Death of Starr Faithfull

[3] An autopsy found that she had died by drowning, but also bore many bruises, apparently caused by beating or rough handling, and a large dose of a sedative in her system.

[2] A grand jury convened to hear evidence returned an open verdict, and the case was closed with no definitive conclusion as to whether Faithfull's death was a homicide, suicide, or an accident.

[3][4] Faithfull's death made national and international news due to its many sensational aspects, including her youth, beauty, promiscuity, and flapper lifestyle, as well as the allegations about Peters.

[8] Starr's mother Helen came from a wealthy, socially established family, but her father Frank lost his fortune before she was married, leaving her relatively poor.

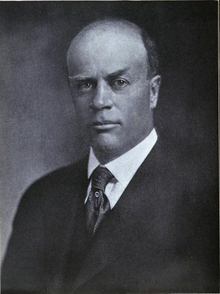

[9][10] Her cousin Martha had married Andrew James Peters,[11] a career politician who served as member of both the Massachusetts House and Senate; a U.S. congressman; an assistant secretary of the Treasury under U.S. President Woodrow Wilson; and mayor of Boston from 1918 to 1922.

[12] As mayor, Peters was known for his failure to avert the 1919 Boston Police Strike, which helped raise the national profile of Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge.

The Peters family were among the relatives who helped support the Wymans by giving Helen monetary gifts and paying for her daughters' private school educations.

Stanley, a widower who was previously married to the governess of Leverett Saltonstall,[2] was a self-employed inventor and entrepreneur who failed at numerous business ventures and earned little or no money.

The Faithfulls initially settled in West Orange, New Jersey, but lost their heavily mortgaged house to foreclosure and moved to an apartment at 12 St. Luke's Place in New York City.

[2] Stanley engaged an attorney and, in 1927, negotiated a written settlement agreement with Peters, whereby he paid the Faithfulls $20,000—supposedly to cover Starr's medical care and rehabilitation[19]—in return for keeping the abuse secret.

[27] Russel Crouse, who wrote an early true crime account of the case, stated that the investigators "did come upon some evidence that someone other than the Faithfull family had heard the story and had attempted to make use of it in Boston.

"[28] Investigators learned after Faithfull's death that her mother and stepfather, acting on doctors' advice, had paid artist Edwin Megargee to be her "sex tutor" and teach her how to have normal sexual relations after her traumatic experiences with Peters.

[29] Money received from Peters was also used to send her away on cruises to the Mediterranean, the West Indies and five or six times to the United Kingdom, where she stayed for extended periods in London.

[30] When not going on cruises, Faithfull regularly attended the "bon voyage" parties held on ocean liners in port before their departures from New York, often socializing with the ships' officers.

[21][32] After Carr made Faithfull leave his sitting room because the ship was departing, she remained on deck when Franconia left the dock, despite having no ticket (which at that point she could not afford).

Investigators discovered that after she left the house that day, she made multiple trips to ocean liners docked in Manhattan, where she visited ship's officers.

[42] Faithfull's family reported seeing her for the last time leaving their apartment on St. Luke's Place at 9:30am on the morning of Friday, June 5, wearing an expensive silk dress, hat, gloves, shoes and stockings, and carrying a purse and coat.

Roberts said that shortly after 10:00pm, he gave Faithfull a dollar for cab fare and put her into a taxi near Pier 56, supposedly to drive her to another ocean liner, the Île de France, on which she planned to attend a party.

[49] Police informants later told investigators that on Saturday, June 6, a woman fitting Faithfull's description had been seen with a male companion at Tappe's Hotel in Island Park, New York, near Long Beach.

Neither her dress nor her manicured nails were damaged, although her body showed numerous bruises that the medical examiner stated had been inflicted before death, apparently by another person.

The investigation into Faithfull's death was led by Nassau County Police Inspector Harold King, Nassau County District Attorney Elvin Edwards, and Assistant DA Martin Littleton Jr. After identifying his stepdaughter's body, Stanley told King and Littleton that he believed Peters had ordered her murder in order to prevent her from revealing her past sexual abuse.

[55][56] The man named "Brucie", mentioned by taxi driver Edelman, was at first thought to be the actor "Bruce Winston", whom Faithfull had said she met at Cerf's party.

[32][38] In the first letter, dated May 30, Faithfull wrote, I am going (definitely now – I've been thinking of it for a long time) to end my worthless, disorderly bore of an existence – before I ruin any one else's life as well.

[38] In the third letter, written the day before she disappeared, Faithfull expressed in detail her intent and plans to die by suicide because she could not cope with her unrequited love for Carr.

[25] After the evidence of Faithfull's possible suicide came to light in late June 1931, the grand jury proceedings were closed, with no indictments issued, and the case began to fade from the headlines.

Stanley, anxious to keep the press interested in the story, continued to state that his stepdaughter was murdered by hired killers acting on behalf of a high-profile person.

[71] Nash and reporter Morris Markey, who covered the case in 1931 for The New Yorker, both theorized that based on the evidence and Faithfull's past behavior, including the hotel incident that resulted in her being taken to Bellevue Hospital, she had likely been killed on the beach by an unknown man after a sexual encounter had gone wrong.

Once there, she removed most of her clothing, but then teased or refused sex until the man became enraged, beat her, and drowned her in the shallow water and sand near the shoreline, possibly after sexually assaulting her.

[2][81] O'Hara was not involved in writing the film adaptation, which bore little resemblance to his novel and ended with Gloria's death in an automobile accident, rather than a suicide or homicide by drowning.

[100] Reviewer Paul Nigol of the University of Calgary called The Passing of Starr Faithfull "the most complete account" of the case because Goodman was the only author to have been granted full access to the police dossier.