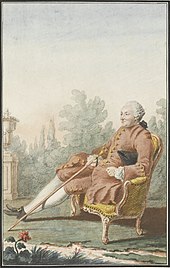

Baron d'Holbach

He helped in the dissemination of "Protestant and especially German thought", particularly in the field of the sciences,[1] but was best known for his atheism,[2] and for his voluminous writings against religion, the most famous of them being The System of Nature (1770) and The Universal Morality (1776).

[4] In 1750, he married his second cousin, Basile-Geneviève d'Aine (1728–1754), and in 1753 a son was born to them, Francois Nicholas, who left France before his father died.

The distraught d'Holbach moved to the provinces for a brief period with his friend Baron Grimm and in the following year received a special dispensation from the Pope to marry his deceased wife's sister, Charlotte-Suzanne d'Aine (1733–1814).

It is thought that the virtuous atheist Wolmar in Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse is based on d'Holbach.

[15] From c. 1750 to c. 1790, Baron d'Holbach used his wealth to maintain one of the more notable and lavish Parisian salons, which soon became an important meeting place for the contributors to the Encyclopédie.

Among the regulars in attendance at the salon—the coterie holbachique—were the following: Diderot, Grimm, Condillac, Condorcet, D'Alembert, Marmontel, Turgot, La Condamine, Raynal, Helvétius, Galiani, Morellet, Naigeon and, for a time, Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

[23] For the Encyclopédie d'Holbach authored and translated a large number of articles on topics ranging from politics and religion to chemistry and mineralogy.

Between 1751 and 1765, D'Holbach contributed some four hundred articles to the project, mostly on scientific subjects, in addition to serving as the editor of several volumes on natural philosophy.

[24] Despite his extensive contributions to the Encyclopédie, d'Holbach is better known today for his philosophical writings, all of which were published anonymously or under pseudonyms and printed outside France, usually in Amsterdam by Marc-Michel Rey.

Denying the existence of a deity, and refusing to admit as evidence all a priori arguments, d'Holbach saw the universe as nothing more than matter in motion, bound by inexorable natural laws of cause and effect.

[27] Regardless, however, of the extent of Diderot's contribution to the System of Nature, it is on the basis of this work that d'Holbach's philosophy has been called "the culmination of French materialism and atheism".

[28] D'Holbach's objectives in challenging religion were primarily moral: he saw the institutions of Christianity as a major obstacle to the improvement of society.

"[29] D'Holbach's radicalism posited that humans were fundamentally motivated by the pursuit of enlightened self-interest, which is what he meant by "society", rather than by empty and selfish gratification of purely individual needs.

Pleasure, riches, power, are objects worthy his ambition, deserving his most strenuous efforts, when he has learned how to employ them; when he has acquired the faculty of making them render his existence really more agreeable.

[31]The explicitly atheistic and materialistic The System of Nature presented a core of radical ideas which many contemporaries, both churchmen and philosophes found disturbing, and thus prompted a strong reaction.

The Catholic Church in France threatened the crown with withdrawal of financial support unless it effectively suppressed the circulation of the book.

The prominent Catholic theologian Nicolas-Sylvestre Bergier wrote a refutation titled Examen du matérialisme ("Materialism examined").

Voltaire hastily seized his pen to refute the philosophy of the Système in the article "Dieu" in his Dictionnaire philosophique, while Frederick the Great also drew up an answer to it.

Contrary to the revolutionary spirit of the time however, he called for the educated classes to reform the corrupt system of government and warned against revolution, democracy, and mob rule.

They also shared similar interests like gourmandizing, taking country walks and collecting fine prints, and beautiful paintings.

[38] When d'Holbach's radically atheistic and materialistic The System of Nature was first published, many believed Diderot to be the actual author of the book.

When the Abbé presented his work, he preceded it by reading his treatise on theatrical composition which the attendees at d'Holbach's found so absurd that they could not help being amused.

Suddenly he rose up like a madman and, springing towards the curé, took his manuscript, threw it on the floor, and cried to the appalled author, "Your play is worthless, your dissertation an absurdity, all these gentlemen are making fun of you.

According to Faguet, "d'Holbach, more than Voltaire, more than Diderot, is the father of all the philosophy and all the anti-religious polemics at the end of the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century.