David J. Brewer

Brewer opposed governmental interference in the free market and rejected the Supreme Court's decision in Munn v. Illinois (1877), which had upheld the states' power to regulate businesses, writing: "The paternal theory of government is to me odious."

Off the bench, he was a prolific public speaker who decried Progressive reforms and criticized President Theodore Roosevelt; he also advocated for peace and served on an arbitral commission that resolved a boundary dispute between Venezuela and the United Kingdom.

[6]: 618 Brewer expressed interest in politics during his college years, and he wrote numerous forceful letters to the editor, including a fiery denunciation of the Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision.

[1]: 53 As a circuit judge, he heard a wide variety of cases, including federal civil disputes, matters arising under the court's diversity jurisdiction, and the occasional criminal prosecution.

[1]: 56 In State v. Walruff,[g] Brewer firmly reiterated the position that he had expressed in Mugler, appealing to "the guarantees of safety and protection to private property"[4]: 1518 to rule that the Fourteenth Amendment required Kansas to compensate beer manufacturers affected by prohibition laws.

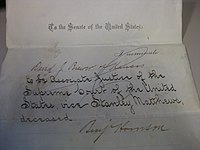

[15]: 360–362 Other candidates suggested to Harrison included the Detroit attorney Alfred Russell, whom Vice President Levi P. Morton endorsed, and McCrary, who was favored by many Midwestern politicians and jurists.

[1]: 74 Prohibitionists, maintaining that Brewer's opinion in Walruff was "conclusive proof of what we already fear—the total surrender to the liquor dealers of the country", expressed opposition, but the selection was otherwise viewed favorably.

[1]: 74–75 The full Senate, in a secret session that The New York Times characterized as "absurd", heard prolonged speeches from several members who opposed the nominee on the grounds that he was hostile to prohibition or partial toward the railroad interests.

[17]: 578 While accepting that "Brewer can fairly be labeled a conservative", the legal scholar J. Gordon Hylton wrote in 1994 that "to say that he was a self-conscious defender of the interests of corporate America or an enthusiastic disciple of laissez-faire is both unfair and inaccurate".

[22]: 213 According to the legal scholar Owen M. Fiss, Brewer and his "constant ally" Rufus W. Peckham[23]: 55 were the "intellectual leaders" of the Fuller Court—justices who, while not always in the majority, were "influential within the dominant coalition and the source of the ideas that gave the Court its sweep and direction".

[12]: 202 Brewer supported states' rights and felt that the judiciary should limit governmental actions that interfere with the free market, although the legal historian Kermit L. Hall writes that his jurisprudence "was not altogether predictable" because "[h]is Congregational, missionary, and anti-slavery roots" gave him "a sympathetic ear for the disadvantaged".

[20]: 69–70 Brewer and his fellow conservative justices led the Court toward rulings that interpreted the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments broadly to protect property rights from various regulations.

[4]: 1523 [25]: 108 The decision, which endorsed the idea that the Due Process Clause contained a substantive component that limited state regulatory authority, was at odds with the Court's holding in Munn that rate-setting was a matter for legislators, not judges, to decide.

[26]: 85 Strenuously dissenting in Budd v. New York,[i] Brewer derided Munn as "radically unsound"[25]: 111 and, using a phrase that according to Brodhead "has ever since linked his name to opposition to reform", wrote: "The paternal theory of government is to me odious.

"[1]: 86 His opinion for a unanimous Court in Reagan v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. built on the Chicago, Milwaukee decision, curtailing Munn and asserting that the judiciary could review the reasonableness of railroad rates.

[29]: 588–589 Brewer joined the Court's opinion, which was written by Peckham; it maintained that due process included a right to enter labor contracts without being subject to unreasonable governmental regulation.

[31]: 219–220 In an opinion that has been condemned as patronizing toward women, Brewer argued that Oregon's law was different from the one at issue in Lochner because female workers were in special need of protection due to their "physical structure and the performance of maternal functions", which put them "at a disadvantage in the struggle for subsistence".

[17]: 586 Brewer joined the majority in the case of Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.,[o] a decision that, according to Brodhead, "contributed much to [the Fuller Court's] reputation for favoritism toward corporate and other forms of wealth".

[1]: 95–96 ) The Pollock decision, which was in effect overruled by the Sixteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, has conventionally been condemned as unfaithful to precedent, at odds with public opinion, and protective of the interests of the rich.

[20]: 71 In a brief concurrence that according to the legal scholar John E. Semonche "illustrates his integrity, competence, and sophistication" better than any of his other opinions, Brewer expressed support for property rights but concluded that the proposed merger was an unlawful attempt to suppress competition.

[37]: 1056–1057 Brewer's opinion in Holy Trinity also contained a statement that, according to the legal scholar William M. Wiecek, "would be unthinkable today" from a Supreme Court justice:[2]: 181 that the United States "is a Christian nation".

[38]: 232 He cited religious elements of historical documents, court decisions, and "American life as expressed by its laws, its business, its customs and its society" in support of his thesis that Congress could not have intended to bar clergymen from the country.

[26]: 159 In an opinion that stood in conspicuous conflict with his ordinary support for property rights, Brewer (over Harlan's dissent) rejected that argument, concluding that states had the ability to amend corporate charters.

[17]: 320–321 Although Brewer did not cast a vote in the landmark case of Plessy v. Ferguson[ac]—he had returned home to Kansas due to the death of his daughter—Paul states that he undoubtedly would have joined the majority opinion upholding "separate but equal" segregation laws had he been present.

[39]: 90 In Fong Yue Ting v. United States,[ad] he vigorously dissented when the Court ruled that Chinese non-citizens could be deported without being provided with due process, decrying the majority's understanding of the federal government's powers as "indefinite and dangerous".

[25]: 119, 131 In another Insular Case, Downes v. Bidwell,[aj] Brewer joined Fuller's dissent when the Court upheld a provision of the Foraker Act that imposed an otherwise-unconstitutional tariff on Puerto Rico.

[31]: 140 Although Brewer did not write an opinion in any of the Insular Cases, he held strong views on the matters they presented: he opposed imperialism in public remarks and wrote a letter to Fuller urging him to "stay on the court till we overthrow this unconstitutional idea of colonial supreme control".

[3]: 97–98 According to the historian Linda Przybyszewski, Brewer was "probably the most widely read jurist in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century" due to what Justice Holmes characterized as his "itch for public speaking".

[17]: 572 In his later years, he spoke increasingly on political topics: he decried Progressive reforms and inveighed against President Theodore Roosevelt, who in turn loathed Brewer and stated in private that he had "a sweetbread for a brain" and was a "menace to the welfare of the Nation".

[39]: 89 Moreover, although public sentiment regarding the justice was mixed in the years following his death, he was almost never discussed favorably after the 1930s, being generally described as an ultra-conservative who adhered closely to laissez-faire principles and made the courts subservient to corporations.