Deep-sea fish

[3] It has been speculated that deep-sea ecosystems may have been inhospitable to vertebrate life prior to an increased influx of nutrients into the ocean during the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous following the rise of angiosperms on land, which led to an increase in abyssal invertebrate life, allowing fish to in turn colonize these ecosystems.

[4][5] The earliest known records of deep-sea fish are trace fossils of feeding and swimming behavior attributed to unidentified neoteleosts (referable to the ichnogenera Piscichnus and Undichna), from the Early Cretaceous (130 million-year-old) Palombini Shale of Italy, which is thought to have been deposited in the abyssal plain of the former Piemont-Liguria Ocean.

Prior to the discovery of these fossils, there was no evidence for deep-sea bony fish older than 50 million years in the Paleogene.

[10][11] Notable Neogene formations that preserve fossils of deep-sea bony fish are known from the Miocene of Italy, Japan, and California.

Marine snow includes dead or dying plankton, protists (diatoms), fecal matter, sand, soot and other inorganic dust.

However, most organic components of marine snow are consumed by microbes, zooplankton and other filter-feeding animals within the first 1,000 metres (3,281 ft) of their journey, that is, within the epipelagic zone.

Some deep-sea pelagic groups, such as the lanternfish, ridgehead, marine hatchetfish, and lightfish families, are sometimes termed pseudoceanic because, rather than having an even distribution in open water, they occur in significantly higher abundances around structural oases, notably seamounts and over continental slopes.

David Wharton, author of Life at the Limits: Organisms in Extreme Environments, notes "Biochemical reactions are accompanied by changes in volume.

Most fish that have evolved in this harsh environment are not capable of surviving in laboratory conditions, and attempts to keep them in captivity have led to their deaths.

Many of these organisms are blind and rely on their other senses, such as sensitivities to changes in local pressure and smell, to catch their food and avoid being caught.

The ability to produce light only requires 1% of the organism's energy and has many purposes: It is used to search for food and attract prey, like the anglerfish; claim territory through patrol; communicate and find a mate, and distract or temporarily blind predators to escape.

[22] The lifecycle of deep-sea fish can be exclusively deep-water, although some species are born in shallower water and sink upon maturation.

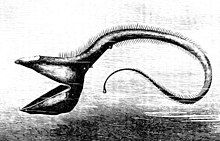

The deep-sea angler fish in particular has a long fishing-rod-like adaptation protruding from its face, on the end of which is a bioluminescent piece of skin that wriggles like a worm to lure its prey.

Great sharp teeth, hinged jaws, disproportionately large mouths, and expandable bodies are a few of the characteristics that deep-sea fishes have for this purpose.

Groups of coexisting species within each zone all seem to operate in similar ways, such as the small mesopelagic vertically migrating plankton-feeders, the bathypelagic anglerfishes, and the deep-water benthic rattails.

This turned out to be due to millions of marine organisms, most particularly small mesopelagic fish, with swim bladders that reflected the sonar.

[28] The swim bladder is inflated when the fish wants to move up, and, given the high pressures in the messoplegic zone, this requires significant energy.

[38] These fish have muscular bodies, ossified bones, scales, well developed gills and central nervous systems, and large hearts and kidneys.

[39] The brownsnout spookfish, a species of barreleye, is the only vertebrate known to employ a mirror, as opposed to a lens, to focus an image in its eyes.

[42] Indeed, lanternfish are among the most widely distributed, populous, and diverse of all vertebrates, playing an important ecological role as prey for larger organisms.

The estimated global biomass of lanternfish is 550–660 million tonnes, several times the entire world fisheries catch.

Conditions are somewhat uniform throughout these zones; the darkness is complete, the pressure is crushing, and temperatures, nutrients and dissolved oxygen levels are all low.

[15] Bathypelagic fish have special adaptations to cope with these conditions – they have slow metabolisms and unspecialized diets, being willing to eat anything that comes along.

What little energy is available in the bathypelagic zone filters from above in the form of detritus, faecal material, and the occasional invertebrate or mesopelagic fish.

[56] Despite their ferocious appearance, these forms are mostly miniature fish with weak muscles, and are too small to represent any threat to humans.

[64] Deep-sea organisms possess adaptations at cellular and physiological levels that allow them to survive in environments of great pressure.

Ten orders, thirteen families and about 200 known species of deep-sea fish have evolved a gelatinous layer below the skin or around the spine, which is used for buoyancy, low-cost growth and to increase swimming efficiency by reducing drag.

[42] Indeed, lanternfish are among the most widely distributed, populous, and diverse of all vertebrates, playing an important ecological role as prey for larger organisms.

In the Southern Ocean, Myctophids provide an alternative food resource to krill for predators such as squid and the king penguin.

Although these fish are plentiful and prolific, currently only a few commercial lanternfish fisheries exist: these include limited operations off South Africa, in the sub-Antarctic, and in the Gulf of Oman.