Deconstruction

The concept of deconstruction was introduced by the philosopher Jacques Derrida, who described it as a turn away from Platonism's ideas of "true" forms and essences which are valued above appearances.

[14]: 25 Derrida published a number of other works directly relevant to the concept of deconstruction, such as Différance, Speech and Phenomena, and Writing and Difference.

[19]: 41 [contradictory] Derrida further argues that it is not enough to expose and deconstruct the way oppositions work and then stop there in a nihilistic or cynical position, "thereby preventing any means of intervening in the field effectively".

Derrida called these undecidables—that is, unities of simulacrum—"false" verbal properties (nominal or semantic) that can no longer be included within philosophical (binary) opposition.

Instead, they inhabit philosophical oppositions[further explanation needed]—resisting and organizing them—without ever constituting a third term or leaving room for a solution in the form of a Hegelian dialectic (e.g., différance, archi-writing, pharmakon, supplement, hymen, gram, spacing).

Derrida's views on deconstruction stood in opposition to the theories of structuralists such as psychoanalytic theorist Jacques Lacan, and anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss.

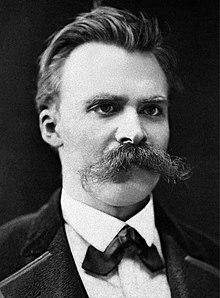

Derrida's motivation for developing deconstructive criticism, suggesting the fluidity of language over static forms, was largely inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophy, beginning with his interpretation of Trophonius.

Mere proposals of heightened reasoning, logic, philosophizing and science are no longer solely sufficient as the royal roads to truth.

[21] Derrida approaches all texts as constructed around elemental oppositions which all discourse has to articulate if it intends to make any sense whatsoever.

[21][page needed] Like Nietzsche, Derrida suspects Plato of dissimulation in the service of a political project, namely the education, through critical reflections, of a class of citizens more strategically positioned to influence the polis.

Michel Foucault, for instance, famously misattributed to Derrida the very different phrase Il n'y a rien en dehors du texte for this purpose.

This means that there is an assumed bias in certain binary oppositions where one side is placed in a position over another, such as good over bad, speech over the written word, male over female.

This argument is largely based on the earlier work of Heidegger, who, in Being and Time, claimed that the theoretical attitude of pure presence is parasitical upon a more originary involvement with the world in concepts such as ready-to-hand and being-with.

[29]: 3 Commentator Richard Beardsworth explains that: Derrida is careful to avoid this term [method] because it carries connotations of a procedural form of judgement.

A thinker with a method has already decided how to proceed, is unable to give him or herself up to the matter of thought in hand, is a functionary of the criteria which structure his or her conceptual gestures.

Particularly problematic are the attempts to give neat introductions to deconstruction by people trained in literary criticism who sometimes have little or no expertise in the relevant areas of philosophy in which Derrida is working.

[citation needed] Cambridge Dictionary states that deconstruction is "the act of breaking something down into its separate parts in order to understand its meaning, especially when this is different from how it was previously understood".

By demonstrating the aporias and ellipses of thought, Derrida hoped to show the infinitely subtle ways that this originary complexity, which by definition cannot ever be completely known, works its structuring and destructuring effects.

[42] Deconstruction denotes the pursuing of the meaning of a text to the point of exposing the supposed contradictions and internal oppositions upon which it is founded—supposedly showing that those foundations are irreducibly complex, unstable, or impossible.

[45] Derrida initially resisted granting to his approach the overarching name deconstruction, on the grounds that it was a precise technical term that could not be used to characterize his work generally.

Derrida's essay was one of the earliest to propose some theoretical limitations to structuralism, and to attempt to theorize on terms that were clearly no longer structuralist.

[48] Between the late 1960s and the early 1980s, many thinkers were influenced by deconstruction, including Paul de Man, Geoffrey Hartman, and J. Hillis Miller.

Self and other, private and public, subjective and objective, freedom and control are examples of such pairs demonstrating the influence of opposing concepts on the development of legal doctrines throughout history.

Derrida's thinking has inspired Slavoj Zizek, Richard Rorty, Ernesto Laclau, Judith Butler and many more contemporary theorists who have developed a deconstructive approach to politics.

Because deconstruction examines the internal logic of any given text or discourse it has helped many authors to analyse the contradictions inherent in all schools of thought; and, as such, it has proved revolutionary in political analysis, particularly ideology critiques.

Author David Hayward said he "co-opted the term" deconstruction because he was reading the work of Derrida at the time his religious beliefs came into question.

[58][59] Derrida was involved in a number of high-profile disagreements with prominent philosophers, including Michel Foucault, John Searle, Willard Van Orman Quine, Peter Kreeft, and Jürgen Habermas.

Later in 1988, Derrida tried to review his position and his critiques of Austin and Searle, reiterating that he found the constant appeal to "normality" in the analytical tradition to be problematic.

The American philosopher Walter A. Davis, in Inwardness and Existence: Subjectivity in/and Hegel, Heidegger, Marx and Freud, argues that both deconstruction and structuralism are prematurely arrested moments of a dialectical movement that issues from Hegelian "unhappy consciousness".

[74] He subsequently presented his views in the article "How to Deconstruct Almost Anything", where he stated, "Contrary to the report given in the 'Hype List' column of issue #1 of Wired ('Po-Mo Gets Tek-No', page 87), we did not shout down the postmodernists.