Death of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

25 October],[a 1] nine days after the premiere of his Sixth Symphony, the Pathétique, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky died in Saint Petersburg, at the age of 53.

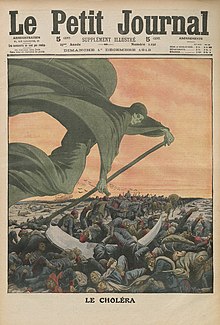

[1] The timeline between when Tchaikovsky drank unboiled water, how he obtained this at a reputable restaurant during a cholera epidemic with strict health regulations, and the emergence of symptoms was brought into question.

Since 1979, one variation of the theory has gained some ground—a sentence of suicide imposed in a "court of honor" by Tchaikovsky's fellow alumni of the Imperial School of Jurisprudence, as a censure of the composer's homosexuality.

Afterwards, he went with his brother Modest, his nephew Vladimir Davydov, the composer Alexander Glazunov, and other friends to a restaurant named Leiner's, located in Kotomin House at Nevsky Prospekt, Saint Petersburg.

[2] The next morning, at Modest's apartment, Pyotr was not in the sitting room drinking tea as usual, but in bed complaining of diarrhea and an upset stomach.

Among the guests, composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov was seemingly bewildered by what he saw:[5] "How strange that, although death had resulted from cholera, still admission to the Mass for the dead was free to all!

I remember how [Alexander] Verzhbilovich [a cellist and professor at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory], totally drunk ... kept kissing the deceased man's head and face.

Diaghilev, who would become known as the founder and impresario of the Ballets Russes, was at that time a university student in St. Petersburg and had met and occasionally conversed with the composer,[7] to whom he was distantly related by marriage.

)[11] According to Poznansky, with the added precaution of constant disinfectant to the lips and nostrils of the body, even the drunken cellist kissing the face of the deceased had little cause for worry.

[10] Alexander III volunteered to pay the costs of the composer's funeral himself and instructed the Directorate of the Imperial Theatres to organise the event.

[17] Holden adds that, according to contemporary Russian medical records, the specific epidemic which claimed Tchaikovsky's life began on 14 May 1892 and ended on 11 February 1896.

[17] Even with these numbers, the attribution of Tchaikovsky's death to cholera appeared to degrade his reputation among the upper classes and struck many as inconceivable.

[24] A writer for Russian Life noted, "[E]veryone is astounded by the uncommon occurrence of the lightning-fast infection with Asiatic cholera of a man so very temperate, modest, and austere in his daily habits.

If the one-to-three-day interval is taken as 24 to 72 hours, the latest the composer could have been infected would have been Wednesday morning, earlier than either the dinner at Leiner's that evening or lunch at Modest's the following afternoon.

"We find it extremely strange that a good restaurant could have served unboiled water during an epidemic", wrote a reporter for the newspaper Son of the Fatherland.

[35] Another factor Pozansky mentions is that Tchaikovsky, already in gastric distress Thursday morning, drank a glass of the alkaline mineral water "Hunyadi János" in an attempt to ease his stomach.

[33] Referencing cholera specialist Valentin Pokovsky, Holden mentions another way Tchaikovsky could have contracted cholera—the "fecal-oral route", from less-than-hygienic sexual practices with male prostitutes in St.

[36] While Holden admits no further evidence supports this theory, he asserts that had it actually been the case, Tchaikovsky and Modest would have both gone to great pains to conceal the truth.

The key witness for Orlova's account was Alexander Voitrov, a pupil at the School of Jurisprudence before World War I who had reportedly amassed much about the history and people of his alma mater.

Jacobi's widow, Elizaveta Karlovna, reportedly told Voitrov in 1913 that a Duke Stenbok-Fermor was disturbed by the attention which Tchaikovsky was paying to his young nephew.

Brown suggests that perhaps it is significant that Modest records his brother's last days from that evening, when Tchaikovsky attended Anton Rubinstein's opera Die Maccabäer.

This story was told by Swiss musicologist Robert-Aloys Mooser, who supposedly learned it from two others—Riccardo Drigo, composer and kapellmeister to the St. Petersburg Imperial Theatres, and Glazunov.

Mooser considered Glazunov a reliable witness, stressing his "upright moral character, veneration for the composer and friendship with Tchaikovsky.

It was exactly this circle of intimates, however, that Drigo accused of concealing the "truth", [Poznansky's quotation marks for emphasis] demanding false testimonies from authorities, physicians and priests.

He supposedly poured his misery onto this one last great work as a conscious prelude to suicide, then drank unboiled water in the hope of contracting cholera.

Rumor attached to the famous die hard ... As for illness, problems of evidence offer little hope of satisfactory resolution: the state of diagnosis; the confusion of witnesses; disregard of long-term effects of smoking and alcohol.

We may never find out...."[49] In the early 1980s, the Canadian composer Claude Vivier had begun working on an opera entitled Tchaïkovski, un réquiem Russe (lit.

Vivier announced the project to UNESCO music organizations and had begun writing a libretto, but he was murdered in a 1983 homophobic hate crime before the opera could be completed.

"[9] Regardless of its initial reception, two weeks after Tchaikovsky's death, on 18 November 1893, the composer's longtime friend, conductor Eduard Nápravník, led the second performance of the Sixth Symphony at a memorial concert in St. Petersburg.

The musical clues include one in the development section of the first movement, where the rapidly progressing evolution of the transformed first theme suddenly "shifts into neutral" in the strings, and a rather quiet, harmonized chorale emerges in the trombones.