Culture of the Asante Empire

At its peak from the 18th–19th centuries, the Empire extended from the Komoé River (Ivory Coast) in the West to the Togo Mountains in the East.

"They were courteous, well-mannered, dignified and proud of their honor to such an extent a social disgrace, including something unintended as public flatulence could drive a man to commit suicide.

[4] Historian Edgerton describes the wealth of Asante in the mid 19th century where he states it was not uncommon for members who worked with the royal administration to possess over £100,000 in gold.

The father had fewer legal responsibilities for his children with the exception of ensuring their well-being and to pay for a suitable wife for his son.

[9] Some women wore Kente cloth dresses made by stitching together numerous handwoven strips of cotton or silk.

[citation needed] Plants cultivated by the Asante include plantains, yams, manioc, corn, sweet potatoes, millet, beans, onions, peanuts, tomatoes, and many fruits.

She cites William Hutton in 1820 who observed the presence of poultry, sheep and hogs of which the Asante lower class preferred to sell as they could not afford such diet.

The welfare of Asante slaves varied from being able to acquire wealth and intermarry with the master's family to being sacrificed in funeral ceremonies.

The construction and design of most Asante houses consisted of a timber framework filled up with clay which were thatched with sheaves of leaves.

Generally, houses whether designed for human habitation or for the deities, consisted of four separate rectangular single-room buildings set around an open courtyard; the inner corners of adjacent buildings were linked by means of splayed screen walls, whose sides and angles could be adapted to allow for any inaccuracy in the initial layout.

The steps and raised floor of these rooms were clay and stone, with a thick layer of red earth, which abounds in the neighbourhood, and these were washed and painted daily, With an infusion of the same earth in water; it has all the appearance of red ochre, and from the abundance of iron ore in the neighbourhood, I do not doubt it... A white wash, very frequently renewed, was made from a clay in the neighbourhood...The doors were an entire piece of cotton wood, cut with great labour out of the stems or buttresses of that tree...Where they raised a first floor, the under room was divided into two by an intersecting wall, to support the rafters for the upper room, which were generally covered with a frame work thickly plastered over with red ochre....In Kumasi, adampan[a] were loggias opened on to the streets of the city.

He argues the dampan was an unstructured forum to raise household matters in public, to exchange information or to promote social interaction.

[33] These were elevated mounds built out of sun-baked clay that served as a platform for the Asantehene to sit and preside over public rituals in Kumasi.

[35] The earliest description of the sumpene comes from Bowdich's journal in 1819 where he observed circular elevations of two steps, "the lower about 20 feet in circumference, like the bases of the old market crosses in England."

Around these ledges the officers of the Household, with attendant domestics take their seats and thus a group is formed of from fifty to a hundred persons all distinctively seen.

[39] Bowdich mentioned the "King's garden" as a part of the palace complex in 1817, which was "an area equal to one of the large squares in London.

[42] One part of the Aban housed the wine store while most served the purpose of displaying the Asantehene's collection of arts and crafts.

Christian Missionary, Freeman, reported of his visit to the Aban in 1841 where he noted several articles of manufactured glass on display in various rooms.

Books in many languages, Bohemian glass, clocks, silver plate, old furniture, Persian rugs, Kidderminster carpets, pictures and engravings, numberless chests and coffers... With these were many specimens of Moorish and Ashanti handicraft...”[43] Gold was an fundamental part of Asante art.

[44] Most goldweights are miniature representations of West African cultural items such as the adinkra symbols, plants, animals and people.

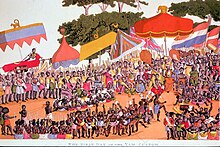

The custom of holding this festival came into prominence between 1697 and 1699 when statehood was achieved for the people of Ashante after the war of independence, at the Battle of Feyiase, against the Denkyira.

The Annual Yam Festival celebrated between September and December, reinforced bonds of loyalty and patriotism to Asante.

Crimes committed by notables were intentionally withheld until the festival, where they faced trial and execution to serve as an object of lesson to all.

Asante houses included Nyame dua that served as shrines for seeking solace or quietus in addressing Onyame.

When death occurred, the soul was believed to leave the physical body and inhabit the land of spirits where he or she would live a life similar on Earth.

[52] Through trade and wars of conquest, a number of Muslims from Northern Ghana formed part of Asante's bureaucracy.

The sasabonsam had the appearance of the torso of a tall ape, the head and teeth of a carnivore, the underside of a snake and sometimes, the wings of a bat.

The creature was believed to hook its feet onto trees where it hid from plain sight in order to trap and devour unsuspecting humans.

According to Fynn, the common diseases among the Asante in the early 19th century were discovered to be lues, yaws, itches, scald heads, gonorrhea and pains in the bowels.

It was testified by Dr. Teddlie who was an assistant surgeon of the Bowdich Mission on visit to Kumasi in 1817, that herbalists in Asante were treating all kinds of diseases and illness with green leaves, roots and barks of a lot of trees.