Dan Donnelly (boxer)

[4] On the streets of Dublin, Donnelly had a reputation of being a hard man to provoke, but was known to be "handy with his fists", and he became the district's new fighting hero.

[5] There are a number of anecdotes about Donnelly's life in this period, including his rescue of a young woman being attacked by two sailors at the dockside, leading to his arm being badly mangled.

He was taken to the premises of the prominent surgeon Dr. Abraham Colles who saved Donnelly's arm from amputation, describing him as a "pocket Hercules".

[7] News of his fighting exploits with Dublin's feuding gangs spread swiftly,[8] and he gained a reputation for keeping local criminals in check.

One boxer, recognized as champion of the city, became jealous of Donnelly's reputation and took to following him around the local taverns demanding a fight.

Right up to the time they took sparring positions, Donnelly tried to talk his rival out of fighting, but his pleas fell on deaf ears.

As the fight dragged on, Donnelly gradually overcame his rival, and in a furious attack in the 16th round, beat him to the ground.

Captain William Kelly listened as a pair of English prize-fighters mocked Ireland's reputation as a nation of courageous men.

Donnelly's first big fight under the patronage of Captain Kelly, was staged at the Curragh in County Kildare on 14 September 1814.

Donnelly's opponent was a prominent English fighter, Tom Hall, who was touring Ireland, giving sparring exhibitions and boxing instruction.

By one o'clock when the bout was due to start, an estimated 20,000 people[1] packed onto the sides of the hollow, at the base of which a 22-foot (6.71 m) square had been roped off.

Eventually he did lose his temper, and as Hall slipped down yet again, Donnelly lashed out and hit him on the ear; the blood flowed.

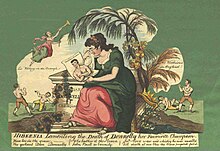

In the minds of the populace, Dan Donnelly epitomized the national struggle in an Ireland governed by mad old George III, championing their seemingly hopeless cause against the intransigent representatives of the Crown.

The political climate between Ireland and Britain is better and more peaceful today than it has been in a very long time, but if a rugby or soccer game is held between the two countries, there is a certain amount of tension or jingoism.

A competitor gets, more or less, in front of his opponent, and throws his adversary over his hip, causing him to land with great force on the ground.

[25] If one popular story is to be believed, Donnelly, who was being badly beaten in the fifth round, was saved by the magical properties of a lump of sugar cane slipped to him by Captain Kelly's sister.

When Donnelly failed to respond, she slipped him a piece of the sugar cane, while urging him, "Now my charmer, give him a warmer!

As Donnelly proudly strode up the hill towards his carriage, fanatical followers dug out imprints left by his feet.

[28] Leading from the monument which commemorates the scene of his greatest victory, "The Steps to Strength and Fame" are still to be seen in Donnelly's Hollow.

Donnelly became a publican, hoping his notoriety would entice extra customers eager to hear stirring tales of his prize-ring.

In his third and final fight on 21 July 1819, he defeated Tom Oliver in 34 rounds on English turf, at Crawley Down in Sussex.

Egan irately described the reception accorded to Donnelly during a benefit night (6 April 1819) as 'rather foul': 'It was very unlike the usual generosity of John Bull towards a stranger – It was not national – but savoured something like prejudice' (Boxiana, vol.

[29] This animosity was borne predominantly from concern over the Irishman's fighting prowess, and Egan underscored the combination of resentment and overwhelming interest when reporting Donnelly's fight with Oliver: 'The English amateurs viewed him as a powerful opponent [and...] jealous for the reputation of the "Prize Ring", clenched their fists in opposition, whenever his growing fame was chaunted' (Boxiana, vol.

A squat, weather-beaten, gray obelisk surrounded by a short iron fence marks the exact site of the Cooper bout.

The date inscribed was inaccurate, as the bout actually took place one month earlier, on 13 November 1815, as reported in the Freeman's Journal the following day.

[31] After just a few nights, grave robbers put Donnelly's body in a sack and delivered him to an eminent surgeon who paid good money for cadavers for study.

George Cooper and Dan Donnelly, as played by McCourt and Berney, had a group of supporters as well, dressed up and cheering, carrying them down into the arena.

After the media search gained traction, Josephine revealed that they kept the arm during the sale and it was disrespectfully laying in their basement.

Josephine didn't care about the human limb that was almost 200 years old and wanted to stow it in the cargo hold for transportation to America.

[45] As the centerpiece of the Fighting Irishmen Exhibit, Donnelly's arm went on display at the Irish Arts Center in New York City, in the autumn of 2006.