Cyclol

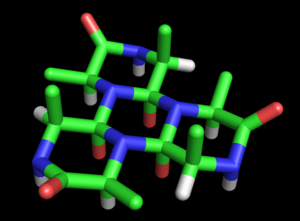

These crosslinks are covalent analogs of the non-covalent hydrogen bonds between peptide groups and have been observed in rare cases, such as the ergopeptides.

Based on this reaction, mathematician Dorothy Wrinch hypothesized in a series of five papers in the late 1930s a structural model of globular proteins.

She further proposed that globular proteins have a tertiary structure corresponding to Platonic solids and semiregular polyhedra formed of cyclol fabrics with no free edges.

By the mid-1930s, analytical ultracentrifugation studies by Theodor Svedberg had shown that proteins had a well-defined chemical structure, and were not aggregations of small molecules.

[8] The most accepted (and ultimately correct) hypothesis was that proteins are linear polypeptides, i.e., unbranched polymers of amino acids linked by peptide bonds.

[9][10] However, a typical protein is remarkably long—hundreds of amino-acid residues—and several distinguished scientists were unsure whether such long, linear macromolecules could be stable in solution.

The process of protein denaturation (as distinguished from coagulation) had been discovered in 1910 by Harriette Chick and Charles Martin,[17] but its nature was still mysterious.

[19] In 1929, Hsien Wu hypothesized correctly that denaturation corresponded to protein unfolding, a purely conformational change that resulted in the exposure of amino-acid side chains to the solvent.

[27][28] The idea that globular proteins are also stabilized by hydrogen bonds was proposed by Dorothy Jordan Lloyd[29][30] in 1932, and championed later by Alfred Mirsky and Linus Pauling.

[21] At a 1933 lecture by Astbury to the Oxford Junior Scientific Society, physicist Charles Frank suggested that the fibrous protein α-keratin might be stabilized by an alternative mechanism, namely, covalent crosslinking of the peptide bonds by the cyclol reaction above.

The idea intrigued J. D. Bernal, who suggested it to the mathematician Dorothy Wrinch as possibly useful in understanding protein structure.

[33] Such fabrics exhibit a long-range, quasi-crystalline order that Wrinch felt was likely in proteins, since they must pack hundreds of residues densely.

Thus, one face is completely independent of the primary sequence of the peptide, which Wrinch conjectured might account for sequence-independent properties of proteins.

[32] Her goals in this article and its successors were to propose a well-defined testable model, to work out the consequences of its assumptions and to make predictions that could be tested experimentally.

Another twenty years had to pass before hydrophobic interactions were recognized as the chief driving force in protein folding.

This was the subject of Wrinch's fourth paper on the cyclol model (1936),[47] written together with Dorothy Jordan Lloyd, who first proposed that globular proteins are stabilized by hydrogen bonds.

[29] A follow-up paper was written in 1937 that referenced other researchers on hydrogen bonding in proteins, such as Maurice Loyal Huggins and Linus Pauling.

She identified a mathematical simplification, in which the non-planar six-membered rings of atoms can be represented by planar "median hexagon"s made from the midpoints of the chemical bonds.

(4) As described above, the cyclol model provided a simple chemical explanation of denaturation and the difficulty of cleaving folded proteins with proteases.

Hans Neurath and Henry Bull showed that the dense packing of side chains in the cyclol fabric was inconsistent with the experimental density observed in protein films.

In particular, she produced a "minimal" closed cyclol of only 48 residues,[68] and, on that (incorrect) basis, may have been the first to suggest that the insulin monomer had a molecular weight of roughly 6000 Da.

[73] However, most protein scientists ceased to believe in it and Wrinch turned her scientific attention to mathematical problems in X-ray crystallography, to which she contributed significantly.

[74] One exception was physicist Gladys Anslow, Wrinch's colleague at Smith College, who studied the ultraviolet absorption spectra of proteins and peptides in the 1940s and allowed for the possibility of cyclols in interpreting her results.

[68] The downfall of the overall cyclol model generally led to a rejection of its elements; one notable exception was J. D. Bernal's short-lived acceptance of the Langmuir-Wrinch hypothesis that protein folding is driven by hydrophobic association.

[65] After a long hiatus during which she worked mainly on the mathematics of X-ray crystallography, Wrinch responded to these discoveries with renewed enthusiasm for the cyclol model and its relevance in biochemistry.