Culture of Artsakh

They began developing in the pre-Christian times, proceeded through the adoption of Christianity early in the fourth century, and entered the era of modernity after blossoming in the Middle Ages.

Names of castles and fortresses in Nagorno Karabakh like in the rest of historical Artsakh and Armenia, customarily include the term "berd" (Armenian: բերդ) which means "fort."

[15][16] They originally appeared during the reign of the Artashessian (Artaxiad) royal dynasty in Armenia (190 BC-53 AD) who used the stones, with inscriptions, to demarcate the kingdom's frontiers for travelers.

Գրիգորիս), St. Gregory's grandson and Bishop of Aghvank, who was killed by the pagans, around 338 AD, when teaching Gospel in the land of the Mazkuts (present-day Republic of Dagestan, in Russia).

[4][37] Several monastic churches from this period adopted the model used most widely throughout Armenia: a cathedral with a cupola in the inscribed cross plan with two or four angular chambers.

In the case of the Gandzasar and Gtichavank monasteries, the cone over the cupola is umbrella-shaped, a picturesque design that was originally developed by the architects of Armenia's former capital city of Ani, in the tenth century, and subsequently spread to other provinces of the country, including Artsakh.

[38] In this regard, the thirteenth century's Dadivank, the largest monastic complex in Artsakh and all of Eastern Armenia, located in the northwestern corner of the Mardakert District, is a remarkable case.

With its Memorial Cathedral of the Holy Virgin in the center, Dadivank has approximately twenty different structures, which are divided into four groups: ecclesiastical, residential, defensive and ancillary.

The Gandzasar Monastery was the spiritual center of Khachen (Armenian: Խաչեն), the largest and most powerful principality in medieval Artsakh, by virtue of being home to the Katholicosate of Aghvank.

[48] After the Cathedral of St. Cross on the Lake Van (also known as Akhtamar-Ախթամար, in Turkey), Gandzasar contains the largest amount of sculpted decor compared to other architectural ensembles of Armenia.

Եղիշե Առաքյալ, also known as the Jrvshtik Monastery (Ջրվշտիկ), which in Armenian means "Longing-for-Water"), in the historical county of Jraberd, that has eight single-naved chapels aligned from north to south.

One of these chapels is a site of high importance for the Armenians, as it serves as a burial ground for Artsakh's fifth-century monarch King Vachagan II the Pious Arranshahik.

The most famous of those tells how Vachagan fell in love with the beautiful and clever Anahit, who then helped the young king defeat pagan invaders.

In the city of Shusha, three nineteenth-century mosques were built, which, together with two Russian Orthodox chapels, are the only non-Armenian architectural monuments found on the territories comprising the former Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Region and today's Republic of Artsakh.

That special style synthesized designs used in building grand homes in Artsakh's rural areas (especially in the southern county of Dizak) and elements of neo-classical European architecture.

In the same century, however, the monastery was rebuilt under the patronage of Prince Yesai (Armenian: Եսայի Իշխան Առանշահիկ), Lord of Dizak, who bravely fought against the invaders.

In 1223, as testified by the Bishop Stephanos Orbelian (died in 1304), Amaras was looted again—at this time, by the Mongols—who took with them St. Grigoris' crosier and a large golden cross decorated with 36 precious stones.

However, during the early 20th century the cities cosmopolitan and tolerant attitude began to fall apart, and became a venue of sporadic inter-communal violence, but it was in March 1920 when it received the deadliest blow of all.

The Azerbaijani Army intentionally targeted Armenian Christian monuments for the purpose of their demolition, using, among a variety of means, heavy artillery and military airplanes.

[74] Robert Bevan writes: "The Azeri campaign against the Armenian enclave of Nagorno Karabakh which began in 1988 was accompanied by cultural cleansing that destroyed the Egheazar monastery and 21 other churches.

[76] When the Principality of Khachen forged ties with the Kingdom of Cilicia (1080–1375), an independent Armenian state on the Mediterranean Sea that aided the Crusaders, a small number of Artsakh's fortifications acquired a certain Cilician look as a result.

Backed by an intricate system of camps, recruiting centers, watchtowers and fortified beacons, both belonged to the so-called Lesser Syghnakh (Armenian: Փոքր Սղնախ), which was one of Artsakh's two main historical military districts responsible for defending the southern counties of Varanda and Dizak.

[80][81] Khachkars (Armenian: խաչքար), stone slab monuments decorated with a cross, represent a special chapter in the history of sculpture, and are unique to historical Armenia.

Covering the walls of churches and monasteries with ornamented texts in Armenian developed in Artsakh, and in many other places in historical Armenia, into a unique form of decor.

While [my sons] were alive, they vowed to build a church to the glory of God … and I undertook the construction of this expiatory temple with utmost hope and diligence, for the salvation of their souls, and mine and all of my nephews.

The fresco on the northern wall represents the birth of Jesus: Saint Joseph stands at Mary's bedside, and the three magicians kneel in adoration in front; cherubs fly in the sky above them, singing Glory in Highest Heaven.

[91] A group of illuminated works is specific to the regions of Artsakh and Utik; in their linear and unadorned style they resemble miniatures of the Syunik and Vaspurakan schools.

Besides depicting biblical stories, several of Artsakh's manuscripts attempt to convey the images of the rulers of the region who often ordered the rewriting and illumination of the texts.

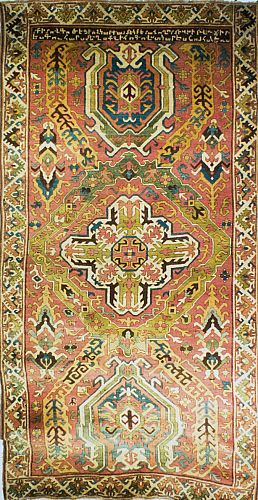

Two accounts by the historian Kirakos Gandzaketsi mention embroideries and altar curtains handmade by his contemporaries Arzou and Khorishah—two princesses of the House of Upper Khachen (Haterk/Հաթերք)—for the Dadivank Monastery.

[90] In the 19th century, local rugs and samples of natural silk production became part of international exhibitions and art fairs in Moscow, Philadelphia and Paris.