Decompression (diving)

During ascent, the ambient pressure is reduced, and at some stage the inert gases dissolved in any given tissue will be at a higher concentration than the equilibrium state and start to diffuse out again.

If the pressure reduction is sufficient, excess gas may form bubbles, which may lead to decompression sickness, a possibly debilitating or life-threatening condition.

A mismanaged decompression usually results from reducing the ambient pressure too quickly for the amount of gas in solution to be eliminated safely.

If the decompression is effective, the asymptomatic venous microbubbles present after most dives are eliminated from the diver's body in the alveolar capillary beds of the lungs.

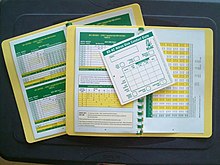

Tables and algorithms for predicting the outcome of decompression schedules for specified hyperbaric exposures have been proposed, tested and used, and in many cases, superseded.

Although constantly refined and generally considered acceptably reliable, the actual outcome for any individual diver remains slightly unpredictable.

It can take up to 24 hours for the body to return to its normal atmospheric levels of inert gas saturation after a dive.

The development of schedules that are both safe and efficient has been complicated by the large number of variables and uncertainties, including personal variation in response under varying environmental conditions and workload.

[1][2] In all cases, the symptoms of decompression sickness occur during or within a relatively short period of hours, or occasionally days, after a significant reduction of ambient pressure.

Under equilibrium conditions, the total concentration of dissolved gases is less than the ambient pressure—as oxygen is metabolised in the tissues, and the carbon dioxide produced is much more soluble.

[8][9] Since bubbles can form in or migrate to any part of the body, DCS can produce many symptoms, and its effects may vary from joint pain and rashes to paralysis and death.

[10] Actual rates of diffusion and perfusion, and solubility of gases in specific physiological tissues are not generally known, and vary considerably.

[15] What is commonly known as no-decompression diving, or more accurately no-stop decompression, relies on limiting ascent rate for avoidance of excessive bubble formation.

[26][27] The precise mechanisms of bubble formation[28] and the damage they cause has been the subject of medical research for a considerable time and several hypotheses have been advanced and tested.

Tables and algorithms for predicting the outcome of decompression schedules for specified hyperbaric exposures have been proposed, tested, and used, and usually found to be of some use but not entirely reliable.

[34] In 1908 John Scott Haldane prepared the first recognized decompression table for the British Admiralty, based on extensive experiments on goats using an end point of symptomatic DCS.

[36] During the 1930s, Hawkins, Schilling and Hansen conducted extensive experimental dives to determine allowable supersaturation ratios for different tissue compartments for Haldanean model,[37] Albert R. Behnke and others experimented with oxygen for re-compression therapy,[29] and the US Navy 1937 tables were published.

This indicates the importance of minimizing bubble phase for efficient gas elimination,[39][40] Groupe d'Etudes et Recherches Sous-marines published the French Navy MN65 decompression tables, and Goodman and Workman introduced re-compression tables using oxygen to accelerate elimination of inert gas.

[41][42] The Royal Naval Physiological Laboratory published tables based on Hempleman's tissue slab diffusion model in 1972,[43] isobaric counterdiffusion in subjects who breathed one inert gas mixture while being surrounded by another was first described by Graves, Idicula, Lambertsen, and Quinn in 1973,[44][45] and the French government published the MT74 Tables du Ministère du Travail in 1974.

From 1976, decompression sickness testing sensitivity was improved by ultrasonic methods that can detect mobile venous bubbles before symptoms of DCS become apparent.

[46] Paul K Weathersby, Louis D Homer and Edward T Flynn introduced survival analysis into the study of decompression sickness in 1982.

[17] Bühlmann recognised the problems associated with altitude diving, and proposed a method that calculated maximum nitrogen loading in the tissues at a particular ambient pressure by modifying Haldane's allowable supersaturation ratios to increase linearly with depth.

[48] In 1984 DCIEM (Defence and Civil Institution of Environmental Medicine, Canada) released No-Decompression and Decompression Tables based on the Kidd/Stubbs serial compartment model and extensive ultrasonic testing,[49] and Edward D. Thalmann published the USN E-L algorithm and tables for constant PO2 Nitrox closed circuit rebreather applications, and extended use of the E-L model for constant PO2 Heliox CCR in 1985.