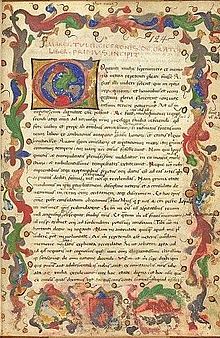

De Oratore

During this year, the author faces a difficult political situation: after his return from exile in Dyrrachium (modern Albania), his house was destroyed by the gangs of Clodius in a time when violence was common.

As a consequence, moral principles can be taken either by the examples of noble men of the past or by the great Greek philosophers, who provided ethical ways to be followed in their teaching and their works.

De Oratore is an exposition of issues, techniques, and divisions in rhetoric; it is also a parade of examples for several of them and it makes continuous references to philosophical concepts to be merged for a perfect result.

Despite De Oratore (On the Orator) being a discourse on rhetoric, Cicero has the original idea of inspiring himself to Plato's Dialogues, replacing the streets and squares of Athens with a nice garden of a country villa of a noble Roman aristocrat.

[5] The Greeks, after dividing the arts, paid more attention to the portion of oratory that is concerned with the law, courts, and debate, and therefore left these subjects for orators in Rome.

Indeed, all that the Greeks have written in their treaties of eloquence or taught by the masters thereof, but Cicero prefers to report the moral authority of these Roman orators.

Thereto also gathered Lucius Licinius Crassus, Quintus Mucius Scaevola, Marcus Antonius, Gaius Aurelius Cotta and Publius Sulpicius Rufus.

Lycurgus, Solon were certainly more qualified about laws, war, peace, allies, taxes, civil right than Hyperides or Demosthenes, greater in the art of speaking in public.

Similarly in Rome, the decemviri legibus scribundis were more expert in right than Servius Galba and Gaius Lelius, excellent Roman orators.

Nevertheless, Crassus maintains his opinion that "oratorem plenum atque perfectum esse eum, qui de omnibus rebus possit copiose varieque dicere".

No, they are gifts of nature, that is the ability to invent, richness in talking, strong lungs, certain voice tones, particular body physique as well as a pleasant looking face.

But the most striking thoughts and expressions come one after the other by the style; so the harmonic placing and disposing words is acquired by writing with oratory and not poetic rhythm (non poetico sed quodam oratorio numero et modo).

Indeed, only laws teach that everyone must, first of all, seek good reputation by the others (dignitas), virtue and right and honest labour are decked of honours (honoribus, praemiis, splendore).

Indeed, unlike the Greek orators, who need the assistance of some expert of right, called pragmatikoi, the Roman have so many persons who gained high reputation and prestige on giving their advice on legal questions.

The house of the expert of right (iuris consultus) is the oracle of the entire community: this is confirmed by Quintus Mucius, who, despite his fragile health and very old age, is consulted every day by a large number of citizens and by the most influent and important persons in Rome.

[31] Given that—Crassus continues—there is no need to further explain how much important is for the orator to know public right, which relates to government of the state and of the empire, historical documents and glorious facts of the past.

On the contrary, Antonius believes that an orator is a person, who is able to use graceful words to be listened to and proper arguments to generate persuasion in the ordinary court proceedings.

Marcus Cato, Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius, Gaius Lelius, all eloquent persons, used very different means to ornate their speeches and the dignity of the state.

In conclusion, if we want to put all the disciplines as a necessary knowledge for the orator, Antonius disagrees, and prefers simply to say that the oratory needs not to be nude and without ornate; on the contrary, it needs to be flavoured and moved by a graceful and changing variety.

Antonius finally acknowledges that an orator must be smart in discussing a court action and never appear as an inexperienced soldier nor a foreign person in an unknown territory.

After the judges condemned him, they asked him which punishment he would have believed suited for him and he replied to receive the highest honour and live for the rest of his life in the Pritaneus, at the state expenses.

In my opinion, says Antonius to Crassus, you deserved well your votes by your sense of humour and graceful speaking, with your jokes, or mocking many examples from laws, consults of the Senate and from everyday speeches.

If the young pupils wish to follow your invitation to read everything, to listen to everything and learn all liberal disciplines and reach a high cultural level, I will not stop them at all.

[47] Antonius agrees with Crassus for an orator, who is able to speak in such a way to persuade the audience, provided that he limits himself to the daily life and to the court, renouncing to other studies, although noble and honourable.

He shares with Lucius Crassus, Quintus Catulus, Gaius Julius Caesar Strabo, and Sulpicius his opinion on oratory as an art, eloquence, the orator's subject matter, invention, arrangement, and memory.

Antonius asserts that oratory is "a subject that relies on falsehood, that seldom reaches the level of real knowledge, that is out to take advantage of people's opinions and often their delusions" (Cicero, 132).

Within laudatory speeches it is necessary include the presence of “descent, money, relatives, friends, power, health, beauty, strength, intelligence, and everything else that is either a matter of the body or external" (Cicero, 136).

He then lists the three means of persuasion that are used in the art of oratory: "proving that our contentions are true, winning over our audience, and inducing their minds to feel any emotion the case may demand" (153).

Cicero adds that, in his opinion, the immortal gods gave Crassus his death as a gift, to preserve him from seeing the calamities that would befall the State a short time later.

Indeed, he has not seen Italy burning by the social war (91-87 BC), neither the people's hate against the Senate, the escape and return of Gaius Marius, the following revenges, killings and violence.