Cultural life of Theresienstadt Ghetto

Theresienstadt was originally designated as a model community for middle-class Jews from Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Austria.

In a propaganda effort designed to fool the western allies, the Nazis publicised the camp for its rich cultural life.

In reality, according to a Holocaust survivor, "during the early period there were no [musical] instruments whatsoever, and the cultural life came to develop itself only ... when the whole management of Theresienstadt was steered into an organized course.

The history of the magazine was studied and narrated by the Italian writer Matteo Corradini in his book La repubblica delle farfalle (The Republic of the Butterflies).

Sir Ben Kingsley read that novel, speaking on 27 January 2015 during the ceremony held at Theresienstadt to mark International Holocaust Memorial Day.

[2] Violinist Julius Stwertka, a former leading member of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and co-leader of the Vienna Philharmonic, was murdered in the camp on 17 December 1942.

[citation needed] Pianist Alice Herz-Sommer (held with her son, Raphael Sommer) performed 100 concerts while imprisoned at Theresienstadt.

Some were preserved and later published in a collection called I Never Saw Another Butterfly, its title taken from a poem by young Jewish Czech poet Pavel Friedmann.

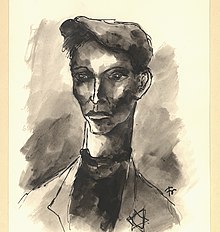

[4] Artist and architect Norbert Troller produced drawings and watercolours of life inside Theresienstadt, to be smuggled to the outside world.

It was planned for performance at the camp, but the Nazis withdrew permission when it was in rehearsal, probably because the authorities perceived its allegorical intent.

[6][7] The collection features music composed mostly in 1943 and 1944 by Pavel Haas, Gideon Klein, Hans Krása, and Viktor Ullmann while interned at Theresienstadt.

In 2008, Bridge Records released a recital by Austrian baritone Wolfgang Holzmair and American pianist Russell Ryan that drew on a different selection of songs.

Scholars have interpreted acts of cultural expression through theater, music, and art in Theresienstadt as a strategy for survival by those deported there.

[10] The Nazis decided that Theresienstadt could function uniquely as a place to deport members of Europe’s cultural elite.

Art in the ghetto underwent drastic development as it allowed for depiction and representation of true life in Theresienstadt.

[14] Despite constant deportations of inmates to the East, the ghetto inhabitants remained determined to continue performing and creating.