Decriminalization of homosexuality in Ecuador

The decriminalization of homosexuality in Ecuador took place on 25 November 1997, when the Constitutional Tribunal issued a landmark decision in Case 111-97-TC declaring the first clause of Article 516 of the Penal Code – which criminalized same-sex sexual relations as a crime with a penalty of four to eight years of imprisonment – unconstitutional.

The ruling put an end to more than one hundred years of criminalization of homosexuality and was the result of a claim filed by different LGBTQ groups as a response to the police abuses usually experienced by sexually diverse individuals in Ecuador.

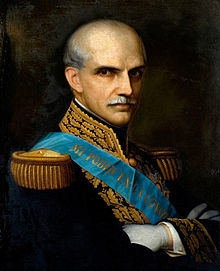

However, this caused an increase in police repression,[3] particularly during León Febres-Cordero Ribadeneyra's presidency (1984–1988), when human rights violations were committed against different groups of people, including LGBT populations.

[7][8] What happened at Bar Abanicos became the catalyst that prompted – for the first time in the history of the country – the organization of a front formed by different groups of people from the LGBT community to seek the decriminalization of homosexuality.

[11] On 24 September 1997, the petition was filed along with 1400 supporting signatures,[12][13] of which the allegations were based on three main arguments:[14] On 25 November 1997, the Constitutional Court unanimously decriminalized homosexuality in Ecuador.

If the assault has been committed by the parents, the guilty party will be deprived, in addition, of the rights and prerogatives that the Civil Code grants over the person and property of the offspring.In 1933, the Ecuadorian psychoanalyst and writer Humberto Salvador published the book Esquema sexual, highly successful in Latin America, in which he took a position against the criminalization of homosexuality in Ecuador based on clinical and scientific points of view.

[4] In May 1985, Febres-Cordero created the Escuadrones volantes,[Note 1] a group of special forces police that committed systematic violations of human rights and acts of torture with government consent.

[25] Based on the testimony of activists of the time, the Febres-Cordero government instilled panic in the LGBT community, who would run as soon as they saw a police patrol or a flying squad member approaching.

Activist Jorge Medranda testified that transgender women and gay men with characteristics considered "effeminate" received the worst treatment during raids in bars and discotheques and were often beaten and pulled by the hair to be arrested.

[28] During the 1990s, the Fundación Ecuatoriana de Acción y Educación para la Promoción de la Salud (FEDAEPS)[Note 4] – which was officially dedicated to preventing the spread of HIV but also carried out activities on behalf of LGBT rights – strengthened its links with foreign organizations, including the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA), through discussions where they shared strategies for activism and started submitting complaints about abuses against people from the LGBT community.

[5] On 7 November 1994,[29] the organizations used the presence in the country of a delegation from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) to submit a report compiling data on cases of police abuse.

[5] The foundation's connections with ILGA were of particular help for this purpose, since during its 1995 world conference – held 18–25 June in Rio de Janeiro – the association called for campaigns to decriminalize homosexuality in Ecuador, Chile and Nicaragua.

Simultaneously, members of FEDAEPS initiated a lobbying process in Congress to pursue the abolition of the criminalization of homosexuality, for which they held meetings with congressmen such as José Cordero, of the Popular Democracy party.

Terreros decided to file a complaint with the Human Rights Commission of Azuay and personally approached the city's media to demand a less discriminatory treatment and to recount the abuses suffered during the detentions, which led to a change in coverage to focus on the denunciation against the police,[37] particularly considering that there were members of upper class families from Cuenca among the detainees.

FEDAEPS and the Fundación Regional de Asesoría en Derechos Humanos[Note 9] (INREDH) have been working to promote the idea of change through the National Congress.

[47] This first lobbying process won the support of some legislators, including Rosendo Rojas, deputy of the province of Azuay for the Pachakutik Plurinational Unity Movement, who was very much in favor of decriminalization.

[49] This led APDH to propose a second route, consisting of making the change by means of an unconstitutionality claim against Article 516 of the Penal Code, a strategy favored by Coccinelle Association.

To file the claim, they were advised by Ernesto López, who had been president of the Constitutional Tribunal until February of that year and who guided them through the process – which required the collection of 1,000 supporting signatures.

[10] Coccinelle Association became prominent during the collection process and on 27 August of the same year, organized a transgender women,[50][51] gay men and human rights defenders march that went through the streets of Quito and ended at Plaza Grande, where they joined groups demanding justice for missing persons and managed to get 300 signatures for decriminalization.

Other strategies used during the campaign included the use of graffiti to promote messages such as "Despenalización ahora"[Note 10] and even an invitation to interim president Fabián Alarcón to discuss the issue.

"Another prominent figure who supported decriminalization was the then governor of Azuay, Felipe Vega de la Cuadra,[56][58] as well as the chef and television presenter Gino Molinari, who was among those able to collect the largest number of signatures in Guayaquil.

[13] The documents were presented by Cristian Polo Loayza, Jimmy Wider Coronado Tello, Silvia Haro Proaño, José Urriola Pérez and Gonzalo Abarca, who were joined by Ernesto López, former president of the Court.

Meanwhile, the Ecuadorian Episcopal Conference was in favor of withdrawing the first clause of the article for "an application of the principles of democratic tolerance and respect for the privacy of individuals", although in the same letter it rejected the existence of a right to sexuality.

Therefore, the criminalization of homosexuality is unconstitutional and against human rights.In response to international pressure in favor of decriminalization, the United Nations (UN) sent two representatives to meet with the Constitutional Court judges personally and urge them to accept the petition.

Then they contacted Anglican Bishop Walter Crespo, who agreed to hold a religious service in the Plaza de la Independencia to promote the message that "Homosexuals are also children of God.

[15] The Court decided not to declare the entire article unconstitutional and allowed the second and third paragraphs – regarding homosexual relations between parents and children or involving certain authority figures, such as teachers or ministers of worship – to remain in force[66][21] The ruling came into effect two days later with its publication in the Official Gazette.