First Czechoslovak Republic

After 1933, Czechoslovakia remained the only de facto functioning democracy in Central Europe, organized as a parliamentary republic.

It also ceded southern parts of Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia to Hungary and the Trans-Olza region in Silesia to Poland.

It was replaced by the Second Czechoslovak Republic, which lasted less than half a year before Germany occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia in March 1939.

Several ethnic groups and territories with different historical, political, and economic traditions were obliged to be blended into a new state structure.

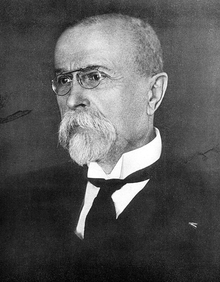

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk had been recognized by World War I Allies as the leader of the Provisional Czechoslovak Government,[2] and in 1920 he was elected the country's first president.

Following the Anschluss of Austria by Germany in March 1938, the Nazi leader Adolf Hitler's next target for annexation was Czechoslovakia.

His pretext was the privations suffered by ethnic German populations living in Czechoslovakia's northern and western border regions, known collectively as the Sudetenland.

The Czechoslovak state was conceived as a parliamentary democracy, guided primarily by the National Assembly, consisting of the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies, whose members were to be elected on the basis of universal suffrage.

From 1928 to 1940, Czechoslovakia was divided into the four "lands" (Czech: "země", Slovak: "krajiny"): Bohemia, Moravia-Silesia, Slovakia, and Carpathian Ruthenia.

Although in 1927 assemblies were provided for Bohemia, Slovakia, and Ruthenia, their jurisdiction was limited to adjusting laws and regulations of the central government to local needs.

The Pětka was headed by Antonín Švehla, who held the office of prime minister for most of the 1920s and designed a pattern of coalition politics that survived until 1938.

A democratic statesman of Western orientation, Beneš relied heavily on the League of Nations as guarantor of the post war status quo and the security of newly formed states.

He negotiated the Little Entente (an alliance with Yugoslavia and Romania) in 1921 to counter Hungarian revanchism and Habsburg restoration.

Beneš ignored the possibility of a stronger Central European alliance system, remaining faithful to his Western policy.

In 1935, when Beneš succeeded Masaryk as president, the prime minister Milan Hodža took over the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

In the agricultural sector, a program of reform introduced soon after the establishment of the republic was intended to rectify the unequal distribution of land.

Land reform was to proceed on a gradual basis; owners would continue in possession in the interim, and compensation was offered.

[10] Furthermore, most of Czechoslovakia's industry was as well located in Bohemia and Moravia and there mainly in the German speaking Borderlands, while most of Slovakia's economy came from agriculture.

The German minority living in the Sudetenland demanded autonomy from the Czechoslovak government, claiming they were suppressed and repressed.