Dean Mahomed

Dean Mahomed (1759–1851) was a British Indian traveller, soldier, surgeon, entrepreneur, and one of the most notable early non-European immigrants to the Western World.

[3][4] "so long as the Sepoys maintain their formations, which they call 'lines', they are like an immovable volcano spewing artillery and rifle fire like unrelenting hail on the enemy, and they are seldom defeated."

Born c. May 1759 in the city of Patna, then part of the Bengal Subah of the Mughal Empire and today the capital of the Indian state of Bihar.

[5] Dean Mahomed described himself as a "native of Patna"[6] belonging to a Shia Muslim family that claimed Arab and Afshar Turk origin.

I was educated to the profession of, and served in the Company's Service, as a Surgeon, which capacity I afterwards relinquished, and acted in a military character, exclusively for nearly fifteen years.

[13] There he studied to improve his English language skills at a local school, and fell in love with Jane Daly, a "pretty Irish girl of respectable parentage".

His most famous grandson, Frederick Henry Horatio Akbar Mahomed (c. 1849–1884), became an internationally known physician[15] and worked at Guy's Hospital in London.

[31] During the war, Frederick and James' children changed their surnames from Mahomed to Deane and Wyatt, respectively, in order to avoid xenophobic attention at a time when racial prejudice was rife and mixed marriages were disapproved of.

A series of military conflicts are described along with descriptions of some major cities, including Kolkata (Calcutta) and Varanasi (Benares).

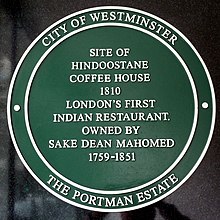

[38] The restaurant offered, among other items, hookah "with real chilm tobacco, and Indian dishes, ... allowed by the greatest epicures to be unequalled to any curries ever made in England.

[25] Before opening his restaurant, Mahomed had worked in London for nabob Basil Cochrane, who had installed a steam bath for public use in his house in Portman Square and promoted its medical benefits.

[41][24] In this work, Mahomed speaks of the initial resistance to the idea of shampooing among the English he encountered in his new country: "It is not in the power of any individual to give unqualified satisfaction, or to attempt to establish a new opinion without the risk of incurring the ridicule, as well as censure, of some portion of mankind.

So it was with me: in the face of indisputable evidence, I had to struggle with doubts and objections raised and circulated against my Bath, which, but for the repeated and numerous cures effected by it, would long since have shared the common fate of most innovations in science.

[43] After his death in 1851, Sake Dean Mahomed, once so renowned in Ireland and Brighton's social scenes, began to lose prominence as a public figure and until the scholarly interventions of the last fifty years was largely forgotten by history.

Michael H. Fisher has written a book on Mahomet entitled The First Indian Author in English: Dean Mahomed in India, Ireland, and England (Oxford University Press, Delhi, 1996).

Additionally, Rozina Visram's Ayahs, Lascars and Princes: The Story of Indians in Britain 1700–1947 (1998) was highly influential in drawing public attention to Mahomed's life and work.