Daniel McCallum

[3] In the early 1840s, McCallum worked as a civil engineer in Rochester, designing buildings including Saint Joseph's Church.

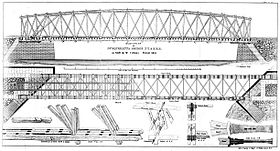

[4] By the late 1840s, the New York and Erie Railroad placed McCallum in charge of its bridges,[5] and he started experimenting with new construction methods.

[2] About two years later (1854/54) he received another promotion, becoming the railroad's General Superintendent and succeeding Charles Minot during Homer Ramsdell's presidency.

[8] On February 11, 1862, weeks after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Railways and Telegraph Act of January 31, 1862 (which authorized the president to seize and operate any railroad or telegraph company's equipment for use during the American Civil War), the new secretary of war Edwin M. Stanton appointed McCallum as military director and superintendent of the United States Military Railroad with the staff rank of colonel.

On May 28 Haupt was also appointed a colonel, but he twice refused military rank (including a promotion to brigadier general on September 5, 1862), instead of becoming the civilian Chief of Construction and Transportation in the Department of the Rappahannock.

[10] McCallum remained in Washington during the war to oversee the "big picture" of USMRR operations, and especially coordinate deliveries of locomotives and other equipment with manufacturers.

He received a brevet promotion to brigadier-general of volunteers for faithful and meritorious services on September 24, 1864, and his authority was extended to the Western Theater and to support Sherman's Atlanta Campaign.

[12] The most famous was called 'Lights on the Bridge', which he wrote shortly before his death, memorializing his friend, Sam Campbell, a railroad engineer killed in 1842.

In this plan of Mr. McCallum, the two principles are not independent as heretofore; but the action of the arch in the upper chord is made an integral part of the truss itself; and instead of two systems acting unequally, and to the ultimate injury of the structure, we have the best features of both united in a manner which admits of entire uniformity of action.In the construction of bridges for railroad purposes, two prominent difficulties have long been discovered, viz., a lack of sustaining principle towards the ends of the trusses and near the abutments, and an entire absence in many cases of a proper counteracting principle to prevent vertical vibration by a moving load.

[18] Some of the Howe truss men were so impressed by McCallum's business success (if not by his arguments) that they began arching their top chords, and a notable example of this practice was the Rock Island Bridge over the Mississippi River.

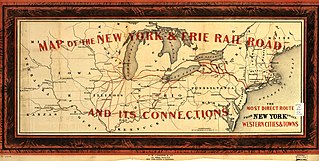

In his 1856 report to the stockholders of the New York & Erie Railroad he explained: "A superintendent of a road fifty miles in length can give it's business his professional attention and may be constantly on the line engaged in the direction of its details; each person is personally known to him, and all questions in relation to its business are at once presented and acted upon, and any system however imperfect may under such circumstances prove comparatively successful.

and I am fully convinced that in the want of system perfect in its details, properly adapted and vigilantly enforced, lies the true secret of their [the large roads’] failure; and that this disparity of cost per mile in operating long and short roads, is not produced by a difference in length, but is in proportion to the perfection of the system adopted..."[21]New methods had to be invented for mobilizing, controlling, and apportioning capital, for operating a widely dispersed system, and for supervising thousands of specialized workmen spread over hundreds of miles.

The main innovators were three engineers, Benjamin H. Latrobe of the Baltimore and Ohio, McCallum of the Erie, and John Edgar Thomson of the Pennsylvania (railroad).

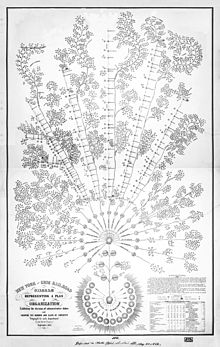

On the chart is written,[23] that the diagram represents a plan of organization, and exhibits the division of administrative duties and shows the number and class of employees engaged in each department, and is dated September 1855.

The chart explains that the diagram is compiled from the latest monthly report and indicates the average number of employees of each class engaged in the Operating Department of the railroad company.

In his 1856 report he formulated the following requirements:[27] McCallum presented the following general principles for the formation of such an efficient system of operations,[28] reprinted in Vose (1857)[29] About the core principle of management, he summarized:[30] "All that is required to render the efforts of railroad companies in every respect equal to that of individuals, is a rigid system of personal accountability through every grade of service..."Vose (1857, p. 416) added, that all subordinates should be accountable to, and directed by, their immediate superiors only.

Each officer must have authority, with the approval of the general superintendent, to appoint all persons for whose acts he is held responsible, and to dismiss any subordinate when in his judgment the interests of the company demand it.

[29] On 11 February 1862, McCallum was appointed military director and superintendent of the Union railroads, with the staff rank of colonel, by Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War.

At the time that McCallum assumed his duties, the seven-mile road from Washington to Alexandria, Virginia, was the only railroad in federal government control.

No person was allowed to be transported on the cars except those authorized by the War Department, and the train never moved at speeds of more than 20 miles (32 km) an hour to avoid any accidents.

Of the firms alluded to, one of the most eminent is that of Mr. D. C. McCallum, an Engineer of high standing, who was for several years the manager of the New York and Erie Railway, a length of 460 miles, exclusive of branches.

The first mention [in Great Britain] of this bridge, and of Mr. McCallum's admirable system of working trains by the electric telegraph, will be found in Captain Galton's Report on the Railways of the United States..."[33]The National Cyclopedia of American Biography (1897) confirmed, that the inflexible arched truss introduced by McCallum has probably been in more general use in the United States than any other system of timber bridges.

Nor does Sidney Pollard in his "Genesis of Modern Management" note any discussion about the nature of major principles of organization occurring in Great Britain before the 1830s, the data at which he stops his analysis..."[39]McCallum's work drew national and international attention.

Douglas Galton, one of Britain's leading railroad experts, described McCallum's work in a parliamentary report printed in 1857.