replaced the traditional horizontal graves in the area now contain human remains of a fairly diversified skeletal type approximately ten centimeters taller on average than the previous population.

[4] At the same time, some Eneolithic steppe burials from the northwest Pontic region already displayed rather tall stature hundreds of years before the emergence of the Yamna culture complex.

A conflict with that theoretical possibility is that during the warm Atlantic period, Denmark was occupied by Mesolithic cultures, rather than Neolithic, notwithstanding the climatic evidence.

In between these two economic models (the hunter-gatherer tribes and Bronze Age civilisations) we find the later Neolithic and Eneolithic societies such as the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture, where the first indications of social stratification began to be found.

[3] A recent study by scientists from the Collaborative Research Centre (CRC 1266) at the University of Kiel even showed that, based on the isotopic composition of bones and plants, cattle were intensively pastured to provide manure for the growing of pulses.

They cultivated club wheat, oats, rye, proso millet, barley and hemp, which were probably ground and baked as unleavened bread in clay ovens or on heated stones in the home.

At its peak it was one of the most technologically advanced societies in the world at the time,[4] developing new techniques for ceramic production, housing building, agriculture and producing woven textiles (although these have not survived and are known indirectly).

In terms of overall size, some of Cucuteni–Trypillia sites, such as Talianki (with a population of 15,000 and covering an area of 335[60] hectares) in the province of Uman Raion, Ukraine, are as large as (or perhaps even larger than) the city-states of Sumer in the Fertile Crescent, and these Eastern European settlements predate the Sumerian cities by more than half of a millennium.

A. Diachenko considers these to be climate refugees from Trypillia-settled areas in the northwest,[62] while A. G. Nikitin suggests these were migrants from the Gumelnița-Karanovo VI sites in the west Pontic.

Each house, including its ceramic vases, ovens, figurines and innumerable objects made of perishable materials, shared the same circle of life, and all of the buildings in the settlement were physically linked together as a larger symbolic entity.

An anthropomorphic ceramic artefact was discovered during an archaeological dig in 1942 on Cetatuia Hill near Bodești, Neamț County, Romania, which became known as the "Cucuteni Frumusica Dance" (after a nearby village of the same name).

[76] The following types of tools have been discovered at Cucuteni–Trypillia sites:[citation needed] Some researchers, e.g., Asko Parpola, an Indologist at the University of Helsinki in Finland, believe that the CT-culture used the wheel with wagons.

[33] There have been so many of these figurines discovered in Cucuteni–Trypillia sites[33] that many museums in eastern Europe have a sizeable collection of them, and as a result, they have come to represent one of the more readily identifiable visual markers of this culture to many people.

[33]: 115 Currently, the only Trypillian site where human remains dating to the first half of the 4th millennium BC have been consistently found is Verteba Cave in west Ukraine.

[81] The only definite conclusion that can be drawn from archaeological evidence is that in the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture, in the vast majority of cases, the bodies were not formally deposited within the settlement area.

[82] They analyzed mtDNA recovered from Cucuteni–Trypillia human osteological remains found in the Verteba Cave (on the bank of the Seret River, Ternopil Oblast, Ukraine).

Since the representatives of the H clade of mtDNA comprised 28.6% of the sample, authors suggested a genetic link between the Trypillian population at Verteba and the Funnel Beaker culture groups, which displayed similar frequencies of H-bearing haplotypes.

Three of the specimens also showed considerable amounts of steppe-related ancestry, suggesting influx into the CTCC gene-pool from people affiliated with the steppe populations of the North Pontic.

However, these samples also show the presence of steppe[88] EHG, CHG, and WHG components as described in Mathiesson et al., with the exception of one individual (I3151), who seems to be absent of any EHG/CHG ancestry".

[41] According to the paper, it indicates shared ancestry with the population of Baden culture, "in conclusion, the results show that Verteba Cave represents a significant mortuary site that connects East and West.