Cyprian Norwid

[4]: viii [8]: 28 [9]: 268 Norwid's first foray into the literary sphere occurred in the periodical Piśmiennictwo Krajowe, which published his first poem, Mój ostatni sonet (My Last Sonnet), in 1840s issue 8.

[4]: vi His early poems were well received by critics and he became a welcome guest at the literary salons of Warsaw; his personality of that time is described as that of a "dandy" and a "rising star" of the young generation of Polish poets.

[7][4]: ix In 1842 Norwid received inheritance funds as well as a private scholarship to study sculpture and left Poland, never to return.

He was also arrested for trying to cross back to Russia without his passport, and his short stay in Berlin prison resulted in partial deafness.

[7] During the European Revolutions of 1848, he stayed in Rome, where he met fellow Polish intellectuals Adam Mickiewicz and Zygmunt Krasiński.

[7] During 1849–1852, Norwid lived in Paris, where he met fellow Poles Frédéric Chopin and Juliusz Słowacki,[7] as well as other emigree artists such as Russians Ivan Turgenev and Alexander Herzen, and other intellectuals such as Jules Michelet (many at Emma Herwegh's salon).

[13]: 28 [14]: 816 Financial hardship, unrequited love, political misunderstandings, and a negative critical reception of his works put Norwid in a dire situation.

[9]: 269 He also suffered from progressive blindness and deafness, but still managed to publish some content in the Polish-language Parisian publication Goniec polski and similar venues.

[20][21] Norwid decided to emigrate to the United States in the Fall of 1852, receiving some sponsorship from Wladysław Zamoyski, a Polish nobleman and philanthropist.

[22]: 190 On 11 February 1853, after a harrowing journey, he arrived in New York City aboard the Margaret Evans, and he held a number of odd jobs there, including at a graphics firm.

This, as well as his disappointment with America, which he felt lacked "history", made him consider a return to Europe, and he wrote to Mickiewicz and Herzen, asking for their assistance.

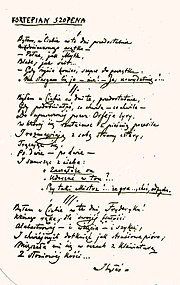

[28][13]: 54–58 The poem's theme is the Russian troops' 1863 defenestration of Chopin's piano from the music school Norwid attended in his youth.

He grew to accept this, and even wrote in one his works that "the sons pass by this writing, but you, my distant grandchild, will read it... when I'll be no more" (Klaskaniem mając obrzękłe prawice... [pl], The Hands Were Swollen by Clapping..., 1858).

[14]: 815 The latter play became Norwid's most frequently performed theater piece, although like many of his works, it gained recognition long after his death (published in print in 1933, and staged in 1936).

[7] Jełowicki and Kleczkjowski personally covered the burial costs, and Norwid's funeral was also attended by Franciszek Duchiński and Mieczysław Geniusz [pl].

[41]: 5 Czesław Miłosz, a Polish poet and Nobel laureate, wrote that "[Norwid] preserved complete independence from the literary currents of the day".

[9]: 271 This could be seen in his short stories, which went against the common trend in the 19th century to write realistic prose and instead are more aptly described as "modern parables".

His style increasingly departing from then-prevailing forms and themes found in romanticism and positivism, and the subjects of his works were also often not aligned with the political views of the emigre Poles.

[41]: 5 Miłosz noted that Norwid was "against aestheticism", and that he aimed to "break the monotony... of the syllabic pattern", purposefully making his verses "roughhewn".

[41]: 5 Miłosz pointed out that Norwid used irony (comparing his use of it to Jules Laforgue or T. S. Eliot), but it was "so hidden within symbols and parables" that it was often missed by most readers.

He also argued that Norwid is "undoubtedly... the most 'intellectual' poet to ever write in Polish", although lack of audience has "permitted him to indulge in such a torturing of the language that some of his lines are hopelessely obscure".

[14]: 814 Miłosz similarly noted that Norwid did not reject civilization, although he was critical of some of its aspects; he saw history as a story of progress "to make martyrdom unnecessary on Earth".

[9]: 280 Following his death, many of Norwid's works were forgotten; it was not until the early 20th century, in the Young Poland period, that his finesse and style was appreciated.

Przesmycki started republishing Norwid's works c. 1897, and created an enduring image of him, one of "the dramatic legend of the cursed poet".

[49][50] On 24 September 2001, 118 years after his death, an urn with soil from the collective grave where Norwid had been interred in Paris' Montmorency cemetery was buried in the "Crypts of the Bards [pl]" at Wawel Cathedral.

[51][52][53] In 2021, on the 200th anniversary of Norwid's birth, the brothers Stephen and Timothy Quay produced a short film titled Vade-mecum about the poet's life and work in an attempt to promote his legacy among foreign audiences.

[42]: 68 In fact, some literary critics of the late 20th-century Poland were skeptical as to the value of Krasiński's work and considered Norwid to be the Third bard instead of Fourth.

[41]: 6 Miłosz acknowledged Vade-mecum as Norwid's most influential work, but also praised the earlier Bema pamięci rapsod żałobny as one of his most famous poems.

[33] Some of Norwid's works have been translated into English by Walter Whipple and Danuta Borchardt in the United States of America, and by Jerzy Pietrkiewicz and Adam Czerniawski in Britain.

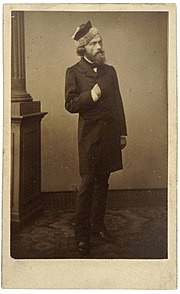

Pantaleon Szyndler