Amanita phalloides

Originating in Europe[1] but later introduced to other parts of the world since the late twentieth century,[2][3][4][5] A. phalloides forms ectomycorrhizas with various broadleaved trees.

The large fruiting bodies (mushrooms) appear in summer and autumn; the caps are generally greenish in colour with a white stipe and gills.

Amatoxins, the class of toxins found in these mushrooms, are thermostable: they resist changes due to heat, so their toxic effects are not reduced by cooking.

The term "destroying angel" has been applied to A. phalloides at times, but "death cap" is by far the most common vernacular name used in English.

[34] Young specimens first emerge from the ground resembling a white egg covered by a universal veil, which then breaks, leaving the volva as a remnant.

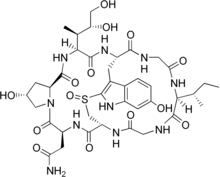

[35][36] The species is now known to contain two main groups of toxins, both multicyclic (ring-shaped) peptides, spread throughout the mushroom and d cell–destroying activity in vitro.

Amatoxins consist of at least eight compounds with a similar structure, that of eight amino-acid rings; they were isolated in 1941 by Heinrich O. Wieland and Rudolf Hallermayer of the University of Munich.

[44] A. phalloides is similar to the edible paddy straw mushroom (Volvariella volvacea)[45] and A. princeps, commonly known as "white Caesar".

[50] In Europe, other similarly green-capped species collected by mushroom hunters include various green-hued brittlegills of the genus Russula and the formerly popular Tricholoma equestre, now regarded as hazardous owing to a series of restaurant poisonings in France.

[51] Other similar species include A. subjunquillea in eastern Asia and A. arocheae, which ranges from Andean Colombia north at least as far as central Mexico, both of which are also poisonous.

[56] In 1918, samples from the eastern United States were identified as being a distinct though similar species, A. brunnescens, by George Francis Atkinson of Cornell University.

[2] By the 1970s, it had become clear that A. phalloides does occur in the United States, apparently having been introduced from Europe alongside chestnuts, with populations on the West and East Coasts.

[2][57] A 2006 historical review concluded the East Coast populations were inadvertently introduced, likely on the roots of other purposely imported plants such as chestnuts.

[59] Observations of various collections of A. phalloides, from conifers rather than native forests, have led to the hypothesis that the species was introduced to North America multiple times.

[4] Pine plantations are associated with the fungus in Tanzania[67] and South Africa, found under oaks and poplars in Chile,[68][69] as well as Uruguay.

There is, however, evidence of A. phalloides associating with hemlock and with genera of the Myrtaceae: Eucalyptus in Tanzania[67] and Algeria,[53] and Leptospermum and Kunzea in New Zealand,[25][73] suggesting that the species may have invasive potential.

[74] As the common name suggests, the fungus is highly toxic, and is responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings worldwide.

[11][75] Its biochemistry has been researched intensively for decades,[2] and 30 grams (1.1 ounces), or half a cap, of this mushroom is estimated to be enough to kill a human.

[78] Some authorities strongly advise against putting suspected death caps in the same basket with fungi collected for the table and to avoid even touching them.

Recent cases highlight the issue of the similarity of A. phalloides to the edible paddy straw mushroom (Volvariella volvacea), with East- and Southeast-Asian immigrants in Australia and the West Coast of the U.S. falling victim.

[45] Many North American incidents of death cap poisoning have occurred among Laotian and Hmong immigrants, since it is easily confused with A. princeps ("white Caesar"), a popular mushroom in their native countries.

Initially, symptoms are gastrointestinal in nature and include colicky abdominal pain, with watery diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting, which may lead to dehydration if left untreated, and, in severe cases, hypotension, tachycardia, hypoglycemia, and acid–base disturbances.

The four main categories of therapy for poisoning are preliminary medical care, supportive measures, specific treatments, and liver transplantation.

[91][92] Supportive measures are directed towards treating the dehydration which results from fluid loss during the gastrointestinal phase of intoxication and correction of metabolic acidosis, hypoglycemia, electrolyte imbalances, and impaired coagulation.

High-dose continuous intravenous penicillin G has been reported to be of benefit, though the exact mechanism is unknown,[89] and trials with cephalosporins show promise.

[93][94] Some evidence indicates intravenous silibinin, an extract from the blessed milk thistle (Silybum marianum), may be beneficial in reducing the effects of death cap poisoning.

[91] Repeated doses of activated carbon may be helpful by absorbing any toxins returned to the gastrointestinal tract following enterohepatic circulation.

[104] Other methods of enhancing the elimination of the toxins have been trialed; techniques such as hemodialysis,[105] hemoperfusion,[106] plasmapheresis,[107] and peritoneal dialysis[108] have occasionally yielded success, but overall do not appear to improve outcome.

[91] That being the case, the criteria have been reassessed, such as onset of symptoms, prothrombin time (PT), serum bilirubin, and presence of encephalopathy, for determining at what point a transplant becomes necessary for survival.

[110][111][112] Evidence suggests, although survival rates have improved with modern medical treatment, in patients with moderate to severe poisoning, up to half of those who did recover suffered permanent liver damage.