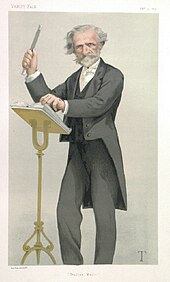

Giuseppe Verdi

By the time he was 12, he began lessons with Ferdinando Provesi, maestro di cappella at San Bartolomeo, director of the municipal music school and co-director of the local Società Filarmonica (Philharmonic Society).

Verdi was to claim that he gradually began to work on the music for Nabucco, the libretto of which had originally been rejected by the composer Otto Nicolai:[22] "This verse today, tomorrow that, here a note, there a whole phrase, and little by little the opera was written", he later recalled.

[10] At its revival in La Scala for the 1842 autumn season it was given an unprecedented (and later unequalled) total of 57 performances; within three years it had reached (among other venues) Vienna, Lisbon, Barcelona, Berlin, Paris and Hamburg; in 1848 it was heard in New York, in 1850 in Buenos Aires.

[36] The writer Andrew Porter notes that for the next ten years, Verdi's life "reads like a travel diary—a timetable of visits...to bring new operas to the stage or to supervise local premieres".

He relied on Piave again for I due Foscari, performed in Rome in November 1844, then on Solera once more for Giovanna d'Arco, at La Scala in February 1845, while in August that year he was able to work with Salvadore Cammarano on Alzira for the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples.

[44] Strepponi's voice declined and her engagements dried up in the 1845 to 1846 period, and she returned to live in Milan whilst retaining contact with Verdi as his "supporter, promoter, unofficial adviser, and occasional secretary" until she decided to move to Paris in October 1846.

Verdi agreed to adapt I Lombardi to a new French libretto; the result was Jérusalem, which contained significant changes to the music and structure of the work (including an extensive ballet scene) to meet Parisian expectations.

"[53] On hearing the news of the "Cinque Giornate", the "Five Days" of street fighting that took place between 18 and 22 March 1848 and temporarily drove the Austrians out of Milan, Verdi travelled there, arriving on 5 April.

[60] Verdi was committed to the publisher Giovanni Ricordi for an opera—which became Stiffelio—for Trieste in the Spring of 1850; and, subsequently, following negotiations with La Fenice, developed a libretto with Piave and wrote the music for Rigoletto (based on Victor Hugo's Le roi s'amuse) for Venice in March 1851.

[79] In the winter of 1851–52, Verdi decided to go to Paris with Strepponi, where he concluded an agreement with the Opéra to write what became Les vêpres siciliennes, his first original work in the style of grand opera.

In February 1852, the couple attended a performance of Alexander Dumas fils's play The Lady of the Camellias; Verdi immediately began to compose music for what would later become La traviata.

[80] After his visit to Rome for Il trovatore in January 1853, Verdi worked on completing La traviata, but with little hope of its success, due to his lack of confidence in any of the singers engaged for the season.

"[85] An 1858 letter by Strepponi to the publisher Léon Escudier describes the kind of lifestyle that increasingly appealed to the composer: "His love for the country has become a mania, madness, rage, and fury—anything you like that is exaggerated.

[89] Arriving in Sant'Agata in March 1859 Verdi and Strepponi found the nearby city of Piacenza occupied by about 6,000 Austrian troops who had made it their base, to combat the rise of Italian interest in unification in the Piedmont region.

His early commitment to the Risorgimento movement is difficult to estimate accurately; in the words of the music historian Philip Gossett "myths intensifying and exaggerating [such] sentiment began circulating" during the nineteenth century.

"[116] During the 1860s and 1870s, Verdi paid great attention to his estate around Busseto, purchasing additional land, dealing with unsatisfactory (in one case, embezzling) stewards, installing irrigation, and coping with variable harvests and economic slumps.

[120] Verdi spent much of 1872 and 1873 supervising the Italian productions of Aida at Milan, Parma and Naples, effectively acting as producer and demanding high standards and adequate rehearsal time.

[123] The spinto soprano Teresa Stolz, who had sung in La Scala productions from 1865 onwards, was the soloist in the first and many later performances of the Requiem; in February 1872, she had created Aida in its European premiere in Milan.

[130] Even more hectic scenes ensued when he went to Rome in May for the opera's premiere at the Teatro Costanzi; crowds of well-wishers at the railway station initially forced Verdi to take refuge in a tool-shed.

[138] Boito wrote to a friend, in words which recall the mysterious final scene of Don Carlos, "[Verdi] sleeps like a King of Spain in his Escurial, under a bronze slab that completely covers him.

[158] The musicologist Richard Taruskin suggested "the most striking effect in the early Verdi operas, and the one most obviously allied to the mood of the Risorgimento, was the big choral number sung—crudely or sublimely, according to the ear of the beholder—in unison.

The success of "Va, pensiero" in Nabucco (which Rossini approvingly denoted as "a grand aria sung by sopranos, contraltos, tenors and basses"), was replicated in the similar "O Signor, dal tetto natio" in I lombardi and in 1844 in the chorus "Si ridesti il Leon di Castiglia" in Ernani, the battle hymn of the conspirators seeking freedom.

[158] From this period onwards Verdi also develops his instinct for "tinta" (literally 'colour'), a term which he used for characterising elements of an individual opera score—Parker gives as an example "the rising 6th that begins so many lyric pieces in Ernani".

[163] The writer David Kimbell states that in Luisa Miller and Stiffelio (the earliest operas of this period) there appears to be a "growing freedom in the large scale structure...and an acute attention to fine detail".

The result was Les vêpres siciliennes, and the scenarios of Simon Boccanegra (1857), Un ballo in maschera (1859), La forza del destino (1862), Don Carlos (1867) and Aida (1871) all meet the same criteria.

Porter notes that Un ballo marks an almost complete synthesis of Verdi's style with the grand opera hallmarks, such that "huge spectacle is not mere decoration but essential to the drama...musical and theatrical lines remain taut [and] the characters still sing as warmly, passionately and personally as in Il trovatore.

[172] During the rehearsals for the Naples production of Aida Verdi amused himself by writing his only string quartet, a sprightly work which shows in its last movement that he had not lost the skill for fugue-writing that he had learned with Lavigna.

[175] Verdi's tone painting at the opening of the Requiem is vividly described by the Italian composer Ildebrando Pizzetti, writing in 1941: "in [the words] murmured by an invisible crowd over the slow swaying of a few simple chords, you straightaway sense the fear and sadness of a vast multitude before the mystery of death.

[208] But the same company's staging in 2002 of Un ballo in maschera as A Masked Ball, directed by Calixto Bieito, including "satanic sex rituals, homosexual rape, [and] a demonic dwarf", got a general critical thumbs down.

[210] In 2014, the pop singer Katy Perry appeared at the Grammy Award wearing a dress designed by Valentino, embroidered with the music of "Dell'invito trascorsa è già l'ora" from the start of La traviata.