Definition of planet

Greek astronomers employed the term ἀστέρες πλανῆται (asteres planetai), 'wandering stars', for star-like objects which apparently moved over the sky.

As the 19th-century German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt noted in his work Cosmos, Of the seven cosmical bodies which, by their continually varying relative positions and distances apart, have ever since the remotest antiquity been distinguished from the "unwandering orbs" of the heaven of the "fixed stars", which to all sensible appearance preserve their relative positions and distances unchanged, five only—Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn—wear the appearance of stars—"cinque stellas errantes"—while the Sun and Moon, from the size of their disks, their importance to man, and the place assigned to them in mythological systems, were classed apart.

[6] In his Phaenomena, which set to verse an astronomical treatise written by the philosopher Eudoxus in roughly 350 BCE,[7] the poet Aratus describes "those five other orbs, that intermingle with [the constellations] and wheel wandering on every side of the twelve figures of the Zodiac.

"[10] Marcus Manilius, a Latin writer who lived during the time of Caesar Augustus and whose poem Astronomica is considered one of the principal texts for modern astrology, says, "Now the dodecatemory is divided into five parts, for so many are the stars called wanderers which with passing brightness shine in heaven.

As the historian of science Thomas Kuhn noted in his book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions:[20] The Copernicans who denied its traditional title 'planet' to the sun ... were changing the meaning of 'planet' so that it would continue to make useful distinctions in a world where all celestial bodies ... were seen differently from the way they had been seen before...

[28] However, when the "Journal de Scavans" reported Cassini's discovery of two new Saturnian moons (Dione and Tethys) in 1686, it referred to them strictly as "satellites", though sometimes Saturn as the "primary planet".

[32] One of the unexpected results of William Herschel's discovery of Uranus was that it appeared to validate Bode's law, a mathematical function which generates the size of the semimajor axis of planetary orbits.

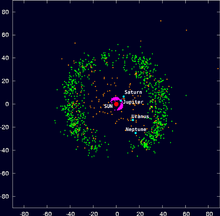

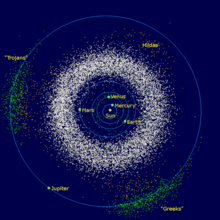

Since Bode's law also predicted a body between Mars and Jupiter that at that point had not been observed, astronomers turned their attention to that region in the hope that it might be vindicated again.

Herschel suggested that these four worlds be given their own separate classification, asteroids (meaning "starlike" since they were too small for their disks to resolve and thus resembled stars), though most astronomers preferred to refer to them as planets.

[37] The long road from planethood to reconsideration undergone by Ceres is mirrored in the story of Pluto, which was named a planet soon after its discovery by Clyde Tombaugh in 1930.

None of these applied to Pluto, a tiny and icy world in a region of gas giants with an orbit that carried it high above the ecliptic and even inside that of Neptune.

On June 11, 2008, the IAU executive committee announced the establishment of a subclass of dwarf planets comprising the aforementioned "new category of trans-Neptunian objects" to which Pluto is a prototype.

To date, only two other TNOs, 2003 EL61 and 2005 FY9, have met the absolute magnitude requirement, while other possible dwarf planets, such as Sedna, Orcus and Quaoar, were named by the minor-planet committee alone.

[59] Among the most vocal proponents of the IAU's decided definition are Mike Brown, the discoverer of Eris; Steven Soter, professor of astrophysics at the American Museum of Natural History; and Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of the Hayden Planetarium.

In an article in the January 2007 issue of Scientific American, Soter cited the definition's incorporation of current theories of the formation and evolution of the Solar System; that as the earliest protoplanets emerged from the swirling dust of the protoplanetary disc, some bodies "won" the initial competition for limited material and, as they grew, their increased gravity meant that they accumulated more material, and thus grew larger, eventually outstripping the other bodies in the Solar System by a very wide margin.

A number of Pluto-as-planet proponents, in particular Alan Stern, head of NASA's New Horizons mission to Pluto, have circulated a petition among astronomers to alter the definition.

Mark Sykes, director of the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona, and organiser of the petition, expressed this opinion to National Public Radio.

[67] Brown notes, however, that were the "clearing the neighbourhood" criterion to be abandoned, the number of planets in the Solar System could rise from eight to more than 50, with hundreds more potentially to be discovered.

[68] The IAU's definition mandates that planets be large enough for their own gravity to form them into a state of hydrostatic equilibrium; this means that they will reach a round, ellipsoidal shape.

Many are spheroids, and several, such as the larger moons of Saturn and the dwarf planet Haumea, have been further distorted into ellipsoids by rapid rotation or tidal forces, but still in hydrostatic equilibrium.

In addition, the much larger Iapetus is ellipsoidal but does not have the dimensions expected for its current speed of rotation, indicating that it was once in hydrostatic equilibrium but no longer is,[70] and the same is true for Earth's moon.

[76][77][78] Indeed, Mike Brown makes just such a claim in his dissection of the issue, saying:[63] It is hard to make a consistent argument that a 400 km iceball should count as a planet because it might have interesting geology, while a 5000 km satellite with a massive atmosphere, methane lakes, and dramatic storms [Titan] shouldn't be put into the same category, whatever you call it.However, he goes on to say that, "For most people, considering round satellites (including our Moon) 'planets' violates the idea of what a planet is.

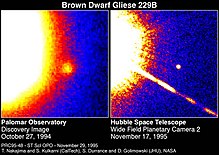

However, due to the relative rarity of that isotope, this process lasts only a tiny fraction of the star's lifetime, and hence most brown dwarfs would have ceased fusion long before their discovery.

Indeed, astronomer Adam Burrows of the University of Arizona claims that "from the theoretical perspective, however different their modes of formation, extrasolar giant planets and brown dwarfs are essentially the same".

However, the current convention among astronomers is that any object massive enough to have possessed the capability to sustain atomic fusion during its lifetime and that is not a black hole should be considered a star.

Further, in 2010, a paper published by Burrows, David S. Spiegel and John A. Milsom called into question the 13-Jupiter-mass criterion, showing that a brown dwarf of three times solar metallicity could fuse deuterium at as low as 11 Jupiter masses.

[96] The Exoplanet Data Explorer includes objects up to 24 Jupiter masses with the advisory: "The 13 Jupiter-mass distinction by the IAU Working Group is physically unmotivated for planets with rocky cores, and observationally problematic due to the sin i ambiguity.

[102] The ambiguity inherent in the IAU's definition was highlighted in December 2005, when the Spitzer Space Telescope observed Cha 110913-773444 (above), only eight times Jupiter's mass with what appears to be the beginnings of its own planetary system.

[103] In September 2006, the Hubble Space Telescope imaged CHXR 73 b (left), an object orbiting a young companion star at a distance of roughly 200 AU.

[106] In 2019, astronomers at the Calar Alto Observatory in Spain identified GJ3512b, a gas giant about half the mass of Jupiter orbiting around the red dwarf star GJ3512 in 204 days.