Dante Symphony

Written in the high romantic style, it is based on Dante Alighieri's journey through Hell and Purgatory, as depicted in The Divine Comedy.

At this early stage in the composition, it was Liszt's intention that performances of the work be accompanied by a slideshow depicting scenes from the Divine Comedy by the artist Bonaventura Genelli.

In his autobiography, he later wrote: If anything had convinced me of the man's masterly and poetical powers of conception, it was the original ending of the Faust Symphony, in which the delicate fragrance of a last reminiscence of Gretchen overpowers everything, without arresting the attention by a violent disturbance.

I was the more startled to hear this beautiful suggestion suddenly interrupted in an alarming way by a pompous, plagal cadence which, as I was told, was supposed to represent St Dominic.

"[10]Liszt agreed and explained that such had been his original intention, but he had been persuaded by Princess Carolyne to end the symphony in a blaze of glory.

He rewrote the concluding measures, but in the printed score, he left the conductor with the option of following the pianissimo coda with the fortissimo one.

This action, some critics claim, effectively destroyed the work's balance, leaving the listener, like Dante, gazing upward at the heights of Heaven and hearing its music from afar.

[16] Nevertheless, he persevered with the work, conducting another performance (along with his symphonic poem Die Ideale and his second piano concerto) in Prague on 11 March, 1858.

[17] Like his symphonic poems Tasso and Les préludes, the Dante Symphony is an innovatory work, featuring numerous orchestral and harmonic advances: wind effects, progressive harmonies that generally avoid the tonic-dominant bias of contemporary music, experiments in atonality, unusual key signatures and time signatures, fluctuating tempi, chamber-music interludes, and the use of unusual musical forms.

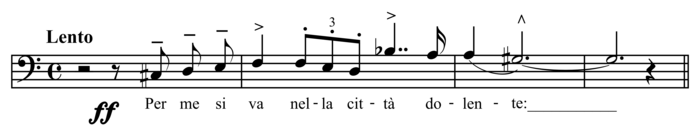

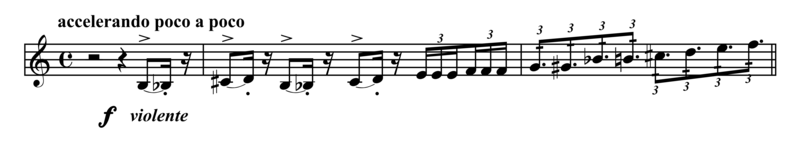

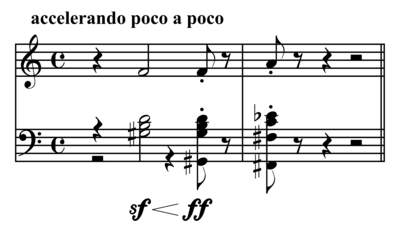

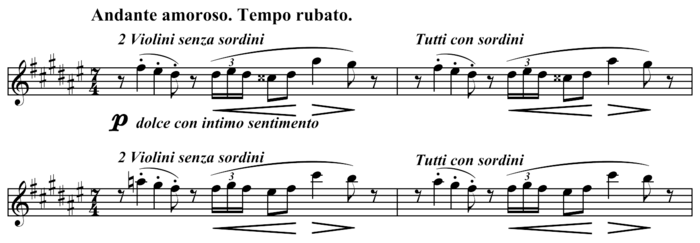

9 The first of these themes, which is immediately repeated in a slightly varied form, begins in D minor – a key Liszt associated with Hell[23] – but ends ambiguously on G♯ a tritone higher.

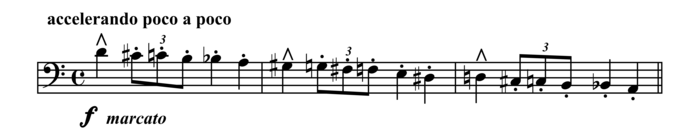

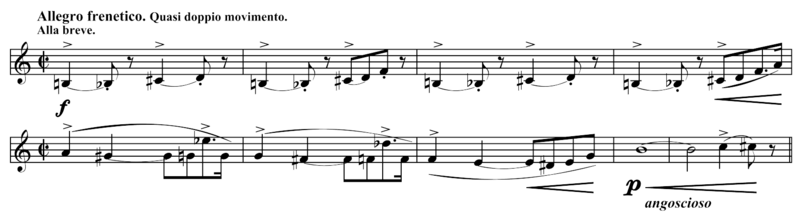

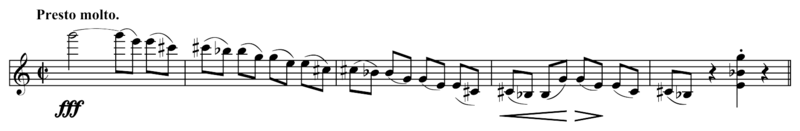

Ostensibly it begins in D minor, but the tonality is ambiguous: The tempo increases to Presto molto and a second subject is played by wind and strings over a pedal on the dominant A: Although Liszt provides no verbal clues to the literary associations of these themes, it seems reasonable to assume that the exposition and ensuing section represent the Vestibule (in which the dead are condemned to perpetually chase after a whirling standard) and First Circle of Hell (Limbo), which Dante and Virgil traverse after they have passed through the Gates of Hell.

[citation needed] It is even possible that the transition between the two subjects represents the river Acheron, which separates the Vestibule from the First Circle: on paper the figurations are reminiscent of those Beethoven uses in the Scene by the Brook in his Pastoral Symphony, though the aural effect is quite different.

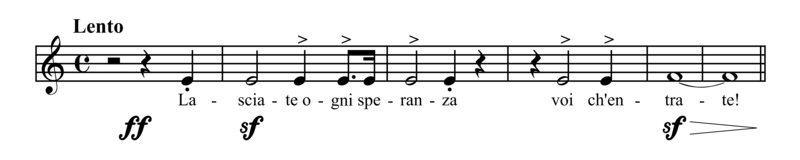

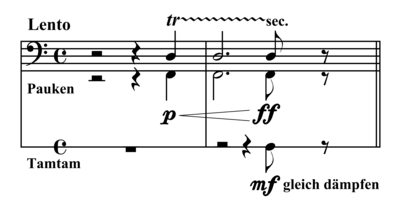

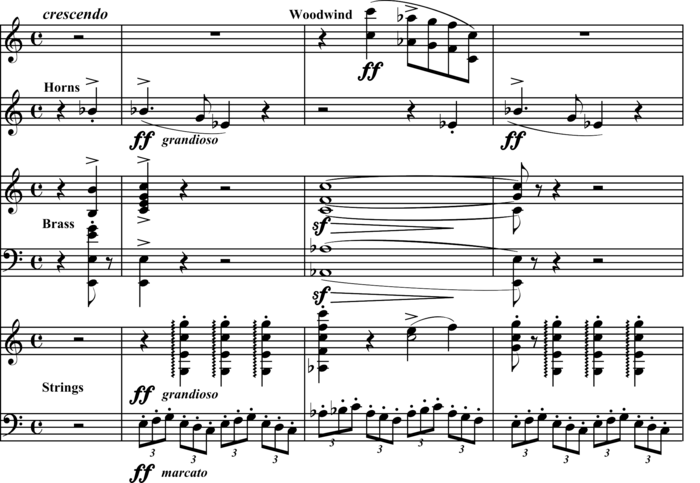

The music reaches a great climax (molto fortissimo); the tempo reverts to the opening Lento, and the brass intone the Lasciate ogni speranza theme from the slow introduction, accompanied by the drum-roll motif.

As Dante and Virgil enter the Second Circle of Hell, rising and falling chromatic scales in the strings and flutes conjure up the infernal Black Wind that perpetually buffets the damned.

An episode in 54 time marked Quasi Andante, ma sempre un poco mosso ensues, beginning with harp glissandi and chromatic figurations in strings and woodwind that once again invoke the swirling wind.

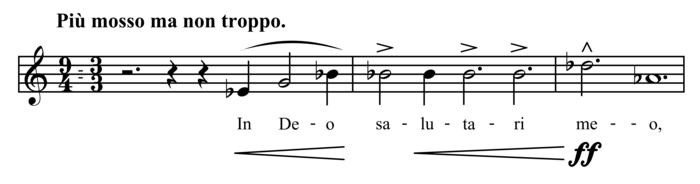

After a restatement a fourth higher by the bass clarinet, the recitative is played by the cor anglais and this time Liszt sets the music to the words of Francesca da Rimini, whose adulterous affair with her brother-in-law Paolo cost her both her life and her soul: .... Nessun maggior dolore che ricordarsi del tempo felice ne la miseria.

In the final ten measures, however, the Lasciate ogni speranza theme returns for the last time: Dante and Virgil emerge from Hell on the other side of the world.

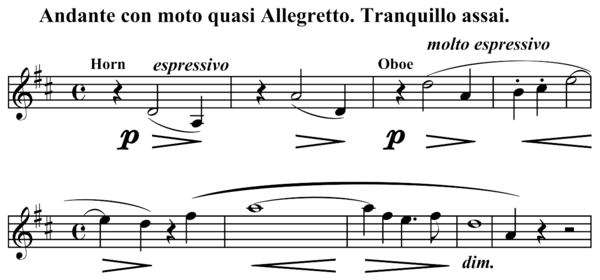

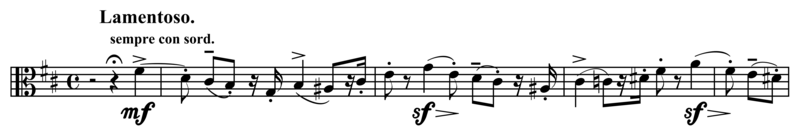

A solo horn introduces the opening theme to the accompaniment of rocking chords on muted strings and arpeggiated triplets played by the harp.

This theme is taken up by the woodwind and horns, and after twenty-one measures dies away against a shimmering haze of rising and falling arpeggios on the harp: This whole section is then repeated in E♭ (though the key signature is altered from D major to B♭.

In Canto 7 there is a celebrated description of evening in a beautiful valley where the penitents sing the Salve Regina; this passage may have inspired Liszt's chorale-like theme.

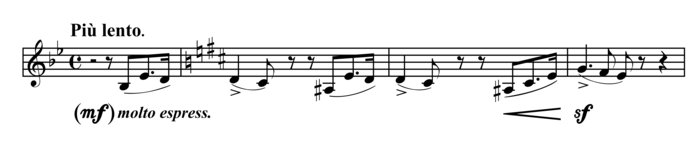

The music graphically reflects the pleading and suffering of the penitents before it breaks up into flowing triplets:[34] This theme is taken up by the other strings and a five-part fugue ensues.

A brief transition ensues in which staccato triplets in the cellos and double basses are answered by static chords in the stopped horns and woodwind.

The triplets, now played legato on the violins, are accompanied by passionate figures in the woodwind (gemendo, dolente ed appassionato) and muted chords in the horns.

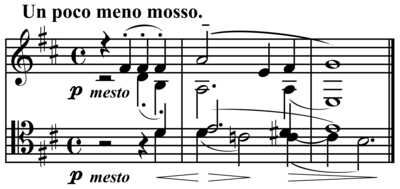

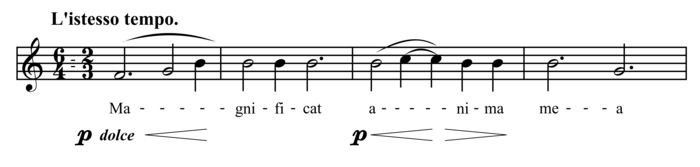

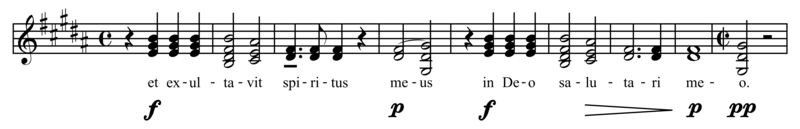

The choir intones the words against a shimmering backdrop of divided strings, rocking figurations in the woodwind and arpeggios played by two harps.

The tempo quickens and the music becomes gradually louder as the time signature changes to 94 (= 33, i.e. each bar is divided into three dotted half notes).

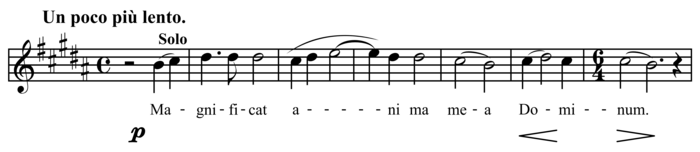

After another brief silence, the choir sings a chorale to the second line of the Magnificat, accompanied by a solo cello, bassoons and clarinets.

In the triumphant coda, the divided chorus sings Hosanna and Hallelujah in a series of carefully crafted modulations, which reflect Dante's ascent sphere-by-sphere towards the Empyrean; this is in marked contrast to the first movement, where key shifts were sudden and disjointed.

Liszt was proud of this innovatory use of the whole-tone scale, and mentions it in a letter to Julius Schäffer, the music director of the Schwerin orchestra.

George Bernard Shaw, reviewing the work in 1885, criticized it heavily, complaining that the manner in which the programme was presented by Liszt could just as well represent "a London house when the kitchen chimney is on fire".

[40] On the other hand, James Huneker called the work "the summit of [Liszt's] creative power and the ripest fruit of that style of programme music".