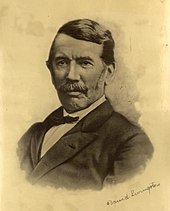

David Livingstone

[3] Livingstone came to have a mythic status that operated on a number of interconnected levels: Protestant missionary martyr, working-class "rags-to-riches" inspirational story, scientific investigator and explorer, imperial reformer, anti-slavery crusader, and advocate of British commercial and colonial expansion.

[5] Livingstone was born on 19 March 1813 in the mill town of Blantyre, Scotland, in a tenement building for the workers of a cotton factory on the banks of the River Clyde under the bridge crossing into Bothwell.

[7] In 1832, he read Philosophy of a Future State, written by Thomas Dick, and he found the rationale that he needed to reconcile faith and science and, apart from the Bible, this book was perhaps his greatest philosophical influence.

Influenced by revivalistic teachings in the United States, Livingstone entirely accepted the proposition put by Charles Finney, Professor of Theology at Oberlin College, Ohio, that "the Holy Spirit is open to all who ask it".

[9] Livingstone's reading of missionary Karl Gützlaff's Appeal to the Churches of Britain and America on behalf of China enabled him to persuade his father that medical study could advance religious ends.

His father was persuaded and, like many other students in Scotland, Livingstone was to support himself, with the agreement of the mill management, by working at his old job from Easter to October, outwith term time.

[11][12][13] To enter medical school, he needed some knowledge of Latin, and was tutored by a local Roman Catholic man, Daniel Gallagher (later a priest, founder of St Simon's, Partick).

He was then accepted as a probationary candidate, and given initial training at Ongar, Essex, as the introduction to studies to become a minister within the Congregational Union serving under the LMS, rather than the more basic course for an artisan missionary.

At Ongar, he and six other students had tuition in Greek, Latin, Hebrew and theology from the Reverend Richard Cecil, who in January 1839 assessed that, despite "heaviness of manner" and "rusticity", Livingstone had "sense and quiet vigour", good temper and substantial character "so I do not like the thought of him being rejected."

At Rio de Janeiro, unlike the other two, he ventured ashore and was impressed by the cathedral and scenery, but not by drunkenness of British and American sailors so he gave them tracts in a dockside bar.

From September to late December he trekked 750 miles (1,210 km) with the artisan missionary Roger Edwards, who had been at Kuruman since 1830 and had been told by Moffat to investigate potential for a new station.

[33] Livingstone was obliged to leave his first mission at Mabotsa in Botswana in 1845 after irreconcilable differences emerged between him and his fellow missionary, Rogers Edwards, and because the Bakgatla were proving indifferent to the Gospel.

[35] To improve his Tswana language skills and find locations to set up mission stations, Livingstone made journeys far to the north of Kolobeng with William Cotton Oswell.

His motto—now inscribed on his statue at Victoria Falls—was "Christianity, Commerce and Civilization", a combination that he hoped would form an alternative to the slave trade, and impart dignity to the Africans in the eyes of Europeans.

When Roderick Murchison, president of the Royal Geographical Society, put him in touch with the foreign secretary, Livingstone said nothing to the LMS directors, even when his leadership of a government expedition to the Zambezi seemed increasingly likely to be funded by the exchequer.

Livingstone had envisaged another solo journey with African helpers, in January 1858 he agreed to lead a second Zambezi expedition with six specialist officers, hurriedly recruited in the UK.

On 10 January 1863 they set off, towing Lady Nyasa, and went up the Shire river past scenes of devastation as Mariano's Chikunda slave-hunts caused famine, and they frequently had to clear the paddle wheels of corpses left floating downstream.

John Kirk, Charles Meller, and Richard Thornton, scientists appointed to work under Livingstone, contributed large collections of botanical, ecological, geological, and ethnographic material to scientific Institutions in the United Kingdom.

Livingstone believed that the source was farther south and assembled a team to find it consisting of freed slaves, Comoros Islanders, twelve Sepoys, and two servants from his previous expedition, Chuma and Susi.

[59][60] The cause behind this attack is stated to be retaliation for actions of Manilla, the head slave who had sacked villages of Mohombo people at the instigation of the Wagenya chieftain Kimburu.

[57] Following the end of the wet season, he travelled 240 miles (390 km) from Nyangwe back to Ujiji, an Arab settlement on the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika—violently ill most of the way—arriving on 23 October 1871.

However, the phrase appears in a New York Herald editorial dated 10 August 1872, and the Encyclopædia Britannica and the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography both quote it without questioning its veracity.

The words are famous because of their perceived humour, Livingstone being the only other white person for hundreds of miles, along with Stanley's clumsy attempt at appearing dignified in the bush of Africa by making a formal greeting one might expect to hear in the confines of an upper-class London club.

[67] As noted by his biographer Tim Jeal, Stanley struggled his whole life with a self-perceived weakness of being from a humble background, and manufactured events to make up for this supposed deficiency.

[68] Livingstone died on 1 May 1873 at the age of 60 in Chief Chitambo's village at Chipundu, southeast of Lake Bangweulu, in present-day Zambia, from malaria and internal bleeding due to dysentery.

[78] The expedition led by Chuma and Susi then carried the rest of his remains, together with his last journal and belongings, on a journey that took 63 days to the coastal town of Bagamoyo, a distance exceeding 1,000 miles (1,600 km).

The caravan encountered the expedition of English explorer Verney Lovett Cameron, who continued his march and reached Ujiji in February 1874, where he found and sent to England Livingstone's papers.

He also described: The strangest disease I have seen in this country seems really to be broken-heartedness, and it attacks free men who have been captured and made slaves... Twenty one were unchained, as now safe; however all ran away at once; but eight with many others still in chains, died in three days after the crossing.

[42] Livingstone was part of an evangelical and nonconformist movement in Britain which during the 19th century helped change the national mindset from the notion of a divine right to rule 'lesser races', to more modernly ethical ideas in foreign policy.

Congo Ghana Kenya Malawi Namibia South Africa Tanzania Uganda Zambia Zimbabwe New Zealand Scotland England Canada United States In 1971–1998 Livingstone's image was portrayed on £10 notes issued by the Clydesdale Bank.