Daguerreotype

[5] To make the image, a daguerreotypist polished a sheet of silver-plated copper to a mirror finish; treated it with fumes that made its surface light-sensitive; exposed it in a camera for as long as was judged to be necessary, which could be as little as a few seconds for brightly sunlit subjects or much longer with less intense lighting; made the resulting latent image on it visible by fuming it with mercury vapor; removed its sensitivity to light by liquid chemical treatment; rinsed and dried it; and then sealed the easily marred result behind glass in a protective enclosure.

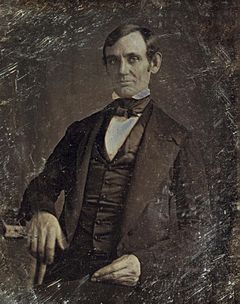

The image is on a mirror-like silver surface and will appear either positive or negative, depending on the angle at which it is viewed, how it is lit and whether a light or dark background is being reflected in the metal.

In the early 17th century, the Italian physician and chemist Angelo Sala wrote that powdered silver nitrate was blackened by the sun, but did not find any practical application of the phenomenon.

To copy these images was the first object of Mr. Wedgwood in his researches on the subject, and for this purpose he first used the nitrate of silver, which was mentioned to him by a friend, as a substance very sensible to the influence of light; but all his numerous experiments as to their primary end proved unsuccessful.

Niépce had invented an early internal combustion engine, (the Pyréolophore), together with his brother Claude and made improvements to the velocipede, as well as experimenting with lithography and related processes.

(indecipherable signature)The Treasury wrote to Miles Berry on 3 April to inform him of their decision: (To) Miles Berry Esq 66 Chancery Lane Sir, Having laid before the Lords &c your application on behalf of Messrs Daguerre & Niepce, that Government would purchase their Patent Right to the Invention known as the "Daguerreotype" I have it in command to acquaint you that Parliament has placed no Funds at the disposal of their Lordships from which a purchase of this description could be made 3rd April 1840 (signed) A. Gordon

He had started out experimenting with light-sensitive materials and had made a contact print from a drawing and then went on to successfully make the first photomechanical record of an image in a camera obscura – the world's first photograph.

[37] Jean-Baptiste Dumas, who was president of the National Society for the Encouragement of Science (Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale) and a chemist, put his laboratory at Daguerre's disposal.

[10][37] A paragraph tacked onto the end of a review of one of Daguerre's Diorama spectacles[38] in the Journal des artistes on 27 September 1835,[39] a Diorama painting of a landslide that occurred in "La Vallée de Goldau", made passing mention of rumour that was going around the Paris studios of Daguerre's attempts to make a visual record on metal plates of the fleeting image produced by the camera obscura: It is said that Daguerre has found the means to collect, on a plate prepared by him, the image produced by the camera obscura, in such a way that a portrait, a landscape, or any view, projected upon this plate by the ordinary camera obscura, leaves an imprint in light and shade there, and thus presents the most perfect of all drawings ... a preparation put over this image preserves it for an indefinite time ... the physical sciences have perhaps never presented a marvel comparable to this one.

[44] At a joint meeting of the French Academy of Sciences and the Académie des Beaux-Arts held at the Institut de Françe on Monday, 19 August 1839[45][46] François Arago briefly referred to the earlier process that Niépce had developed and Daguerre had helped to improve without mentioning them by name (the heliograph and the physautotype) in rather disparaging terms stressing their inconvenience and disadvantages such as that exposures were so long as eight hours that required a full day's exposure during which time the sun had moved across the sky removing all trace of halftones or modelling in round objects, and the photographic layer was apt to peel off in patches, while praising the daguerreotype in glowing terms.

Niépce's reputation as the real inventor of photography became known through his son Isidore's indignation that his father's early experiments had been overlooked or ignored although Nicéphore had revealed his process, which, at the time, was secret.

[57][61][62][63] By the late 18th century, small, easily portable box-form units equipped with a simple lens, an internal mirror, and a ground glass screen had become popular among affluent amateurs for making sketches of landscapes and architecture.

The camera was pointed at the scene and steadied, a sheet of thin paper was placed on top of the ground glass, then a pencil or pen could be used to trace over the image projected from within.

Daguerre, a skilled professional artist, was familiar with the camera obscura as an aid for establishing correct proportion and perspective, sometimes very useful when planning out the celebrated theatrical scene backdrops he painted and the even larger ultra-realistic panoramas he exhibited in his popular Diorama.

[70][71][72] In the Becquerel variation of the process, published in 1840 but very rarely used in the 19th century, the plate, sensitized by fuming with iodine alone, was developed by overall exposure to sunlight passing through yellow, amber or red glass.

Even when strengthened by gilding, the image surface was still very easily marred and air would tarnish the silver, so the finished plate was bound up with a protective cover glass and sealed with strips of paper soaked in gum arabic.

The more substantial Union case was made from a mixture of colored sawdust and shellac (the main component of wood varnish) formed in a heated mold to produce a decorative sculptural relief.

[79] As the daguerreotype itself is on a relatively thin sheet of soft metal, it was easily sheared down to sizes and shapes suited for mounting into lockets, as was done with miniature paintings.

[86] In the early 1840s, two innovations were introduced that dramatically shortened the required exposure times: a lens that produced a much brighter image in the camera, and a modification of the chemistry used to sensitize the plate.

Attempts at portrait photography with the Chevalier lens required the sitter to face into the sun for several minutes while trying to remain motionless and look pleasant, usually producing repulsive and unflattering results.

It was the first lens to be designed using mathematical computation, and a team of mathematicians whose specialty was in fact calculating the trajectories of ballistics was put at Petzval's disposal by the Archduke Ludwig.

[106][107] In one early attempt at portraiture, a Swedish amateur daguerreotypist caused his sitter nearly to lose an eye because of practically staring into the sun during the five-minute exposure.

In Britain, however, Richard Beard bought the British daguerreotype patent from Miles Berry in 1841 and closely controlled his investment, selling licenses throughout the country and prosecuting infringers.

[140] This method spread to other parts of the world as well: In 1839, François Arago had in his address to the French Chamber of Deputies outlined a wealth of possible applications including astronomy, and indeed the daguerreotype was still occasionally used for astronomical photography in the 1870s.

[146][147] Although the collodion wet plate process offered a cheaper and more convenient alternative for commercial portraiture and for other applications with shorter exposure times, when the transit of Venus was about to occur and observations were to be made from several sites on the earth's surface in order to calculate astronomical distances, daguerreotypy proved a more accurate method of making visual recordings through telescopes because it was a dry process with greater dimensional stability, whereas collodion glass plates were exposed wet and the image would become slightly distorted when the emulsion dried.

[148] A few first-generation daguerreotypists refused to entirely abandon their old medium when they started making the new, cheaper, easier to view but comparatively drab ambrotypes and tintypes.

[149] Historically minded photographers of subsequent generations, often fascinated by daguerreotypes, sometimes experimented with making their own or even revived the process commercially as a "retro" portraiture option for their clients.

[152] The daguerreotype experienced a minor renaissance in the late 20th century and the process is currently practiced by a handful of enthusiastic devotees; there are thought to be fewer than 100 worldwide (see list of artists on cdags.org in links below).

In recent years, artists like Jerry Spagnoli, Adam Fuss, Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand, Alyssa C. Salomon,[153] and Chuck Close have reintroduced the medium to the broader art world.

The appeal of the medium lies in the "magic mirror" effect of light striking the polished silver plate and revealing a silvery image which can seem ghostly and ethereal even while being perfectly sharp, and in the dedication and handcrafting required to make a daguerreotype.