David H. Malan

His father was English, working in the Indian Civil service as Paymaster General of Madras State, and his mother Isabel (née Allen)was American.

[1] At preparatory boarding school Malan particularly enjoyed learning Latin and Greek, but as a scholar at Winchester he became interested in chemistry which he then studied, winning a scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford.

During the war Malan was seconded to the Special Operations Executive (S.O.E), initially to develop devices for Resistance fighters, and later incendiary bombs for use in the Far East.

[3] In 1956, at the Tavistock Clinic, Balint asked him to join his Brief Psychotherapy research group investigating whether brief focal therapy was effective.

During his early years as a psychotherapist, he already advocated the accurate, reproducible clinical descriptions, as well as the prediction of desirable outcomes prior to the process of therapy or an "intention to treat", which are then followed by unbiased evaluation post-treatment.

[2] In 1967 Malan developed the Brief Psychotherapy workshop which all trainees were required to attend for one year and treat a patient under his supervision.

In 1974, Davanloo showed his tapes of Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy to Malan who was convinced by the evidence that the technique used was extremely effective.

They began a twelve-year collaboration, doing workshops and lectures together with Davanloo showing his tapes of therapy and Malan outlining the concepts and explaining the principles of the technique.

Butterworth-Heinnemann which outlines the principles of Dynamic Psychotherapy from the most elementary to the most profound, using true case histories to illustrate each concept.

[1][3] After his retirement, Malan continued to write and lecture extensively on Brief Psychotherapy and Intensive Short Term Dynamic Therapy (ISTDP), publishing his last book "Lives Transformed", in 2006, which he co-authored with Patricia Coughlin.

In 2005, Malan received a Career Achievement Award in recognition of his contribution to Psychotherapy from the International Experiential Dynamic Therapy Association, of which he was Emeritus President since its inception.

In 1956, after becoming a psychotherapist at the Tavistock Clinic, Malan was invited by Balint to join his Brief Psychotherapy research group investigating whether brief focal therapy was effective.

Patients were treated using a radical interpretive approach and the results were evaluated against specified criteria and, in general, they were extremely good.

Malan analysed the results in his Oxford DM thesis and subsequently developed the ideas in A Study of Brief Psychotherapy : Tavistock publications 1963.

An account of twenty-four therapies completed by trainees as part of the Brief Psychotherapy Workshop is summarised in ‘Psychodynamics, Training and Outcome’ by Malan and Osimo, pub.

It is based not only on the sessions but on the follow-up of a series of patients, and shows that good therapeutic results can be achieved by trainees under supervision.

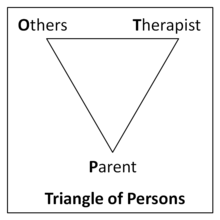

Malan always acknowledges that each Triangle was independently devised by Ezriel (1952) and Menninger (1958) respectively, but he showed how, when put together, the relation between them for the patient at any given moment in therapy, can form a reliable basis for many of the interventions that the therapist makes.

Malan maintains that the aim of every session is to ‘put the patient in touch with as much of their true feelings as they can bear and that the long-term outcome should demonstrate deep and lasting changes.’ The work does not have to be focal and limited to specific problems and should lead to therapeutic changes that are wide-ranging, deep-seated and permanent.

The essence of ISTDP is to enable the patient to reach and experience their hitherto buried, and often unconscious feelings, which have been governing their emotional responses leading to deep-seated neurotic patterns of behaviour that in many cases have crippled their lives.

He does this by challenging the defences that the patient has been using to avoid painful feelings of loss, grief, anger, hate and guilt about people who they loved and /or needed when children.

The videotapes showed undeniable evidence that patients could be treated in a relatively few sessions (40 or fewer) and fully recover from a range of longstanding emotional and psychosomatic illnesses.

Malan recognised that as long as the patient reaches and experiences the buried, often previously unconscious painful feelings, they no longer have the power to govern their emotional responses.

In order to introduce Intensive Short-term Dynamic Psychotherapy to the UK, Malan organised two Conferences in Oxford in 2006 and 2008, where video-tapes of therapies were shown.

He is convinced that psychodynamic processes can and should be scientifically studied, and he rigorously insists on long-term follow-ups to see how effective therapy really has been and what factors contributed to this.

He considers that questionnaires are useless, and proper follow-up interviews are necessary based on the initial criteria the therapist sets for the complete resolution of the presenting problems.

He published papers throughout his career evaluating outcome data which showed that the results of Brief Psychotherapy are as good as, or better than, those found in long-term therapy.