Yup'ik

The neighbours of the Yupʼik are the Iñupiaq to the north, Aleutized Alutiiq ~ Sugpiaq to the south, and Alaskan Athabaskans, such as Yupikized Holikachuk and Deg Hitʼan, non-Yupikized Koyukon and Denaʼina, to the east.

[11] Before a Russian colonial presence emerged in the area, the Aleut and Yupik spent most of their time sea-hunting animals such as seals, walruses, and sea lions.

The Indigenous peoples were forced to pay taxes in the form of beaver and seal fur and opted to do so rather than fight the ever-growing stream of Russian hunters.

[19] James W. VanStone (1925–2001), an American cultural anthropologist, and Wendell H. Oswalt were among the earliest scholars to undertake significant archaeological research in the Yupʼik region.

[19] Ann Fienup-Riordan (born 1948) began writing extensively about the Yukon-Kuskokwim Indigenous people in the 1980s; she melded Yupʼik voices with traditional anthropology and history in an unprecedented fashion.

[19] A more scholarly, yet similar, treatment of cultural change can be found in Angayuqaq Oscar Kawagley's A Yupiaq Worldview: a Pathway to Ecology and Spirit (2001), which focuses on the intersection of Western and Yupʼik values.

[21] Yuuyaraq defined the correct way of thinking and speaking about all living things, especially the great sea and land mammals on which the Yupʼik relied for food, clothing, shelter, tools, kayaks, and other essentials.

[23] Elders-in-residence is a program that involves elders in teaching and curriculum development in a formal educational setting (oftentimes a university), and is intended to influence the content of courses and the way the material is taught.

[28] Although there were no formally recognized leaders, informal leadership was practiced by or in the men who held the title Nukalpiaq ("man in his prime; successful hunter and good provider").

Raising children was the women's responsibility until young boys left the home to join other males in the qasgiq to learn discipline and how to make a living.

[27] The ena also served as a school and workshop for young girls, where they could learn the art and craft of skin sewing, food preparation, and other important survival skills.

[27] Although there were no formally recognized leaders or offices to be held, men and boys were assigned specific places within the qasgiq that distinguished the rank of males by age and residence.

[27] Prior to and during the mid-19th century, the time of Russian exploration and presence in the area, the Yupiit were organized into at least twelve, and perhaps as many as twenty, territorially distinct regional or socio-territorial groups (their native names will generally be found ending in -miut postbase which signifies "inhabitants of ..." tied together by kinship[30][31]—hence the Yupʼik word tungelquqellriit, meaning "those who share ancestors (are related)".

[31] These groups included: While Yupiit were nomadic, the abundant fish and game of the Y-K Delta and Bering Sea coastal areas permitted for a more settled life than for many of the more northerly Iñupiaq people.

Today, snowmobile or snowmachine travel is a critical component of winter transport; an ice road for highway vehicles is used along portions of the Kuskokwim River.

[46] Caninermiut style Yupʼik kayak used in the Kwigillingok and Kipnuk regions and there are teeth marks in the wood of the circular hatch opening, made by the builders as they bent and curved the driftwood into shape.

The dog sleds (ikamraq sg ikamrak dual ikamrat pl in Yupʼik and Cupʼik, qamauk in Yukon and Unaliq-Pastuliq Yupʼik, ikamrag, qamaug in Cupʼig; often used in the dual for one sled)[49] are an ancient and widespread means of transportation for Northern Indigenous peoples, but when non-Native fur traders and explorers first traveled the Yukon River and other interior regions in the mid-19th century they observed that only Yupikized Athabaskan groups, including the Koyukon, Deg Hitʼan and Holikachuk, used dogs in this way.

[67][68] The stories that previous generations of Yupʼik heard in the qasgi and assimilated as part of a life spent hunting, traveling, dancing, socializing, preparing food, repairing tools, and surviving from one season to the next.

Everyday functional items like skin mittens, mukluks, and jackets are commonly made today, but the elegant fancy parkas (atkupiaq) of traditional times are now rare.

[72][73] The National Museum of the American Indian, as a part of the Smithsonian Institution, provided photographs of Yupʼik ceremonial masks collected by Adams Hollis Twitchell, an explorer and trader who traveled Alaska during the Nome Gold Rush newly arrived in the Kuskokwim region, in Bethel in the early 1900s.

Yupʼik settled where the water remained ice-free in winter, where walruses, whales, and seals came close to shore, and where there was a fishing stream or a bird colony nearby.

The coastal settlements rely more heavily on sea mammals (seals, walrusses, beluga whales), many species of fish (Pacific salmon, herring, halibut, flounder, trout, burbot, Alaska blackfish), shellfish, crabs, and seaweed.

The inland settlements rely more heavily on Pacific salmon and freshwater whitefish, land mammals (moose, caribou), migratory waterfowl, bird eggs, berries, greens, and roots help sustain people throughout the region.

The cabin on-post form may thus have been introduced by early traders, miners, or missionaries, who would have brought with them memories of the domestic and storage structures constructed in their homelands.

[82][83] Muktuk (mangtak in Yukon, Unaliq-Pastuliq, Chevak, mangengtak in Bristol Bay) is the traditional meal of frozen raw beluga whale skin (dark epidermis) with attached subcutaneous fat (blubber).

Aboriginally and in early historic times the shaman, called as medicine man or medicine woman (angalkuq sg angalkuk dual angalkut pl or angalkuk sg angalkuuk dual angalkuut pl in Yupʼik and Cupʼik, angalku in Cupʼig) was the central figure of Yupʼik religious life and was the middle man between spirits and the humans.

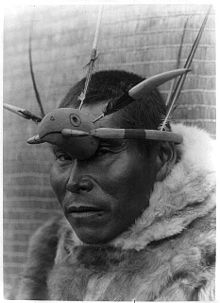

Shamans wearing masks of bearded seal, moose, wolf, eagle, beaver, fish, and the north wind were accompanied by drums and music.

In 1885, the Moravian Church established a mission in Bethel, under the leadership of the Kilbucks and John's friend and classmate William H. Weinland (1861–1930) and his wife with carpenter Hans Torgersen.

Chamber pots (qurrun in Yupʼik and Cupʼik, qerrun in Cupʼig) or honey buckets with waterless toilets are common in many rural villages in the state of Alaska, such as those in the Bethel area of the Yukon–Kuskokwim Delta.

The 1986 statutes have remained in effect since that time, with only relatively minor amendments to formalize the prohibition on home brew in a dry community (teetotal) and clarify the ballot wording and scheduling of local option referendums.