David Hicks

There was widespread Australian and international criticism and political controversy over Hicks' treatment, the evidence tendered against him, his trial outcome, and the newly created legal system under which he was prosecuted.

[17][18][3] In October 2012, the United States Court of Appeals ruled that the charge under which Hicks had been convicted was invalid because the law did not exist at the time of the alleged offence, and it could not be applied retroactively.

[15][16] The following month, in accordance with a pre-trial agreement struck with convening authority Judge Susan J. Crawford, Hicks entered an Alford plea to a single newly codified charge of providing material support for terrorism.

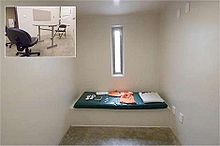

Hicks's legal team attributed his acceptance of the plea bargain to his "desperation for release from Guantanamo" and duress under "instances of severe beatings, sleep deprivation and other conditions of detention that contravene international human rights norms."

[30] Colonel Morris Davis, the former Pentagon chief prosecutor, later confessed political interference in the case by the Bush administration in the United States and the Howard government in Australia.

He took extensive notes on, and made sketches of, various weaponry mechanisms and attack strategies (including Heckler & Koch submachine guns, the M16 assault rifle, RPG-7 grenade launcher, anti-tank rockets, and VIP security infiltration).

How would a white boy new to Islam, not understanding local customs or languages, largely uneducated in the ways of the world, get access to such supposedly secret camps planning acts of terror?

[49] In a memoir that was later repudiated by its author, the Guantanamo detainee Feroz Abbasi claimed Hicks was "Al-Qaedah's 24 [carat] Golden Boy" and "obviously the favourite recruit" of their al-Qaeda trainers during exercises at the al-Farouq camp near Kandahar.

[6] A US Department of Defense statement claimed that "viewing TV news coverage in Pakistan of the 11 September 2001 attacks against the United States" led Hicks to return to Afghanistan to "rejoin his al-Qaeda associates to fight against U.S., British, Canadian, Australian, Afghan, and other coalition forces.

[39][42] Hicks arrived in the southern Afghan city of Kandahar where he reported to Saif al Adel, who was assigning individuals to locations, and "armed himself with an AK-47 automatic rifle, ammunition, and grenades to fight against coalition forces."

After guarding the tank for a week, Hicks, with an L-e-T acquaintance, travelled closer to the battle front in Kunduz where he joined others, including John Walker Lindh.

[28][42] Colonel Morris Davis, chief prosecutor for the US office of Military Commissions, said, "He eventually left Afghanistan and it's my understanding was heading back to Australia when 9/11 happened.

The indictment made the following allegations: On 29 June 2006, the US Supreme Court ruled in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld that the military commissions were illegal under United States law and the Geneva Conventions.

In an interview with The Age newspaper in January 2007, Col. Morris Davis, the chief prosecutor in the Guantanamo military commissions, also alleged that Hicks had been issued with weapons to fight US troops, and had conducted surveillance against US and international embassies.

On 7 July 2006, a memo was issued from The Pentagon directing that all military detainees are entitled to humane treatment and to certain basic legal standards, as required by Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions.

[82] On 15 August 2006, Attorney-General Philip Ruddock announced that he would seek to return Hicks to Australia if the United States did not proceed quickly to lay substantive new charges.

[83] As a result of the Supreme Court decision, the United States Congress passed the Military Commissions Act of 2006 to provide an alternative method for trying detainees held at Guantanamo Bay.

On 13 December 2005, Lord Justice Lawrence Collins of the High Court ruled that then-Home Secretary Charles Clarke had "no power in law" to deprive Mr Hicks of British citizenship "and so he must be registered".

The Home Office announced it would take the matter to the Court of Appeal, but Justice Collins denied them a stay of judgement, meaning that the British government must proceed with the application.

[95] On 17 March 2006 the Home Office alleged during its appeal case that Hicks had admitted in 2003 to the Security Service (British intelligence agency MI5) that he had undergone extensive terrorist training in Afghanistan.

Described as a security measure, it was claimed that instructions for tying a hangman's noose had been found written on stationery issued to the lawyers who met with detainees to discuss their habeas corpus requests.

[114] Leaders and legal commentators in both countries criticised the prosecution as the application of ex post facto law and deemed the 5-year process to be a violation of Hicks's basic rights.

[124] The agreement stipulated that Hicks enter an Alford plea to a single charge of providing material support for terrorism in return for a guarantee of a much shorter sentence than had been previously sought by the prosecution.

[125][126][127][128][129][130][131][132][133][134] The length of the sentence caused an "outcry" in the United States and against Defense Department lawyer Susan Crawford, who allegedly bypassed the prosecution in order to meet an agreement with the defence made before the trial.

[138] In an interview, the prominent human rights lawyer and UN war crimes judge Geoffrey Robertson QC said that the pre-trial agreement "was obviously an expedient at the request of an Australian Government that needed to shore up votes".

[166] In October 2012, the United States Court of Appeals ruled that the charge under which Hicks had been convicted was invalid, because the law did not exist at the time of the alleged offence, and it could not be applied retrospectively.

However, Raymond Bonner, writing in the Pacific Standard, reported that Martins's reply made the "crucial concession" that "if the appeal were allowed, 'the Court should not confirm Hicks's material-support conviction.'"

At the time of publication, Nikki Christer, a spokesperson for Random House, refused to comment whether Hicks was being paid for the book or whether the publisher or the author are at risk of falling foul of federal proceeds of crime laws.

[172] ABC News quoted George Williams, a legal expert from the University of New South Wales, who said "You can't proceed unless you actually know that Hicks is profiting.

Hicks' legal team argued that they were made under "instances of severe beatings, sleep deprivation and other conditions of detention that contravene international human rights norms.