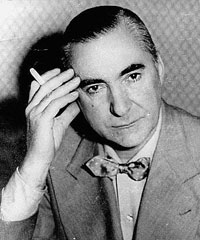

Curzio Malaparte

After the Second World War, he became a filmmaker and moved closer to both Togliatti's Italian Communist Party and the Catholic Church (though once a staunch atheist), reputedly becoming a member of both before his death.

As a member of the Partito Nazionale Fascista, he founded several periodicals and contributed essays and articles to others, as well as writing numerous books, starting from the early 1920s, and directing two metropolitan newspapers.

The book emphasizes that Joseph Stalin thoroughly comprehended the technical aspects employed by Trotsky and so was able to avert Left Opposition coup attempts better than Kerensky.

This led to Malaparte being stripped of his National Fascist Party membership and sent to internal exile from 1933 to 1938 on the island of Lipari.

During that time (1938–41) he built a house with the architect Adalberto Libera, known as the Casa Malaparte, on Capo Massullo, on the Isle of Capri.

The articles he sent back from the Ukrainian Fronts, many of which were suppressed, were collected in 1943 and brought out under the title The Volga Rises in Europe.

Their appearance is miserable, their cruelty sad, their courage silent and hopeless.In the foreword to Kaputt, Malaparte describes in detail the convoluted process of writing.

Souchena's young wife, absorbed in Eugene Onegin after a hard day's work, reminded Malaparte of Elena and Alda, the two daughters of Benedetto Croce.

One of the most well-known and often quoted episodes of Kaputt concerns the interview which Malaparte - as an Italian reporter, supposedly on the Axis side - had with Ante Pavelić, who headed the Croat puppet state set up by the Nazis.

The lid was raised and the basket seemed to be filled with mussels, or shelled oysters, as they are occasionally displayed in the windows of Fortnum and Mason in Piccadilly in London.

"Milan Kundera's view of the Kaputt is summarized in his essay The Tragedy of Central Europe:[8] It is strange, yes, but understandable: for this reportage is something other than reportage; it is a literary work whose aesthetic intention is so strong, so apparent, that the sensitive reader automatically excludes it from the context of accounts brought to bear by historians, journalists, political analysts, memoirists.

[9]According to D. Moore's editorial note, in The Skin, Malaparte extends the great fresco of European society he began in Kaputt.

In all the literature that derives from the Second World War, there is no other book that so brilliantly or so woundingly presents triumphant American innocence against the background of the European experience of destruction and moral collapse.

It was released in the United States in 1953 as Strange Deception and voted among the five best foreign films by the National Board of Review.

Malaparte visited China in 1956 to commemorate the death of the Chinese essay and fiction writer, Lu Xun.

But at the time of his death in 1957 there were no diplomatic relations with the People's Republic, so the transfer could not take place, and the family succeeded in changing the will.

In the collection of writings Mamma marcia, published posthumously in 1959, Malaparte writes about the youth of the post-Second World War era with homophobic tones, describing it as effeminate and tending to homosexuality and communism;[16] the same content is expressed in the chapters "The pink meat" and "Children of Adam" of The Skin.

An American journalist, Percy Winner, wrote about their relationship during the fascist ventennio (twenty year period) and the Allied Occupation of Italy, in the lightly fictionalized novel, Dario (1947) (where the main character's last name is Duvolti, or a play on "two faces").