Dear Bill

The letters were split equally between reactionary grumblings about the state of the country and vituperative comments on contemporary politics, with regular passing references to the goings-on of a fictional collection of acquaintances and the consumption of a quite remarkable quantity of "electric soup".

It allowed the writers wide rein to comment on the personal peculiarities of senior politicians without seeming overly absurd, and was presented in a context that was – whilst clearly fictional – quite plausible.

The assumed characteristics of the subject – a conservative reactionary, a "buffer's buffer" surveying the world through the bottom of a glass and not liking it one inch – gave ample opportunity for a rich and identifiable style; the image of Denis portrayed in the letters – a gin-soaked half-witted layabout, whose sole activity was to try to escape the wrath of "the Boss" – was a popular one, and Denis Thatcher remained in the public imagination as a less gaffe-prone version of the Duke of Edinburgh long after both the Thatcher government and the series itself had ended.

The poet Philip Larkin described the letters as consolidating "an imaginative reality that is more convincing than the morning papers" in an Observer review, and John Wells once argued that he had done more than every Downing Street publicist to endear the Thatchers to the British public.

[citation needed] Bill Deedes, along with the Thatchers' daughter Carol, argued that Denis himself played up to this image – by encouraging the portrayal of himself as a harmlessly incompetent buffoon, he could deflect any claims that he was manipulating government from "behind the throne".

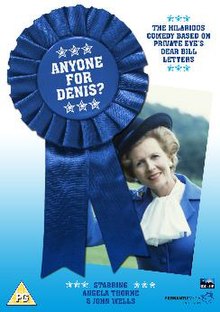

cover drawing by George Adamson