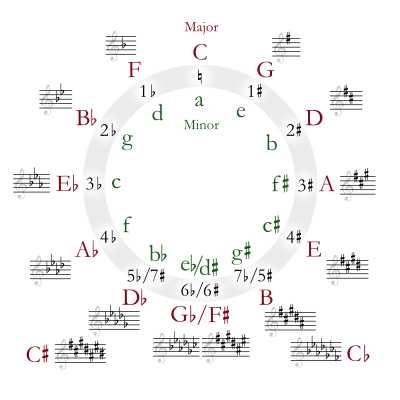

Circle of fifths

Starting on a C, and using the standard system of tuning for Western music (12-tone equal temperament), the sequence is: C, G, D, A, E, B, F♯/G♭, C♯/D♭, G♯/A♭, D♯/E♭, A♯/B♭, F, and C. This order places the most closely related key signatures adjacent to one another.

The circle of fifths is used to organize and describe the harmonic or tonal function of chords.

[3] In this view the tonic or tonal center is considered the end point of a chord progression derived from the circle of fifths.

According to Richard Franko Goldman's Harmony in Western Music, "the IV chord is, in the simplest mechanisms of diatonic relationships, at the greatest distance from I.

Twelve-tone equal temperament tuning produces fifths that return to a tone exactly seven octaves above the initial tone and makes the frequency ratio of the chromatic semitone the same as that of the diatonic semitone.

Ascending by twelve justly tuned fifths fails to close the circle by an excess of approximately 23.46 cents, roughly a quarter of a semitone, an interval known as the Pythagorean comma.

The first circle of fifths diagram appears in the Grammatika (1677) of the composer and theorist Nikolay Diletsky, who intended to present music theory as a tool for composition.

[7] It was "the first of its kind, aimed at teaching a Russian audience how to write Western-style polyphonic compositions."

A circle of fifths diagram was independently created by German composer and theorist Johann David Heinichen in his Neu erfundene und gründliche Anweisung (1711),[8] which he called the "Musical Circle" (German: Musicalischer Circul).

More commonly, composers make use of "the compositional idea of the 'cycle' of 5ths, when music moves consistently through a smaller or larger segment of the tonal structural resources which the circle abstractly represents.

Here is how the circle of fifths derives, through permutation from the diatonic major scale: And from the (natural) minor scale: The following is the basic sequence of chords that can be built over the major bass-line: And over the minor: Adding sevenths to the chords creates a greater sense of forward momentum to the harmony: According to Richard Taruskin, Arcangelo Corelli was the most influential composer to establish the pattern as a standard harmonic "trope": "It was precisely in Corelli's time, the late seventeenth century, that the circle of fifths was being 'theorized' as the main propellor of harmonic motion, and it was Corelli more than any one composer who put that new idea into telling practice.

In the following, from Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen, BWV 51, even when the solo bass line implies rather than states the chords involved: Handel uses a circle of fifths progression as the basis for the Passacaglia movement from his Harpsichord suite No.

Baroque composers learnt to enhance the "propulsive force" of the harmony engendered by the circle of fifths "by adding sevenths to most of the constituent chords."

"These sevenths, being dissonances, create the need for resolution, thus turning each progression of the circle into a simultaneous reliever and re-stimulator of harmonic tension...

"[19] Striking passages that illustrate the use of sevenths occur in the aria "Pena tiranna" in Handel's 1715 opera Amadigi di Gaula: – and in Bach's keyboard arrangement of Alessandro Marcello's Concerto for Oboe and Strings.

Franz Schubert's Impromptu in E-flat major, D 899, contains harmonies that move in a modified circle of fifths: The Intermezzo movement from Mendelssohn's String Quartet No.2 has a short segment with circle-of-fifths motion (the ii° is substituted by iv): Robert Schumann's "Child falling asleep" from his Kinderszenen uses the progression, changing it at the end—the piece ends on an A minor chord, instead of the expected tonic E minor.

In Wagner's opera, Götterdämmerung, a cycle of fifths progression occurs in the music which transitions from the end of the prologue into the first scene of Act 1, set in the imposing hall of the wealthy Gibichungs.

"Status and reputation are written all over the motifs assigned to Gunther",[20] chief of the Gibichung clan: The enduring popularity of the circle of fifths as both a form-building device and as an expressive musical trope is evident in the number of "standard" popular songs composed during the twentieth century.

It is also favored as a vehicle for improvisation by jazz musicians, as the circle of fifths helps songwriters understand intervals, chord-relationships and progressions.

By contrast, the circle of fifths is fundamentally a discrete structure arranged through distinct intervals, and there is no obvious way to assign pitch classes to each of its points.

The circle of fifths, or fourths, may be mapped from the chromatic scale by multiplication, and vice versa.

In twelve-tone equal temperament, one can start off with an ordered 12-tuple (tone row) of integers: representing the notes of the chromatic scale: 0 = C, 2 = D, 4 = E, 5 = F, 7 = G, 9 = A, 11 = B, 1 = C♯, 3 = D♯, 6 = F♯, 8 = G♯, 10 = A♯.

The adjustment made in equal temperament tuning is called the Pythagorean comma.