Cueva de las Manos

[9] During the time of the Paleoindians, around the late Pleistocene to early Holocene geological periods, the areas between 400 and 500 meters (1,300 and 1,600 ft) above sea level formed a microclimate in the canyon promoting a grassland ecosystem hospitable to many animals.

[16] In ancient times, people accessed the Pinturas Canyon, and by extension the cave area, through ravines in the east and west, typically from higher elevations around 600 to 700 meters (2,000 to 2,300 ft) above sea level.

[20] When the site was occupied, the Pinturas and Deseado Rivers drained into the Atlantic Ocean and provided water for herds of guanacos, making the area attractive to Paleoindians.

The resulting reduction in water levels of the Pinturas and Deseado rivers led to a progressive abandonment of the Cueva de las Manos site.

[22] Projectile points, a bola stone fragment, side-scrapers, and fire pits[23] have been found alongside the remains of guanaco, puma, fox, birds, and other small animals.

Archaeologist Francisco Mena states: "[in the] Middle to Late Holocene Adaptations in Patagonia ... neither agriculture nor fully fledged pastoralism ever emerged.

"[30] Argentine surveyor and archaeologist Carlos J. Gradin remarks in his writings that all the rock art in the area shows the hunter-gatherer lifestyle of the artists who made it.

[32][33][19] Beginning around 7,500 BC, the site, along with the Cerro Casa de Piedra-7 site near Lake Burmeister, became important landmarks in a nomadic circuit[34] between Pinturas Canyon and its surrounding areas, the western part of the Central High Plateau, and the steppes and forests of the ecotone bordering the steppes and forests of the mountainous-lake environment of the Andes.

[35] When occupying the area, temporary camp sites would be made around the cave, where extended families or even large bands of people would gather.

[27] The site was last inhabited around 700 AD, with the final cave dwellers possibly being ancestors of the Tehuelche tribes.

[1] Argentine surveyor and archaeologist Carlos Gradin and his team began the most substantial research on the site in 1964, initiating a 30-year-long study of the caves and their art.

[43] In 1995, the site became a major subject in a study of Argentina's rock art initiated by the National Institute of Anthropology and Latin American Thought (INAPL).

[44] This study led to Cueva de las Manos being listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999.

[45] In 2018, the site received its own provincial park,[9] and as of 2020 the land is controlled directly by the state, after being donated by Rewilding Argentina.

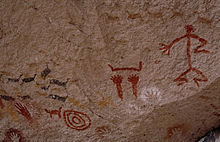

[48] Cueva de las Manos is named for the hundreds of hand paintings stenciled into multiple collages on the rock walls.

[52][53] Scholars Ralph Crane and Lisa Fletcher assert that the rock art at Cueva de las Manos includes the oldest-known cave paintings in South America.

[68] There are also depictions of human beings, guanacos,[36] rheas, felines, south Andean deer,[69] and other animals, as well as geometric shapes, zigzag patterns, representations of the sun, and hunting scenes.

[25] However, that so many people contributed to the artwork for thousands of years suggests the cave held great significance for the artists who painted on its walls.

[72] Regardless of its purpose, the artwork played a key role in the collective social memories of the peoples who inhabited the area, with earlier groups influencing later ones through a narrative spanning millennia.

[73] Important aspects of the culture of the hunter-gatherers are shown in the themes of the art, such as the reproductive cycles of guanacos and collective hunting.

[73] The site also bore a deep social and personal connection to the artists, as the same groups returned to the location seasonally and created artwork at the cave, which was a kind of ritual.

"[74] Instead, Clottes asserts that prehistoric shamanism is the most plausible explanation for the purpose of the artwork, as part of "ceremonies about which we will never know anything", although he acknowledges that this hypothesis does not explain everything, and that much work still needs to be done.

[74] Another hypothesis posits that the art served as boundary markers between peoples, showing territoriality and ensuring the cooperation of others by functioning as aggregation sites.

[79] Regardless, the fact that many people gathered in one place to contribute to the rock art for such a long period shows a large cultural significance, or at least usefulness, to those who participated.

[57] Specialists have categorized the art into four stylistic groups, as proposed by Carlos Gradin and adapted and modified by others:[82] A, B, B1, and C,[83] also known as Río Pinturas I, II, III, and IV, respectively.

[85] Stylistic group A ended during the H1 eruption of the Hudson volcano, which took place around 4,770/4,675 BC[86] and led to the abandonment of the Rio Pinturas Area.

[4][37] Every February the nearby town of Moreno hosts a celebration in honor of the caves[4][90] called Festival Folklórico Cueva de las Manos.

[31] A team of professionals from the INAPL and the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) supervised the construction of these facilities.

[101] The provincial government in particular has been criticized for falling short of the recommendations of the INAPL, including the need for additional staffing and a permanent on-site archaeologist.