Dark matter halo

[1] Modern cosmological models, such as ΛCDM, propose that dark matter halos and subhalos may contain galaxies.

Their existence is inferred through observations of their effects on the motions of stars and gas in galaxies and gravitational lensing.

[3] Dark matter halos play a key role in current models of galaxy formation and evolution.

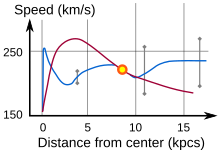

[4][5][6][7] The presence of dark matter (DM) in the halo is inferred from its gravitational effect on a spiral galaxy's rotation curve.

Without large amounts of mass throughout the (roughly spherical) halo, the rotational velocity of the galaxy would decrease at large distances from the galactic center, just as the orbital speeds of the outer planets decrease with distance from the Sun.

Freeman noticed that the expected decline in velocity was not present in NGC 300 nor M33, and considered an undetected mass to explain it.

During initial galactic formation, the temperature of the baryonic matter should have still been much too high for it to form gravitationally self-bound objects, thus requiring the prior formation of dark matter structure to add additional gravitational interactions.

The current hypothesis for this is based on cold dark matter (CDM) and its formation into structure early in the universe.

As time proceeds, small-scale perturbations grow and collapse to form small halos.

Once these subhalos formed, their gravitational interaction with baryonic matter is enough to overcome the thermal energy, and allow it to collapse into the first stars and galaxies.

However, it cannot be a complete description, as the enclosed mass fails to converge to a finite value as the radius tends to infinity.

[18] Numerical simulations of structure formation in an expanding universe lead to the empirical NFW (Navarro–Frenk–White) profile:[19] where

Higher resolution computer simulations are better described by the Einasto profile:[21] where r is the spatial (i.e., not projected) radius.

Even the earliest simulations of structure formation in a CDM universe emphasized that the halos are substantially flattened.

[23] Subsequent work has shown that halo equidensity surfaces can be described by ellipsoids characterized by the lengths of their axes.

With increasing computing power and better algorithms, it became possible to use greater numbers of particles and obtain better resolution.

In addition the orbit itself evolves as the subhalo is subjected to dynamical friction which causes it to lose energy and angular momentum to the dark matter particles of its host.

Whether a subhalo survives as a self-bound entity depends on its mass, density profile, and its orbit.

[18] As originally pointed out by Hoyle[28] and first demonstrated using numerical simulations by Efstathiou & Jones,[29] asymmetric collapse in an expanding universe produces objects with significant angular momentum.

Numerical simulations have shown that the spin parameter distribution for halos formed by dissipation-less hierarchical clustering is well fit by a log-normal distribution, the median and width of which depend only weakly on halo mass, redshift, and cosmology:[30] with

[31] The visible disk of the Milky Way Galaxy is thought to be embedded in a much larger, roughly spherical halo of dark matter.

[32][33] A 2014 Jeans analysis of stellar motions calculated the dark matter density (at the sun's distance from the galactic centre) = 0.0088 (+0.0024 −0.0018) solar masses/parsec^3.