Cultural anthropology

Much of anthropological theory has originated in an appreciation of and interest in the tension between the local (particular cultures) and the global (a universal human nature, or the web of connections between people in distinct places/circumstances).

[2] Cultural anthropology has a rich methodology, including participant observation (often called fieldwork because it requires the anthropologist spending an extended period of time at the research location), interviews, and surveys.

[4] Cultural anthropology emerged in the late 19th century, shaped by debates over what constituted "primitive" versus "civilized" societies, an issue that preoccupied not only Freud, but many of his contemporaries.

[5] The first generation of cultural anthropologists were interested in the relative status of various humans, some of whom had modern advanced technologies, while others lacked anything but face-to-face communication techniques and still lived a Paleolithic lifestyle.

Some of those who advocated "independent invention", like Lewis Henry Morgan, additionally supposed that similarities meant that different groups had passed through the same stages of cultural evolution (See also classical social evolutionism).

Although 19th-century ethnologists saw "diffusion" and "independent invention" as mutually exclusive and competing theories, most ethnographers quickly reached a consensus that both processes occur, and that both can plausibly account for cross-cultural similarities.

Analyses of large human concentrations in big cities, in multidisciplinary studies by Ronald Daus, show how new methods may be applied to the understanding of man living in a global world and how it was caused by the action of extra-European nations, so highlighting the role of Ethics in modern anthropology.

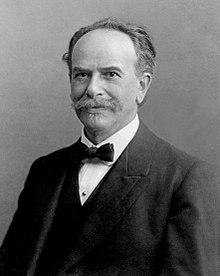

Boas, originally trained in physics and geography, and heavily influenced by the thought of Kant, Herder, and von Humboldt, argued that one's culture may mediate and thus limit one's perceptions in less obvious ways.

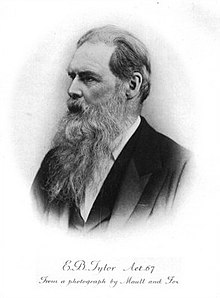

Like other scholars of his day (such as Edward Tylor), Morgan argued that human societies could be classified into categories of cultural evolution on a scale of progression that ranged from savagery, to barbarism, to civilization.

Influenced by the German tradition, Boas argued that the world was full of distinct cultures, rather than societies whose evolution could be measured by the extent of "civilization" they had.

His first generation of students included Alfred Kroeber, Robert Lowie, Edward Sapir, and Ruth Benedict, who each produced richly detailed studies of indigenous North American cultures.

Influenced by psychoanalytic psychologists including Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, these authors sought to understand the way that individual personalities were shaped by the wider cultural and social forces in which they grew up.

Boas had planned for Ruth Benedict to succeed him as chair of Columbia's anthropology department, but she was sidelined in favor of Ralph Linton,[16] and Mead was limited to her offices at the AMNH.

In England, British Social Anthropology's paradigm began to fragment as Max Gluckman and Peter Worsley experimented with Marxism and authors such as Rodney Needham and Edmund Leach incorporated Lévi-Strauss's structuralism into their work.

Authors such as David Schneider, Clifford Geertz, and Marshall Sahlins developed a more fleshed-out concept of culture as a web of meaning or signification, which proved very popular within and beyond the discipline.

[24] Nevertheless, key aspects of feminist theory and methods became de rigueur as part of the 'post-modern moment' in anthropology: Ethnographies became more interpretative and reflexive,[25] explicitly addressing the author's methodology; cultural, gendered, and racial positioning; and their influence on the ethnographic analysis.

[26] Currently anthropologists pay attention to a wide variety of issues pertaining to the contemporary world, including globalization, medicine and biotechnology, indigenous rights, virtual communities, and the anthropology of industrialized societies.

To establish connections that will eventually lead to a better understanding of the cultural context of a situation, an anthropologist must be open to becoming part of the group, and willing to develop meaningful relationships with its members.

This helps to standardize the method of study when ethnographic data is being compared across several groups or is needed to fulfill a specific purpose, such as research for a governmental policy decision.

It is meant to be a holistic piece of writing about the people in question, and today often includes the longest possible timeline of past events that the ethnographer can obtain through primary and secondary research.

Notable proponents of this approach include Arjun Appadurai, James Clifford, George Marcus, Sidney Mintz, Michael Taussig, Eric Wolf and Ronald Daus.

Also growing more popular are ethnographies of professional communities, such as laboratory researchers, Wall Street investors, law firms, or information technology (IT) computer employees.

All humans recognize fathers and mothers, sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, uncles and aunts, husbands and wives, grandparents, cousins, and often many more complex types of relationships in the terminologies that they use.

[37] In the twenty-first century, Western ideas of kinship have evolved beyond the traditional assumptions of the nuclear family, raising anthropological questions of consanguinity, lineage, and normative marital expectation.

[36] Instead of relying on narrow ideas of Western normalcy, kinship studies increasingly catered to "more ethnographic voices, human agency, intersecting power structures, and historical context".

At this time, there was the arrival of "Third World feminism", a movement that argued kinship studies could not examine the gender relations of developing countries in isolation and must pay respect to racial and economic nuance as well.

This critique became relevant, for instance, in the anthropological study of Jamaica: race and class were seen as the primary obstacles to Jamaican liberation from economic imperialism, and gender as an identity was largely ignored.

In Jamaica, marriage as an institution is often substituted for a series of partners, as poor women cannot rely on regular financial contributions in a climate of economic instability.

These anthropological findings, according to Third World feminism, cannot see gender, racial, or class differences as separate entities, and instead must acknowledge that they interact together to produce unique individual experiences.

There have also been issues of reproductive tourism and bodily commodification, as individuals seek economic security through hormonal stimulation and egg harvesting, which are potentially harmful procedures.