DXing

Collecting these cards became popular with radio listeners in the 1920s and 1930s, and reception reports were often used by early broadcasters to gauge the effectiveness of their transmissions.

By the 1950s, and continuing through the mid-1970s, many of the most powerful North American "clear channel" stations such as KDKA, WLW, WGY, CKLW, CHUM, WABC, WJR, WLS, WKBW, KFI, KAAY, KSL and a host of border blasters from Mexico pumped out Top 40 music played by popular disc jockeys.

Outside of the Americas and Australia, most AM radio broadcasting was in the form of synchronous networks of government-operated stations, operating with hundreds, even thousands of kilowatts of power.

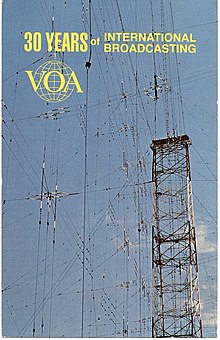

[4] Especially during wartime and times of conflict, reception of international broadcasters, whose signals propagate around the world on the shortwave bands has been popular with both casual listeners and DXing hobbyists.

Missionary religious broadcasters still make extensive use of shortwave radio to reach less developed countries around the world.

Many of these signals are transmitted in single side band mode, which requires the use of specialized receivers more suitable to DXing than to casual listening.

North American FM stations have been received in Western Europe,[6] and European TV signals have been received on the West Coast of the U.S.[7] Police, fire, and military communications on the VHF bands are also DX'ed to some extent on multi-band radio scanners, though they are mainly listened to strictly on a local basis.

On the VHF/UHF amateur bands, DX stations can be within the same country or continent, since making a long-distance VHF contact, without the help of a satellite, can be very difficult.

DXers collect QSL cards as proof of contact and can earn special certificates and awards from amateur radio organizations.

QSL cards often have a picture and messages indicating their country's culture or technological life on one side, and confirmation of the listeners reception data on the other.

The attributes are: S – Signal strength I – Interference with other stations or broadcasters N – Noise ratio in the received signal P – Propagation (ups and downs of the reception) O – Overall merit Reports are sent by post or email, and may include the listeners geographical location in longitude and latitude, the types of receiver and antennae used, the frequency the transmission was heard on, a brief description of the programme listened to, their opinion about it, and suggestions if any.

Ionospheric refraction is generally only feasible for frequencies below about 50 MHz, and is highly dependent upon atmospheric conditions, the time of day, and the eleven-year sunspot cycle.

Using just a simple AM radio, one can easily hear signals from the most powerful stations propagating hundreds of miles at night.

Enthusiasts utilize personal computers alongside radio control software tailored for FM reception, such as XDR-GTK, specifically designed for use with devices like the Sony XDR F1HD and NXP TEF668x-based receivers.

Additionally, tools like FM-DX Webserver, accessible directly through a web browser, further enhance the experience for FM & AM enthusiasts.